A labyrinth is a symbolic journey…but it is a map we can really walk on, blurring the difference between map and world.” – Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking

Incongruously, in a place known mainly for its outdoor, oddball and vigorous physical activity – winter and summer – we found a labyrinth on a hillside site designed to encourage meditation, introspection and mental well-being.

During our visit to Otepaa, near the Latvian border of Estonia, we did two wonderful 15 kilometer hikes, despite cold and drismal weather. One day we circled the large lake here, Puhajarve, or the Holy Lake. It had been blessed in the past by the Dalai Lama. The next day we traipsed uphill and down on a serenely wooded forest trail at Kaariku, a challenging Nordic skiing track in winter.

But a labyrinth was something else. Even the location was odd, on one side of a busy main road near the center of Otepaa. The town’s main church, the 19th century St. Mary’s Lutheran, looms over the road and over the town from atop the same hill. Because it’s unheated, St. Mary’s remains closed during the winter months, including April when we visited. Parishioners seeking solace use the “winter church” instead.

Finding the huge church is easy no matter where you are in town, but only a small wooden sign in the church’s parking area marked where to find the labyrinth downhill across the road. We searched for a bit before we found it.

Part of the confusion is that we could only see a diminutive parking lot from the road, one that actually looked private because it’s near a small house. As we walked downhill past the house, a man parked briefly and secured a for sale sign on the house’s picket fence.

About twenty paces down from the house, we could finally see an explanatory sign – as well as the labyrinth itself, placed along the hillside in a space 11 meters square. On the sign, we read how some local people – presumably looking for more than the physical pleasures of the area – created this place for inward activity. This site had apparently been a holy grove in the past, and emitted strong energy from the earth.

The energy of the place apparently flows downhill farther. We noticed what appeared to be a community garden toward the base of the hill, with a number of plots ready for planting. Alongside these was an improvised sculpture garden arranged from cast-off items. From the hillside across from the gardens, we could hear the clamor of unseen children at play.

The sign proposed detailed instructions to follow. To start, we were to approach the labyrinth individually through an arched canopy of vines. We would knock on a board hanging from the canopy, and utter the suggested incantation for well-being, “I am healthy; I am well.”

Then, after walking thru the canopy, we were to start to the left of the labyrinth. There we would step through a small counter-clockwise “golden” spiral, its path marked by irregular stones roughly 20 – 25 cm in size. That was to clear our minds and prepare for the main event, doing the labyrinth.

Then, after winding through the half kilometer pathway of the labyrinth, we were to head to an actual teepee adjacent to it. The teepee was made of long sticks leaning against each other in a spiraling conical shape. Inside we were to sit on benches facing a central arrangement of candles and glass jars, channeling energy through the cone – a place for reflection and letting the lessons of the labyrinth settle in.

To finish, we would pass back through the entry canopy.

Now it was time for us to play. Oddly, despite the intent of the spiral, our minds were anything but clear there; instead, they seemed full of one troubling problem or another.

After the spiral, one at a time, we turned to the labyrinth’s entrance.

The centre that I cannot find

Is known to my unconscious Mind;

I have no reason to despair

Because I am already there.

– W.H. Auden, The Labyrinth

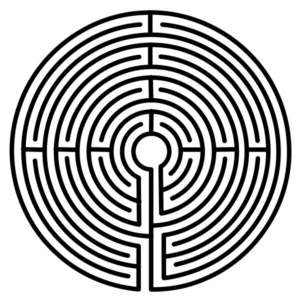

Unlike a maze in which one tries to avoid getting lost, a labyrinth is a way of finding oneself, a set path along which one can gain insight or calm. It’s a form of ritual, akin to the Asian mandala. Both are two-dimensional representations of a three dimensional climb to enlightenment, where earth energy and cosmic energy are said to meet. The western labyrinth is a circle that winds inward to a central point; because you physically walk it, you then unwind back out to the world. The mandala, by contrast, is typically a symbolic approach to Mt. Meru, with spiritual nirvana at the central peak…but no unwinding. Yet physical representations of a mandala, such as the Borobodur temple in Jogjakarta, Indonesia, are actual climbs from which you must return – before closing hours.

The circular labyrinth at Otepaa was modeled on the famous Christian labyrinth etched onto the paved stone floor of Chartres Cathedral in France. That one was derived from other medieval labyrinths, whose history hearkens back to the Greeks. When they let you do the labyrinth at Chartres, you can actually walk the path etched onto the floor. We were there once when the thing was covered with chairs and roped off.

As at Chartres, the Otepaa labyrinth consisted of eleven circles marked off in this same pattern, both symmetrical and quite beautifully designed. Unlike Chartres, however, this one was aslant on the hill. Its lines were defined by carefully placed stones 20 to 25 cm in size, and the path itself was rough, an uneven surface of small broken stones spread between the lines.

What did we find as we made the 10 minute walk through the labyrinth? We actually did start to see the problems that beset us more clearly and felt a calmness about them, a calmness that came with sensing how the problems could be resolved.

And we learned a few other things about dealing with troubles, about dealing with life. Two of them are implicit in the Chartres design:

- First, as you walk, you often find yourself close to the center but not quite there. The lesson: you don’t achieve your goal as readily as it you might hope. You must run a full course.

- Second, there’s no mystery about the labyrinth as you can see the whole thing and you know you will reach the center. But how the route leads to the center is puzzling. Even while we were walking it, we couldn’t figure out how it could work. The lesson? Resolution or insight is perhaps always possible if you commit to a path, however wayward or uncertain it might seem.

Two more lessons seemed unique to the Otepaa labyrinth:

- Staying balanced along the way was often difficult. Those broken pieces of stone on the path often made walking steadily a challenge. So, it can be difficult to maintain one’s balance in dealing with the troubles life sends you; you need to concentrate to keep your footing at times,.

- Second, at the lower end of the hill, the path narrowed to half the width of the path in the uphill half. Stepping through the narrow part challenged us to stay within the path, forcing us to re-focus on the effort. Resolution and insight, it appears, follows some easy patches, but requires tough ones as well.

Nancy had gone first through the labyrinth, but waited at the central cairn of rocks for Barry to join her. We had both felt the short, calming mindfulness of the labyrinthine journey. We had seen how we could take its lessons away with us.

We then finished the procedure, reversing our steps in the labyrinth, stopping in the teepee and heading back thru the canopy.

But those steps hardly seemed necessary. For, at the center, we kissed, then unwound our path together back into the world.

(Also, for more pictures from Estonia and the Baltics, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the Baltics itinerary page.)