In brief: Two hundred years ago war left its traces in the middle of Portugal, where now domestication and natural calm prevail.

Linhas de Torres – the Lines of Forts

Most know that the Russian front prevented Napoleon’s advance in the War of 1812. Yet few of us know that Portuguese-British forces stopped Napoleon’s advance during the Peninsular War of 1810 – 1814 with a clever array of fortifications north of Lisbon.

Little is left to see of the three Linhas de Torres (Lines of Towers) designed by Wellington, which stretched from the Tagus River to the Atlantic Ocean. It’s a peaceful, domesticated land today, with the hilly landscape filled with apartments and houses as well.

During wartime, however, the defenders along the line not only built the fortifications but razed the landscape as well. That scorched earth approach deprived Napoleonic forces of any shelter, food, or other resources.

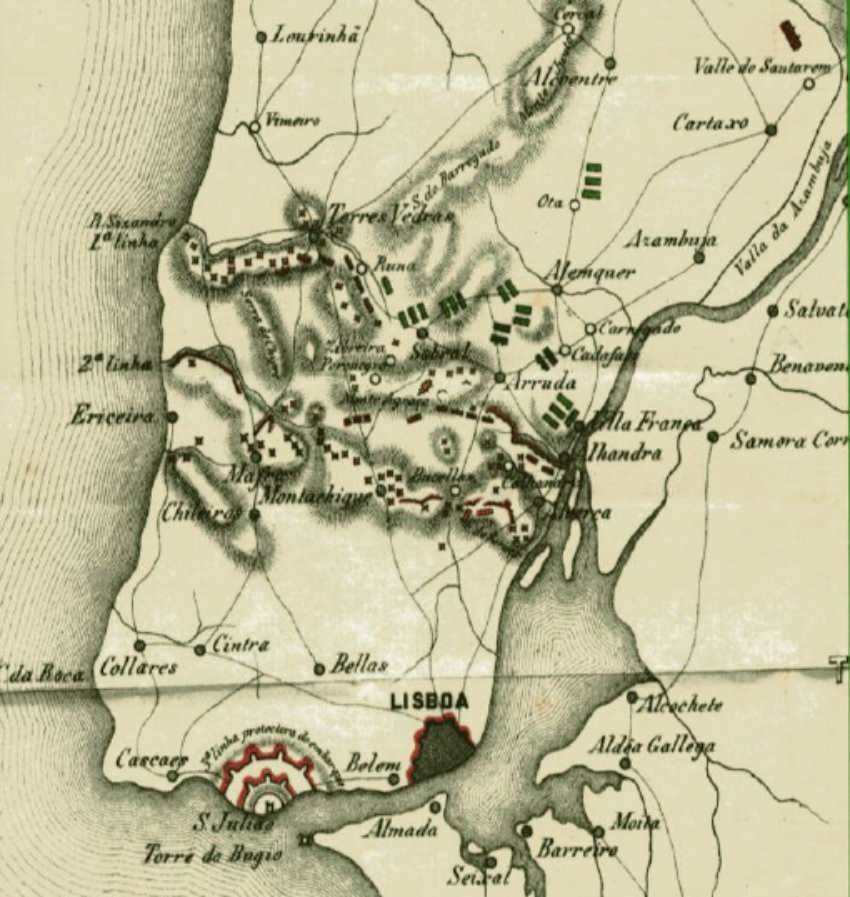

As shown on this old map, the three lines extended 85 km (53 miles) atop the natural hilly landscape. And they accommodated over 6000 defending soldiers, 100 cannons, 152 forts constructed within just a few years (the black rectangles), as well as 14 gunboats to complete the line across the narrowing Tagus River at Vila Franca.

And we learned, while driving among the lines on our recent trip, they worked.

We got a better feel for why when we visited the imposing Hercules column memorializing the heroic defense against Napoleon.

The monument above Vila Franca dates from 1874, 60 years after the victory, with Hercules representing strength, bravery and a few more virtues, despite wearing only a fig leaf.

He watches stolidly over the Tagus River on a site of a major fortification and control point for the Lines of Towers. The defensive forces needed to ensure that French troops could not use the narrow parts of the river here to bypass the lines. So the armed ships were critical to Wellington’s strategy.

Inland, in the middle of Wellington’s lead defensive line, the old town of Torres Vedras is as quiet as the rest of the landscape now. Nor was this tower ever involved in the Napoleonic wars. It’s a 15th century castle and royal palace, destroyed by natural forces during the huge 1755 earthquake and restored long after peace broke out on the peninsula.

Buçaco: Spiritual and physical battles

Everyone we met near Coimbra said we needed to go to Buçaco National Forest for the tranquil beauty of its ancient woods and extensive walks. During the exquisite day of our visit we found they were right. And discovered how it has been a place of contrasts between the contemplative and the militaristic, between the wild and the cultivated.

For hundreds of years there had been two convents at Buçaco gathering dedicated adherents within its woods and excluding all but contemplative pilgrims.

One of the two convents remains, the Convento de Santa Cruz, converted into a museum of religious practice by the nuns.

The charming altar of the church at Convento de Santa Cruz.

Within the convent, we could still see the old hallways, chapel and residential cells. Oddly, all the doors, decorative elements and ceilings had been constructed from cork. At each turning point of the hallways, as here, a simple oratory served for a moment of prayer.

During the defense of Portugal against Napoleon, however, the Duke of Wellington stayed at one of the convents, and used the advantage of the heights around them to conduct and win the crucial Battle of Buçaco against the French troops.

In 1810, this vantage point served the Duke of Wellington well, while he nestled his troops protectively on the inner slope of the mountain.

Today, the view contrasts dramatically with the modernized, cultivated landscape surrounding the old woods of Buçaco. And, ironically, the viewpoint is Cruz Alta, the summit of the Via Sacra, a steep pilgrimage for meditating on Christ’s path to crucifixion as one climbs to the celestial perspective.

In the backdrop here is the hillside of the Via Sacra, where the Duke arrayed his troops. This view is from the rooftop of the Convent museum reached by climbing the narrow winding stair of the bell tower. Near at hand is a bird’s eye view of the palace to the left and its formal garden, which supplanted the second convent in the late 19th century.

The faux-Manueline Renaissance palace, which is now a starry hotel, shows off its tower on the right. On the left, is the simple stonework-decorated convent building that remains.

Imitation or not, the fanciful style of the palace can be quite impressive. Visitors are discouraged from entering the hotel.

In the same period that the palace replaced the convent, some of the forested land was adapted into park-like elements. This 19th century pathway, for example, skirts a little stream and heads toward the Great Pond past a staircase with the Fonte Fria (Cold Fountain). This is one of countless pathways winding through Buçaco.

Despite these more formal park elements, the contrast of the thick forest of Buçaco with the surrounding landscape, denuded for agriculture, shocked us at the high vantage points. Indeed, the huge trees in its centuries-old forest feature in their own posted walk.

Once again up high near the top of the Via Sacra, we could look back at the secular palace and sacred convent. The landscape beyond shows how different this 100-plus hectares of wooded refuge still is.

Fortunately, both the convent’s sacred interests and the palace owner’s secular ones had combined to preserve this refuge over time. And, during the last 100 years, the country wisely kept Buçaco’s both wild and cultivated features as a public, rather than religious, refuge from the day-to-day world.

Along the Via Sacra, a setting for religious meditation

Each in a series of small buildings like this one along the Via Sacra climb contain a station of the cross. They encouraged pilgrims to meditate on the progress of Christ to his death.

Within the building, viewed through an often murky window, is a life-sized clay representation of one of the stations of the cross, some of which were strangely damaged, with faces of auxiliary characters broken. In this one, Veronica offers her scarf to wipe Jesus’ face, whose image was then imprinted on the cloth.

Still nearly hidden in the woods, this rough stone hermitage reminded us of the original purpose of Buçaco, quiet retreat from the world for spiritual growth. The building was in good enough shape for us to enter somewhat bent over, and view a few small rooms outfitted with stony prayer niches. Outside its farther door, however, we found that splendid viewpoint overlooking the convent and castle and surrounding landscape.

A newer “high cross” – Cruz Alta – tops the summit of the Via Sacra. We’re not sure how many pilgrims still do this walk, or feel the religious spirit, but the few tourists we saw were mostly interested in the pleasure of photo ops – and the 360 degree view.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Portugal, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)