We were fortunate to visit many tribal villages across Senegal, especially in the desert and dry savannah areas of the country before the rains. In them, we met with chieftains, elders male and female, as well as the young – all of whom were pleased that we could visit their homes and explain their culture to us – initiation rites, marriage practices, the ruling structures, the seasonality of work, and some of their typical foods.

Fulani People of the Desert

The Fulani people are Muslim tribes of the desert, who live off cattle and goats, selling the milk and meat for other needs. Their villages are mostly small – family communities really. Their stock roams freely during the dry months and is gathered again after the rainy season when the grasses grow plentifully.

We were told proudly that the Fulani tribe has produced a surprising number of leaders in various countries across Africa, including Senegal.

These young Fulani are members of a nomadic group, whose gear was loaded onto several carts. Many of the Fulani tribe remain nomadic, shifting periodically from place to place for the most advantageous grazing of their animals. Most, however, stay in permanent villages.

When we arrived, the group was listening to music while awaiting other tribal members. After introductions, we joked about dancing to the music as the young man handed the player to Nancy. Soon everyone broke into an informal tribal dance that the girl on the far right just had to record on her phone. TikTok?

These children drive their donkey cart around to deliver ice to the Fulani villages, like the one with thatched huts in the background. Most of the men were tending the cattle, so we met with the women who were doing chores and preparing meals.

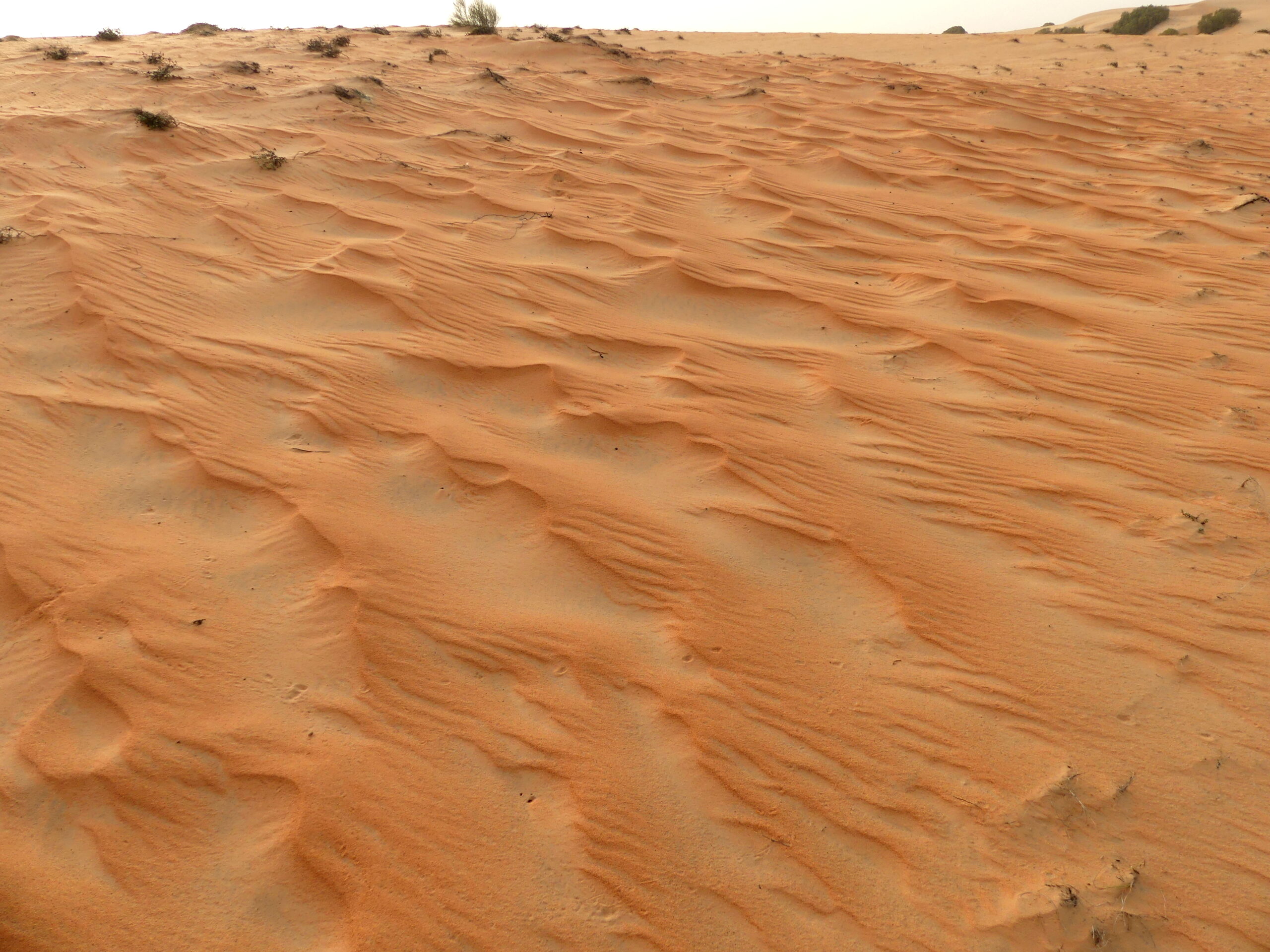

A bit of the Sahara around Lompoule. Beautiful as this is, Senegal and the countries of the Sahel to the east fret about the drift of the Sahara southward to encroach on the fertile lands of the sub-Sahara. So a joint initiative among those countries is to develop a green wall of sorts, as a barrier to the desert, for the benefit of its diverse animal population and the growing human one.

Desert beauty between Dakar and Saint-Louis, at Lompoule. We were reminded of the Saharan Erg of Algeria and other vast deserts we had visited.

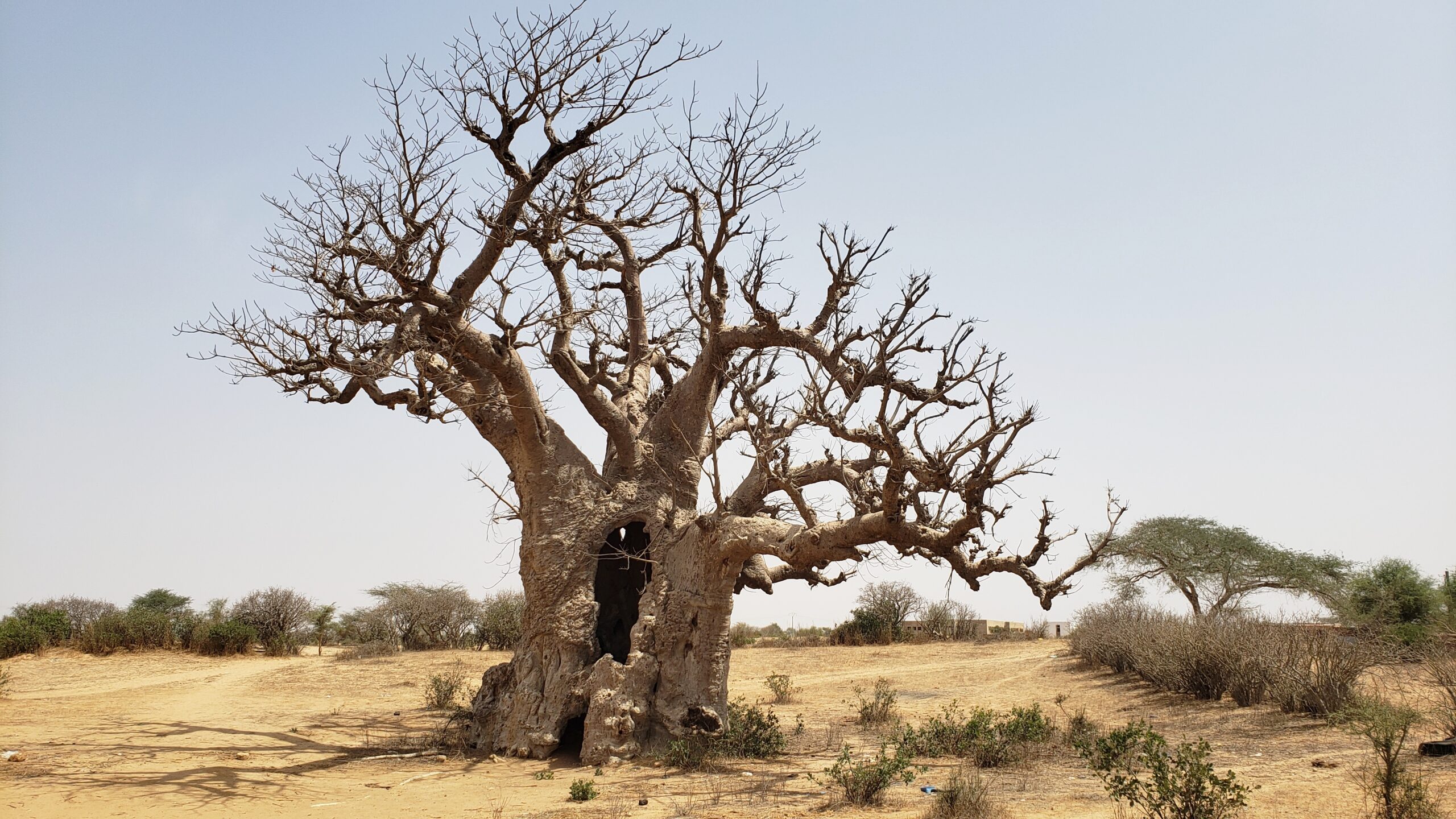

A giant baobab in arid Senegal. As is common with older baobab trees, this one was hollow enough to walk into and peer out. The baobabs were often revered by animist tribes, who buried their griots, or prophetic story tellers, in the hollows.

The Mouride City of Touba

Touba (or Felicity, in Arabic), the second largest city in Senegal, now contains over a half-million people, all believers in one holy man.

Ahmadou Bamba Mbacke was a Sufi religious leader and founder here of the Mouride brotherhood, which spread widely. His teachings reflected his emphasis on peacefulness, work, and mastery of oneself. His peaceful resistance to colonial rule further spread his reputation. For that, however, he was exiled or sequestered by the French for decades. When he was allowed to return, his followers gathered with him in the desert city of Touba, soon attracting many others. After he died in 1927, his sons, the hereditary heirs to his movement, continued his work, building this mosque for prayer, learning, and community support.

This is the Grand Mosque of Mouridism in Touba. For a sense of scale, notice the robed figures at the lower edge.

An outer hall for prayer at the Grand Mosque. This is one of many similar spaces to accommodate the faithful, who may pray, meditate, or rest as they wish. Within the mosque, a community kitchen serves meals free to those who are hungry. And a hospital caters to physical ailments.

A glorious passageway to the mosque’s inner prayer halls, open only to Muslims. The founder of Mouridism is buried within, and the two sons who succeeded him as heads of the faith are buried in mausoleums to the side of the main building.

Senegalese typically seek out a spiritual leader to guide their practice of Islam. Everywhere, you see the names marked in tribute on buildings, offices, trucks, boats, etc.

Bassari Country – the Bedik, Serer, and Pula

UNESCO has recognized the Pays Bassari, in the dry plains of southeastern Senegal, for its cultural heritage.

Part of the landscape of Pays Bassari. Atop this mountain is the Bedik village we visited, with a wide perspective over the landscape.

Here, the Bedik and, below them, the neighboring Serer and Pula tribes of this area, have maintained their ages-old style of living, sustaining a harmony with the land, and holding to their traditional beliefs.

To us, the Bedik village turned out to be the most interesting of these visits.

“What is most important to know about the Bedik people?” we asked. We were sitting on various large stones that felt oddly formal, together with the chief of the tribe and his “court.” To the left in our photo, the chief sits amid that shaded array of stones.

We had just climbed to their village on the rocky outcrop and been escorted to the leaders’ site. Though the Bedik like their villages up high, they live peaceably with the other tribes down on the plains.

The chief’s brothers continually weaved basketry during our discussion, using the time profitably. During dry season, when there is little to do for agriculture, the villagers produce beaded jewelry as well as goods like this for sale in town.

In response to our question, the chief proudly spoke of their independence, how they had left Islamic Mali and resisted Christian influences to remain animist in their religious beliefs. They also talked of their governance. A conference of village elders decides on the successor, passing leadership to a different village family when the time comes.

After our visit with the leaders, several young men guided us along the tiny, dusty streets. We greeted some older women along the way and others at work.

A view over the thatched rooves and round clay houses of the Bedik village, divided into sections by families. Their life is often hard, but all the villagers we met projected an enviable contentment.

During our visit, we encountered a French man at one house who felt the same. He had ventured into the village during the lush rainy season some years before and liked the community so much that he built a typical round house and stayed.

This Bedik woman is finishing a clay pot by hitting it firmly with a flat stone. The different tribes of the area largely survive as shepherds and farmers of crops like peanuts. This dry season is their quiet time, so other work like making pots becomes important.

In this season also, many of the villagers move to the large towns for seasonal work. While walking through the village, we found those remaining in the village to be very welcoming and gracious. Some offered us gifts of fruit; others a bag of those delicious peanuts they harvest.

Serer and Pula Villages

In these villages also, many had departed to the larger towns for seasonal work and selling.

When we arrived at the entrance of one Bassari village, an older woman was supervising the gathering of mangoes off a large tree with a long forked stick. We were terrible at the task. Then her grandson showed off his own technique by climbing up instead. We think he ate more than he returned with.

The houses of the Bassari villagers in the plains typically had roofed terraces outside their round houses. There they would work, greet others, or even sleep in the cooler air. After a bit of talk on the veranda, we were invited into this one by a mother and daughter so we could get a feel for their simple, but sufficient accommodations. Though they often sit on mats or short stools, we were graciously invited to use the only furniture, their beds.

Every day is washing day on this river in Bassari country, even in the dry season. The women here rinse the clothing in the water and slap it on the rocks. Nearby some villagers were using shallow pans to sift the stream for gold; others panned in round holes dug down a meter or two in the river shoals.

The villagers send their children into town for early education. Most continue to the upper grades in the nearest cities. This is a class in a school for over 700 village youngsters, evenly divided between boys and girls. It might look crowded, but the students are clearly learning math, French and Arabic, as well as other topics.

They were eager to write their names on their slates for us and very orderly even with our disruption. When asked to sing the Senegalese national anthem, they rivalled any chorus. In thanks, we left a gift of a soccer ball and pencils, as well as a donation to the head of the school for other materials.

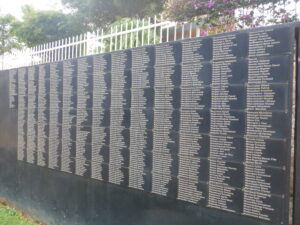

Villagers of Another Time: Stone Circles of Senegambia

Along much of the Gambia River, and its encasing country of The Gambia, the landscape contains a unique concentration of burial sites marked by hundreds and hundreds of mini-Stonehenges, stone circles up to 2000 years old. It’s no wonder that these sites have been given World Heritage status. The sites – now split between The Gambia and Senegal – were built by tribes which even today occupy both countries.

We visited the largest of these Senegambian clusters at Sine Ngayene in Senegal, with over 50 circles visible and over 1100 stones, weighing up to seven tons each. We explored them with the local guardian, whose father had assisted the original archeological teams over 20 years ago.

The stones vary greatly in size and you can’t see the buried part, but many are quite large.

The stones are laterite, an iron-rich rock that was mined quite a distance away. We guessed that many had been knocked over by shifting ground or other people. Yet, a large part of each stone is below ground, buried to provide stability. The current guardian said that lightning strikes – attracted by the iron in the rock – toppled and cracked the stones. But we weren’t so sure about that explanation.

The burial sites were sacred for the tribes when they were constructed, and the people seemed to live close by. According to the guardian of the site, the villagers still consider it hallowed in a way and would never harm it. However, we had to share the site with a group of goats. But we realized that they perform a useful function, chewing down the dry grasses that might catch fire.

This site is special due to the great number of stone circles, but also the presence of the double circle below, with one ring of stones inside another ring. The builders must have considered it important because it was placed at the crux of three branches of circular tombs in a Y-formation. Archeologists found evidence that this marks a double burial, of a king and a queen.

Each stone circle had a portal to its east marked by two stones, a symbolic doorway. This was one of the most evident examples.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Senegal, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)