The World Heritage hilltop city of Toledo, our last stay during our trip to Spain, was long a capital:

- for the Visigoths, who succeeded the Romans;

- for the Umayyad Muslims who overran Spain;

- for the Royal Court of the Holy Roman Empire in Spain;

- and for the Catholic church in Spain.

Toledo’s wealth ensured grand imperial projects and religious structures, still here to see. But, by the 16th century, Madrid usurped much of its importance and further decline resulted from the conflict with Napoleon.

To us, the antiquities were impressive, but we were most impressed with a less obvious historical value. During its dominance in the Middle Ages, Toledo thrived as the “City of Three Cultures,” whose narrow lanes bustled with Muslims, Jews and Christians. That city flourished with creative interchange until religious intolerance sadly closed it down.

The Cathedral

Even before intolerance peaked, the Catholic religion dominated Toledo. And its primary emblem was the Cathedral.

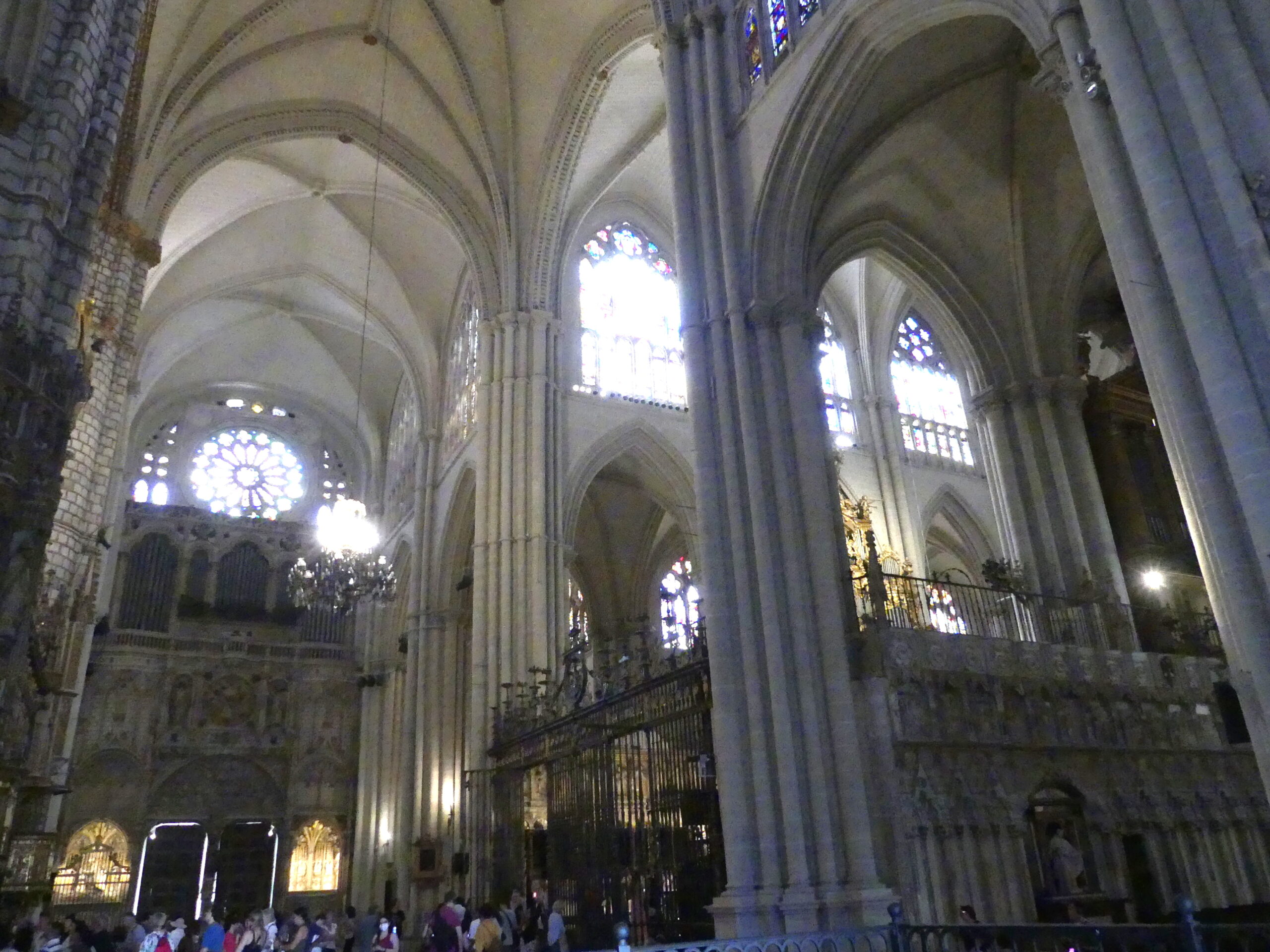

The vaulting interior of the 13th century Gothic Cathedral makes all below seem small or insignificant. Modeled on Bourges in France, it is typically considered the most magnificent in Spain, not just in itself but for the myriad works of art installed within it across the centuries. One French historian called it a world in itself.

The art includes the stained glass windows not quite visible in the photo due to the dark interior, but mostly dating from the a few centuries after construction began.

You could spend hours there just meditating on this grand Gothic altarpiece, or retable, which retells the life of Jesus in polychrome scenes separated by intricate decoration, as well as the stone statuary climbing the five-story high walls and columns to the sides.

The Sacristy of the Cathedral houses a treasure trove of artworks, including El Greco’s altarpiece in the center with his elaborate and celebrated 16th century painting of the Disrobing of Christ. El Greco lived 37 years in Toledo until his death. Other works of his accompany this one in the room (though most of the casual visitors seemed to ignore them). Nearby are works by Bellini, Raphael, Caravaggio, Goya, Titian and other Spanish masters. The baroque ceiling almost steals the show from the painting riches.

We joined a coterie of nuns to admire the stunning 15th century Renaissance stalls of the Cathedral’s choir. The lower stalls, which look bronzed in the photo, consist of panels that detail the story of the conquest of Granada against the Moors. The upper stalls, topped by Biblical figures and saints, would seat the most important church officials. Two sets of organ pipes reach out above the seats, while the central aisle of the church and its rose window hover overhead.

Jewish and Moorish Toledo

This is one of two synagogues in the Jewish Quarter that survived the collapse of religious amity and were converted to churches. This mesmerizing carved stone wall in the del Tránsito synagogue, now the museum of Jewish culture here before the exile, was the location for the ark to hold the Torah. Psalms and other Biblical excerpts etched in stone accompany the design.

We were dazzled by the interior of the 12th century Ibn Shoshan synagogue in the Jewish Quarter, with five naves of bright white columns topped by a variety of gilded capitals, rows of large, graceful arches supporting complex Mudejar designs, and a set of Moorish archways above. It’s reputedly the oldest remaining synagogue in Europe, but it became the Santa Maria La Blanca church after Jews were exiled from Spain.

We only located one mosque, on the other side of town, near the ancient portals. It too was converted into a church, but the brick exterior decorated with arches, cylindrical walls, and tower still stand.

The City

This map of the walled city of Toledo by El Greco in the early 1600s, as seen from the Tagus River, can still guide you around town, with some exceptions. It hides the medieval parts like the Gothic Cathedral considered out-of-date, yet heralds the city’s Roman past by including the river god with the Tagus, as well as Toledo’s divine blessing, with Mary afloat on the heavens.

The walls that began with the Romans, Visigoths, and Moors still encircle Toledo today. We could walk around the base, craning our necks to see the top rising over 10 meters (30 feet), where there is no walkway. There are many gateways to enter, however.

This Gate of King Alfonso VI was once the main gate. Its charm, we thought, lay in the varied types of stonework, the 9th century Moorish arches, the crenellated fort at the back of it – and the stunned expression of the face within the central arch.

It’s not perhaps as impressive in a way as is the later, weightier Bisagra Gate nearby, whose stalwart twin turrets are joined by an archway featuring a huge double headed eagle.

A Jesuit church stands on one of the highest points of Toledo, with an inviting tower to climb to enjoy this panorama of the hilltop. The main façade of the Cathedral is visible to the right of its great tower, a dominant presence though lower than we were.

The other notable structure visible across the tiled roofs is the Alcázar, or fortress building, visible in El Greco’s 17th century map of the city. Though dating originally from the Roman era, the fort was completely rebuilt in the 20th century after the Spanish Civil War. Also to the right are the neighboring hills across the Tagus River and, in the distance, the river itself.

Looking west from a park at the edge of the Jewish Quarter and high over the Tagus River, we thought we shifted back in time to a landscape little changed since the Romans. We also felt a kinship with the river for it continues onto Lisbon as its major river, the Tejo.

The buildings in the center of Toledo might have been renovated, but the narrow streets are the same as those used in the Middle Ages, weaving up and down the hilltop.

Toledo is quite charming at night, with all the ancient stone structures lit up.

Below is a tower of the 15th century Monastery of San Juan de los Reyes which usurped a large part of the Jewish Quarter then.

The structure ordered by Queen Isabel herself has been restored despite much devastation by Napoleon’s troops.

The exterior brick and the monastery’s interior demonstrate some of the Mudejar style, where Catholic designers imitated Muslim architecture. Perhaps ironically the array of manacles hanging at the level of the sculptures celebrated the release of Christians from Muslim captors centuries before.

The interior is a bit barren, but includes a charming Gothic cloister.

Also located within the former Jewish Quarter, this pleasant hotel in a stylish, late 19th century building appealed to us when we looked for a place to stay. We slept under the eaves, popping open a window in the roof to look about.

And its history was interesting. It began as a foundry for cold steel of the highest quality and soon ended up as a pastry maker – marzipan, chocolates, etc. – of the highest quality. Both are archetypal Toledo. Hundreds of years before the Romans, and into the 20th century, Toledo made weaponry out of steel. Every other shop in town sells the medieval halberds and such. The other ones sell all kinds of marzipan.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Spain, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)