In brief: The southern route from Batumi to Tbilisi unexpectedly was one our most thrilling – and challenging – drives ever, with highlights like Vardzia along the way.

The southern route back to Tbilisi from Batumi on the Black Sea unexpectedly turned out to be one of the most thrilling drives we’ve done – and one of the most challenging. For hours, we picked our way by mudholes, bulldozer-deep ruts, rockslides, and the construction vehicles trying to create a better road.

But the pleasure surpassed the trouble. It began in winding canyons leading to high mountain vistas. It led past medieval survivors – arching stone bridges, painted cathedrals, and stunning castles. It delivered us to the honeycomb caves of Vardzia. It passed sparkling waterfalls and the vast high plains of the Javakheti Plateau with huge volcanic lakes, edged by towns looking like sets for Game of Thrones. And, for a big finish after two days, it followed the rims of surprisingly deep canyons dropping into Tbilisi. An epic journey.

(Note: The route we drove takes Highway 1 from Batumi to Akhaltsikhe, then heads south to Vardzia and Ninotsminda on the S11, and ends by turning onto the road toward Paravani Lake and Tbilisi.)

We were trying to find that Mirveti waterfall on the other side of the river. The only way to cross to it looked to be a vintage iron bridge of dubious strength and width. Near the bridge, a local man was having coffee and, with some signing and a couple of Georgian words from us, he understood that we weren’t sure about that bridge crossing. “Come with me,” he motioned back. So we followed his old Toyota to the paved drop at the edge of the bridge and – fortunately – did not plunge in the water while carefully crossing after him. It felt much narrower than it looked, especially on the return trip.

Here we are after admiring the charming waterfall near a confluence of two rivers at Mirveti, fascinated by the dropping of the water in delicate tiers along its craggy face, within a kind of mini rain forest. Nearby we discovered an old ivied stone bridge arching over the stream flowing from the waterfall. Sharing the sight and the quietude with just one other daring couple, we almost didn’t want to leave…partly because of the dubious bridge we needed to cross.

Oh, sure, it’s been repaired a few times (haven’t we all??) and we had already found our own much smaller backwoods stone bridge near Mirveti waterfall. But we couldn’t help but be impressed by this 12th century one, nearly 30m (100 feet) across and about 6 meters (20 feet) above the water. Kudos to Nancy for testing the strength of stone arches despite the slenderness of that central part! The larger waterfall near this bridge proved a challenge to reach or enjoy because it was overrun by visitors and vendors of all sorts.

A gorgeous cultivated valley along the road within the mountains.

There were crazier parts of this difficult road, as we wound for hours along the muddy ledges of the mountains, sometimes trailing massive trucks and sometimes narrowly passing by them. But we don’t tend to stop in mid-stream for a photo. Here the construction itself stopped us for about 20 minutes, but it gives you an idea of what else we needed to put up with. We pitied the residents of that little shack to the left, assuming they could even get here.

The medieval Sapara monastery at Akhaltsikhe, nestled in the mountains atop a half-hour long winding road into the backcountry, was surprisingly busy when we visited it late on Saturday afternoon.

A host of cars filled with very well dressed Georgians dropped people in the parking area below so they could walk up and offer individual prayers with lit candles inside. A few vans came too, dispatching more elderly visitors off on the same mission. On the way back down, the twists of the road were slowed by all the returning traffic. We thought perhaps that locals felt a special holiness about this place so they took the time to come here before, perhaps, a wedding feast or other celebration in town.

As we entered the main church at Sapara, the 14th century frescoes of the monastery startled us with a glowing intensity that contrasted dramatically with the muted hues of its stone construction and the quiet natural setting of the green hills.

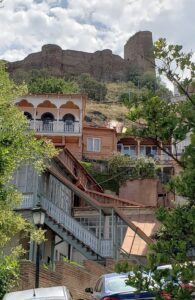

One of several remarkably preserved medieval fortresses along our route, this one at Khervisi near Vardzia. There should be dragons to match!

A typical mountain vista on our route.

We didn’t get as good a photo of the lakes we passed, but this is Madatapa Lake, one of the lakes of the high Javakheti plateau between Batumi and Tbilisi. (Source: Paata vardanashvili – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 at Wikimedia)

Vardzia

In the end our legs felt a bit rubbery. We spent several hours scampering along a cliff face, hunching down to follow narrow passageways, and climbing uneven stone steps. But it was all worth it to marvel at the extraordinary cave city of Vardzia in southern Georgia.

Dating mainly from the 12th and 13th century, this natural rock-cut fortress once housed 50,000 people. Multi-room apartments, dining halls, bakeries, apothecaries, wine cellars, aqueduct and water storage, even a stable for horses – all made for a fully functioning – and hidden – troglodytic city. An earthquake sheared off the façade revealing the caves and by the 16th century the Ottomans finished the job.

Vardzia today on its cliff face. Nearly all the cave openings were hidden before the 13th century earthquake exposed and damaged the city.

But there remains a warren of perhaps 500 caves, linked by tunnels and staircases deep inside – spanning half a kilometer and 19 levels. The pivot point is a beautifully frescoed church, once a significant medieval monastery. What remains of Vardzia left us with awe, as well as aching legs.

The many levels of Vardzia some 100 meters (over 300 feet) above the valley floor, with its intricate linkages of caves via old stairs and new. At times we felt we were walking through an MC Escher print, with confusing stairways linking the many caves we visited. Looking back at this, we couldn’t figure out how we reached this viewpoint.

This is a one of the tunnels deep within the mountain through which we needed to crouch and skitter up and down. This one led us to some hidden caverns, including a kind of rock-hewn castle keep where residents could hide if the city was attacked.

Frescoes inside the 12th century cavern of the Church of the Dormition, which was carved into the mountain in the form of a typical Georgian church. We could only locate it at the end of a difficult passageway, barely detectable except for the bells hanging there. Various tunnels led from the church to a spring that still flows within and to chambers once used by monks. On the left is a vision of the heavenly host, to the right Mary is honored on her deathbed, and in the middle a very non-DaVinci Last Supper.

Some rare and important paintings from the Church of the Dormition celebrating patronage as well as holiness. These frescoes honor the rulers Queen Tamar and King Georgi for their gift of the church (to the right), and various other saints and heroes on the left.

Another look at the caves accessible today from along the cliff face. What you can’t see are the still hidden passageways hacked from the rock within. But most of the cavern openings were once dwellings.

All the comforts of home…an example of a cavern apartment at Vardzia. Through the portals in this family room you could reach several other rooms for sleeping and other domestic uses. Other holes let light through. The carved niches were used for seating or storage. Residents used the tear-drop hole on the floor at the left for cooking/baking with firewood placed into the narrow extension. The wide channel curving around it was for feet: people sat on the raised part to eat – or perhaps to cozy up to the fire on a cold night.

The fertile valley beneath Vardzia caves. That square structure on the cavern cliff to the right is a 14th century bell tower built after the destructive earthquake.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Georgia, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)