In brief: São Roque was a shrine honoring a protector, then a heavenly 16th century church. Grand chapels enhanced it over time, but little of its rich history was lost.

A pandemic threatens Portugal. People are dying across the country. What’s the government to do? In 1505, the king sought divine assistance through the mediation of a man considered a savior from the plague 150 years before, Saint Roch (São Roque). In response, a sympathetic Venice sends a remnant of the saint to Lisbon. This is eventually placed in a shrine in the midst of a graveyard for the victims of the plague near Chiado, Lisbon, and tended by a dedicated brotherhood.

Here is some of the great beauty and fascinating history we found when we revisited the church and museum of São Roque.

Shrine

The 1505 relic of the 14th century man, Saint Roch, now sits in the museum next door to the church, displayed in the glass window at the top of the mini-obelisk. The museum also features a wonderful collection of art and adornments from the church, and illustrates the story of shrine and church.

These vivid 1520 paintings from the original shrine’s altarpiece show highlights of the life of São Roque, including the bottom right panel where he cures a bishop, presumably of the plague. These are now featured at the museum.

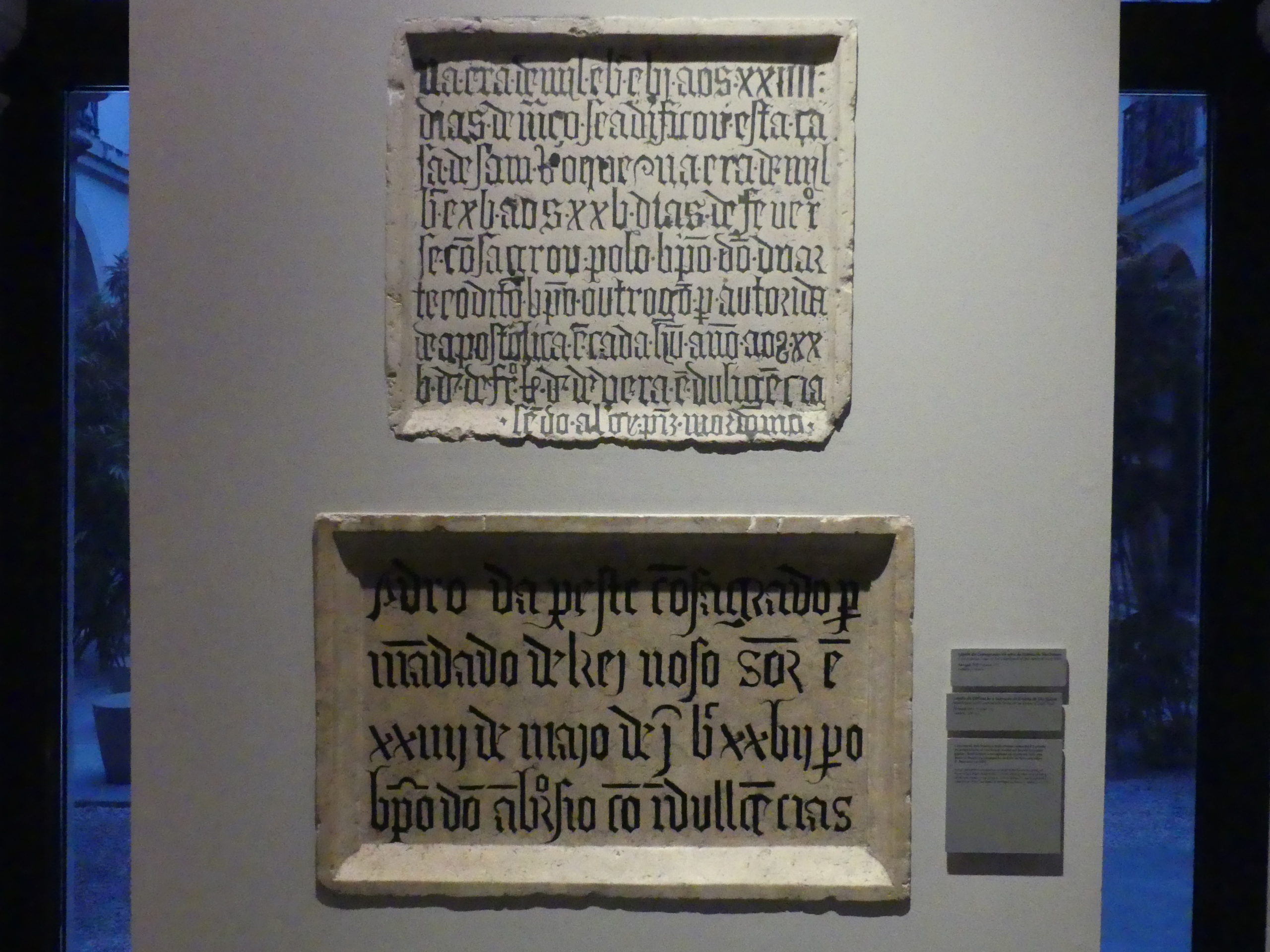

Two more original pieces in the museum from the early 16th century shrine are these stones, commemorating the shrine’s consecration (top) and its graveyard’s consecration (below).

The Church

A few decades after the building of the shrine to São Roque, the Jesuit order here incorporated it into a grand new church of São Roque.

The aim of the Jesuits was a harmonious and inviting hall for worship. That same hall greets the visitor along with the two centuries of resplendent chapels they also created and that still grace the church

The elegant 16th century interior of the Church of São Roque, nicely accented by the glow of its side chapels and still sheltered by the intricately painted, trompe l’oeil wood ceiling from that time. The flat surface seems to be a barrel vault and the elliptical sections appear to be galleries open to the skies.

Though the altar and chapels reflect various styles from the next few centuries, the interior remains a harmonious blend. The open auditorium space satisfied the Jesuits’ aim to preach lessons to the churchgoers.

The most expensive chapel at the church, festooned with precious stones and elaborate workmanship, ironically honors the austere, anti-materialistic John the Baptist. This was a project of King Joao V, wealthy from the gold and diamonds of Brazil in the mid-18th century.

The Baptist chapel was built in Rome, placed in the Saint Anthony church there for a papal mass, then disassembled, shipped on three boats to Lisbon, and reconstructed at São Roque.

And an elaborate 18th century chapel on the other side of the hall, Our Lady of Mercy or the Calvary, named for the dual figures of the crucifixion and the pieta.

The polychromatic wood carvings, including a bounty of cherubic figures, are elaborate Baroque fancies.

Museum

In addition to featuring the art and artifacts of the original shrine, the museum presents other admirable works.

An elegant display hall in the museum reminds us that the building was once the residence for the Jesuit leaders.

Some of the riches of Joao V were used to create gold church implements and other glittering objects on display within the museum. This assemblage of canopy, tapestry rug, elaborate man-sized candlesticks and altar with a silvery Last Judgment were among his gifts when he created the chapel honoring John the Baptist at the church, perhaps the costliest of its time.

The powerful agony of this depiction of Jesus on the cross disrupts the calm of the museum.

Made of ivory in India, it is part of a featured collection of church items demonstrating trade – and religious interaction – with Portugal’s colonies, sources of the country’s riches.

A colorful early 16th century limestone image of São Roque bids adieu. His beneficent presence presumably warded off plague at the eponymous portal of Lisbon’s old city walls until 1835, after miraculously surviving the famous, massive 1755 earthquake intact.

He still salutes visitors as they arrive and depart – and wards off disease – but now in the entrance hall of the museum.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Portugal, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)