Canyons and sand, water and greenery, oases and beaches, flatland and mountain – this is the delectable diversity of southern Jordan’s desert, as we experienced it in three locations.

Wadi Rum – the high desert

Petra is in the middle of the desert in southern Jordan (see our post about Petra), but there is much more desert to explore around here. Less than two hours drive away from Petra is Wadi Rum (Rum Canyon).

At over a mile in altitude (1,750 m), it’s an extraordinary landscape of red sand, echoing canyons, hidden springs, imposing mountains, and weird sandstone formations.

Its out-of-this-world appearance has given it a starring role in movies such as The Martian, Rogue One, Aladdin, The Rise of Skywalker and Dune – as well as Lawrence of Arabia, where much of the movie was filmed, partly because he stayed here for a while during the Arab Revolt.

Reportedly the stone wall in this photo marks the house where TE Lawrence lived in Wadi Rum while he prepared for the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman rule in 1917-18. Most visitors climb up to the plateau above it for a fine view of the area. Elsewhere at a natural spring someone carved a small portrait of him into a prominent rock, as well as another one of the Arab leader Emir Faisal.

On camelback, Bedouins have traversed the subtle trails here for millennia, camping on the sands and tending their sheep.

By camel, the Bedouins still move some goods from place to place. And, for the tourists, Bedouins operate ambling camel excursions through the Wadi.

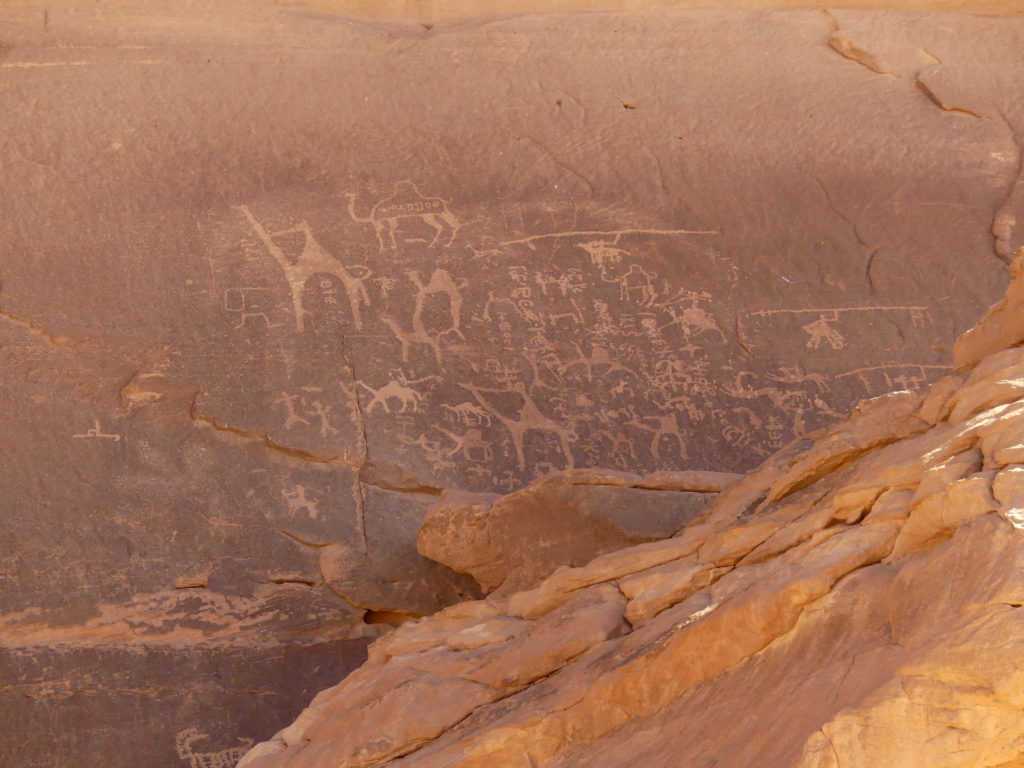

Over the years, the nomadic Bedouins adorned their routes with such figures as these, etched into the sandstone surfaces.

This group includes a lot of camels, but its most interesting part to us were the human figures on foot to the left and at the right on camelback with long poles, perhaps hunting. In other spots, merchants crossing the desert left old Nabataean (the Petra guys) and Arabic inscriptions with advice. One began with a prayer to Allah in thanks for help, then directed passers-by to a source of water in the adjacent canyon.

Much of the desert lodging here consists of touristy versions of Bedouin camps with fancier goat-hair tents or hotel rooms in brick huts. Other lodging includes glamping bubbles like these with lots of amenities. Ours were nestled at the base of a stunning mountain, with a vista over the desert. By the time we reached Wadi Rum, with the drop-off in tourism due to the covid-19 pandemic, we only saw three other couples here during our three day stay.

But we did see lots of others as we crossed much of this extraordinary 720 sq. km (280 sq mi) terrain by 4×4 and foot.

Here are some highlights.

There are several natural arches in Wadi Rum.

This is one accessible enough and strong enough for the courageous to cross it.

Perhaps the most unusual and evocative of the mountains we saw.

Another tall mountain seems to consist of seven interlocked pillars, so it has been renamed in honor of TE Lawrence’s autobiographical book about his Middle East experience, The Seven Pillars of Wisdom. We found this one much more visually interesting.

This smooth face, the result of a collapse of its rock wall, fascinated us for two reasons.

First, the beauty of the surface exposed along with the force implicit in the collapse. Second, how the Nabataeans of Petra must have learned from this natural phenomenon about using such a surface to sculpt elaborate facades on it. (see Petra)

A beautiful narrow canyon, or Siq, at Wadi Rum lights up the scene below. This led to a spring that filled up a natural basin downstream during rainy times.

A typical broad canyon where the red sands flow between sandstone mountains. This looks easy to find, but we discovered that ease is an illusion. Once you pass through the narrow end of the canyon far to the rear and look back, you cannot readily tell where the passageway lies amid all the rocky outcroppings. The desert can be disorienting in many ways.

Splendid erosion along the sides of another canyon where we stopped for our own Bedouin tea, made with cardamom.

Shape and color in endless variety continually attract your attention in Wadi Rum.

Dana Biosphere Reserve – four ecologies crowding the canyons

When people think of desert, they often think of red sands drifting out to the horizon or scraggly rock-strewn hills or a kind of wasteland of dry terrain with little vegetation. In the deserts of the Middle East, as at Wadi Rum, you see all of these things, but you also find ancient canyons, or wadis, around which life teems – including the shepherd life of the nomadic Bedouins.

For, as it has for eons, nurturing water flows during the rains; underground springs support greenery and wildlife.

At Dana in southern Jordan, we walked through one sinuous wadi which was damp at times, with a soft muddy sand, but serenely free of flowing water. Another was unwalkable due to flood waters coursing through it.

The wadi we walked was replete with free range goats and typical Bedouin tents.

We were told that the goats – who are amazingly surefooted on the sides of these rocky hills – always return to their correct owners. There they can rely on sustenance other than the plants, and feel at home, one presumes.

Bedouin life is often romanticized, and imitated in a glampy way for tourists who love settling into goat-hair tents outfitted with conveniences. This is a more typical Bedouin residence, easily packed up and moved to pursue the best places for their livestock to feed. They are often huge to accommodate a social area, sleeping area for an extended family, plus maintain separation of men and women. But, like these, most are formed from commercial sacks, adverts and other found materials.

Wherever they find themselves, the nomads maintain a strong culture of gentility and hosting of strangers. Here our host demonstrates how to make and serve Bedouin coffee. He grinds the coffee beans he has just pan-roasted, before boiling them in a traditional pot, whose sinuous look is almost a symbol of the country. The secret ingredient, ground with the coffee beans, is cardamom seed.

Throughout this desert, the wadi and the Dana preserve, the beauty was evident.

In a striking tuxedo against the brown tones of the desert: a white crowned wheatear.

At times, flowers appeared in the most surprising places, like these daintily popping out from the rods of a paloverde-looking plant.

And one other of the many birds who love this terrain: a Palestine sunbird, here dining within a flower’s cup.

Our ecolodge nestled into the broadening lower end of the wadi’s hills – made of natural materials and powered mostly by solar.

At night in the lodge, candles and lanterns were the main source of illumination, providing an appealing glow throughout.

Aqaba – a Red Sea oasis complete with beaches and trade

At the top of the Red Sea lies Aqaba, Jordan’s southernmost city. Driving along its palm-lined boulevards and past some ostentatious wealth unusual in Jordan, Aqaba feels like an oasis rimmed by the sere mountains at the edge of the desert – and the crystalline sea. The terrain is especially charming in the late afternoon light.

The Red Sea attracts tourists who prefer beaches, diving and snorkeling. Nancy’s broken arm from a few weeks earlier still had limited motion and water sports were unappealing due to the cold and often choppy waters during our stay. So instead we walked the main beach, enjoying Aqaba’s array of upscale food options, sights and sounds.

Sunset on the long city beachfront in Aqaba, where people gather all day. Local women do not remove their cover-all clothing, so westerners are encouraged to follow custom and reveal little skin. Most did not seem to comply.

Along the main public beach, operators and shills for glass bottom boats trawled for Jordanian and foreign tourists who wished to see underwater but not get wet. Toward evening, they become an option for sunset cruising as well.

One unusual feature of the long Aqaba beach in town are the plots of spinach and radish plants, among other things, that fill in the space between the corniche road and the sandy shore. And, yes, vendors sell the produce on the walkway.

With close land access to Eilat on the southern tip of Israel and sea routes to nearby Egypt, Saudi Arabia and beyond, Aqaba is also a thriving commercial center, as well as a crossing point for foreign visitors to Petra, Wadi Rum and other nearby sites.

At some vantage points, you have four countries in your grasp. This is a rooftop view over the Red Sea, with Eqypt’s Sinai Peninsula and Israel to the right and, to the left, Saudi Arabia just past Aqaba’s port operations and the Jordanian hills. In 1965, Jordan enabled more commercial activity here, when it acquired from Saudi Arabia some of the coastline south of Aqaba in exchange for a chunk of its desert land.

There is a bit of older history here too. In the first millennium AD before a destructive earthquake hit, Aqaba, or “Ayla” then, thrived as a crossroads for pilgrimages to Mecca and trade across the world. Some interesting ruins of Ayla date from the second half of the millennium, when Islamic Ayla traded with Asia, Africa and the Middle East. These arches formed one of the gateways into the city.

This gateway contains three layers of later history. Built in the 16th century, the structure beyond it served as an inn (khan) for pilgrims on the way to Mecca, to the south in Saudi Arabia.

These lovely inscriptions from the early 16th century, in what became the Aqaba Fort, attest to its usage as an inn.

The Ottomans fortified it later but lost it when the Arab Revolt triumphed here in 1917 under Emir Faisal (and TE Lawrence). The crest above the entry to what is now known as the Aqaba Fort commemorates the ascendance of the Arabs at that time. And then the British took charge instead.

Politics continue to preoccupy the region alongside the natural delights. This panorama comes from a relatively new bird sanctuary 5 kilometers north of Aqaba, now a lovely place to wander and a refuge for migrating birds.

The tricky part is reaching it, as we had to meander along poorly signed asphalt roads near Aqaba’s airport, then pass a Jordanian checkpoint. There they took our passports because reaching the wetlands entrance required that we drive to within a few hundred meters of the Israeli border checkpoint.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Jordan, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)