In brief: “Vast dry plain” – what Namibia means – describes most of its landscape. But we found such beautiful variations of hills, desert plains, sand, water and rock.

Namibia means “vast dry plain,” and that sums up most of the landscape except for the fertile north described in our last post. But those words don’t do justice to Namibia’s endlessly beautiful variations on hills, desert plains, sand, water and rock.

We spent a bit more time in some areas of the country, as highlighted below in this post. These include Etosha and Caprivi Strip in the north as well as Fish River Canyon in the south. In a separate post, we talked about the extensive sand dunes for which Namibia is especially known (click to see that post).

Here are views of some of the most appealing terrain, as we looked back on our trip through the country.

Etosha

At the top end of Namibia sprawl the Etosha pans, a national park and wildlife preserve since 1907 set around a seemingly hostile environment of salt flats, roughly 130 km (80 mi) long and 50 km (30 mi) wide. With little rain that briefly fills the pans, only the heartiest of animals and plants can survive, mostly at the fringes where underground water still nourishes vegetation.

So it’s astonishing to see how many species do well here. Such conditions make it easy to find them too, as most of the activity centers around the waterholes, natural or now man-made from boreholes.

A waterhole at Etosha hosts many springbok and, in the background, oryx and kudu antelopes.

Red hartebeest, with beautiful coat and coloration, approach a waterhole over a rocky, salt terrain. They are among the sleekest of antelopes, and look oddly stretched thin in photos.

Black rhinos are not black, but their counterpart species ‘white,’ a mistaken translation for the word ‘wide.’ The black rhinos have a narrow, triangular mouth; the white rhinos have a wide mouth.

Visitors gather at the waterholes to watch animals, like these two, gather at the waterholes. If you stay in the park, you can sit along an esplanade facing this waterhole, especially during the cool of the night when driving through the park is finished.

In the course of one day – and night – we saw rhino, hyena, giraffe, herons, lions, and various antelope here. The odd lighting humans need at night to see them is supposedly animal-friendly.

A small antelope endemic to this area, the Damara dik-dik, has the cutest ears.

We have seen that antelopes and other animals usually keep away when lions are at a waterhole, however thirsty they are.

Here other animals still drank at the waterhole, because of the very full stomachs of this male lion and a few females, who were sprawled out like this at the water’s edge. The lions had recently eaten their fill and were not a threat.

A herd of zebra crossed the pan road in front of us, but this one seemed to strut and preen for us.

This older elephant, it’s tusks broken from past tussles, was one of many we saw – along with, surprisingly, many giraffes. He was headed our way as if to cross the road we were on. But he ambled so slowly that we moved on long before he arrived.

The double banded sandgrouse, so-called because of the racing stripes on its bill, is one of hundreds of bird species at Etosha.

When wet, the pans host pelicans and flamingoes also.

Black rhinos spotted during the day’s drive along the fringe of the pans.

And something completely different – at Namutoni, where the dry pans yield to the riverine lands of the northeast.

Here, while colonizing Namibia, German troops built a fort in 1889 to confront the local tribes, who destroyed the first one. Rebuilt, it became a facility within the wildlife reserve.

Caprivi Strip

The northern area of Namibia is far different from the bulk of the country, because it is made fertile by several rivers like the Okavango and the Zambezi.

When the country became independent from South Africa in 1990, it still suffered from apartheid.

The dry ranching lands to the south were allocated to whites out of South Africa, while the Ovambo tribespeople were hemmed into the poorer north.

Now this section is quite productive as well as a traveler’s delight due to the wildlife attracted to those rivers. Namibia even extends 450 kilometers (280 miles)to the east along the Zambezi River with a strip of land just 30 or so kilometers (20 miles) wide.

A bit east of here, at the end of the Caprivi Strip, you can – in theory – stand on a spot where four nations meet, which would be the only multinational quadripoint in the world. The juncture was even fought over as late as 1970. However, several agreements to create a ferry service across the Zambezi have blurred the borderlines so that this might really be two tri-points…and inaccessible to us anyway due to ongoing construction.

This Caprivi Strip derives from a mistake by late 19th century European powers, granting the river corridor to Germany (under Leo von Caprivi) so it could access the east coast of Africa. The Germans didn’t account for a major obstacle, however, the river’s unnavigable 100 meter (300 foot drop) at Victoria Falls.

We saw mostly well-kept villages along the Caprivi. Here are two, one mostly brick and one mostly wood, but both demonstrating a higher level of prosperity than in the apartheid past.

Shebeens arose from restrictions on bars and alcohol consumption by the governing South Africa leadership.

In the past, the shebeens were generally family homes that operated as unsanctioned, informal bars – a means of protesting and resisting those apartheid laws. Now they are licensed drinking places where people can still argue politics and socialize. The names evoke religion, like Top Life pictured here, or good times (The Jive Shebeen).

A rocky section of the Okavango River

Oddities in the Desert

Welwitschia mirabilis. A plant endemic to rocky Namibian deserts, the Welwitschia grows only two leaves, which channel the minimal desert moisture down to its base.

Over time, wind shreds the two leaves into many parts, but they remain unpalatable to all animals. The Welwitschia don’t flower at all until they are 20 years old and can live for 2000 years in these harsh places.

Fish River Canyon

To reach Fish River Canyon, we needed to pass through Namibia’s austere southern landscape of scrubby desert, sandy kopjes (small hills) with volcanic rock strewn all over them. On many of them, as if emerging from rock itself, stand the umbrella-struts of quiver trees, the source for arrow-making for the indigenous San people.

And the landscape was also adorned with heaped boulders, “Garden of the Gods” mountains, whose large rocks, left from eons of erosion, seem tossed by Titans.

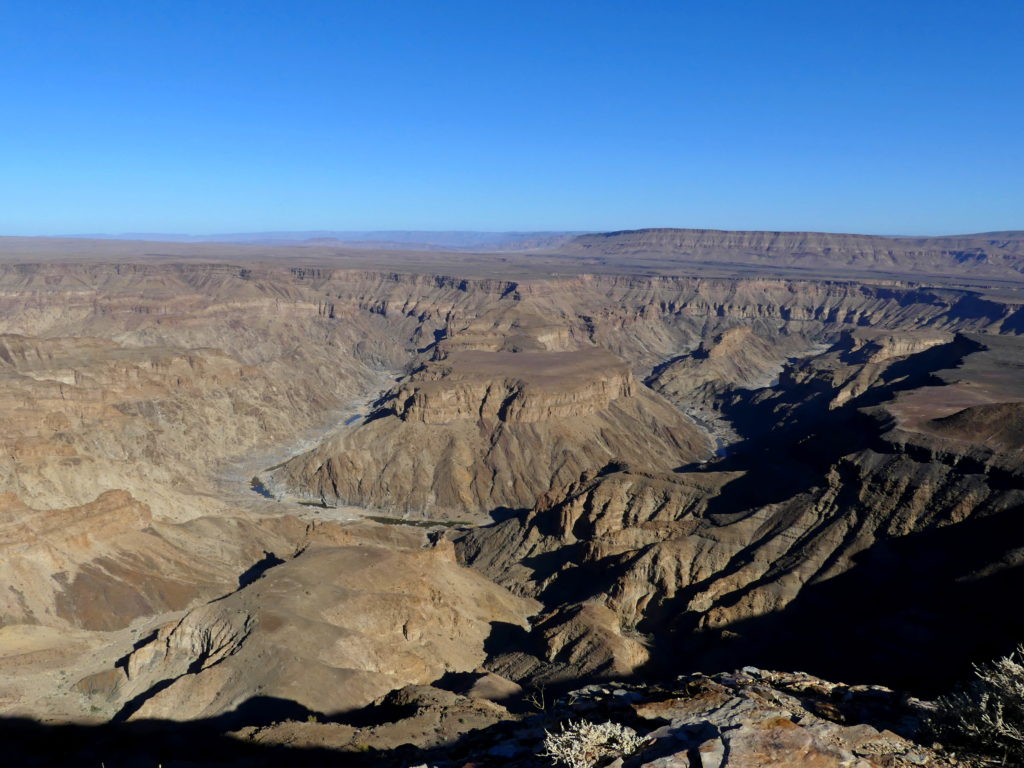

The canyon is considered, depending on the source and the means of measurement, second only to the USA’s Grand Canyon in size.

Through a final desert pass, we reached two oases of a sort. The first was Ai-Ais, a natural hot springs at the lower end of Fish River Canyon. The second was the canyon itself, a colorful melange of sandstone rock and minerals, with a mostly dry bed at this time of year. From our viewpoint at the halfway point of the canyon, we could have trekked four to five days along the bottom, some 80 kilometers, back to Ai-Ais hot springs.

The suffocating afternoon heat along the riverbed and the chilling cold nights did not inspire us, though surprisingly many people did the hike. We spent a few hours walking along the rim in the cool of the morning instead, quite pleased with the view of the canyon unfolded before us.

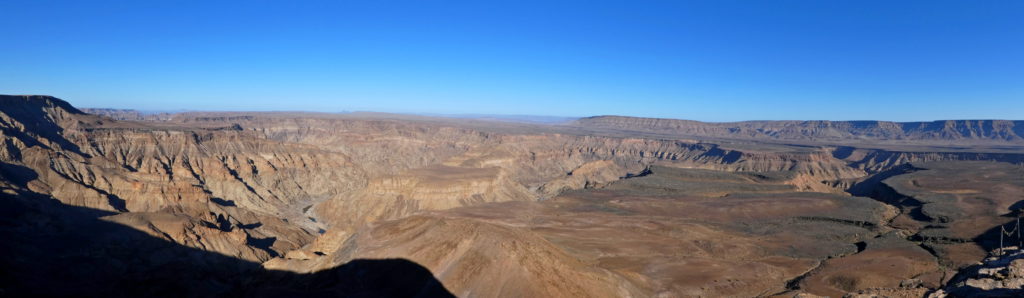

The canyon is especially interesting at times because it features two levels: the cliff top is about 550 meters (1750 feet) from the river bed, while a terrace-like level is several hundred meters below that.

The most picturesque section of the canyon, where the river made an arc-like bend long ago. As with most desert rivers, when it rains upstream, the water fills and flows quite rapidly. We could see a bit of water pooled in spots at the bottom, but there was no true river at this dry time.

You don’t spot many animals here, but some thrive on the austere conditions. The Klipspringer is a natural rock-hopping antelope, with strong back legs and the most interesting ears. We saw three of them powering up a steep hill, pausing only to watch us alertly.

Fish River Canyon panorama, with the u-shaped bend of the river to the right. The intermediate terrace level of the canyon is also evident to the right.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Namibia, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)