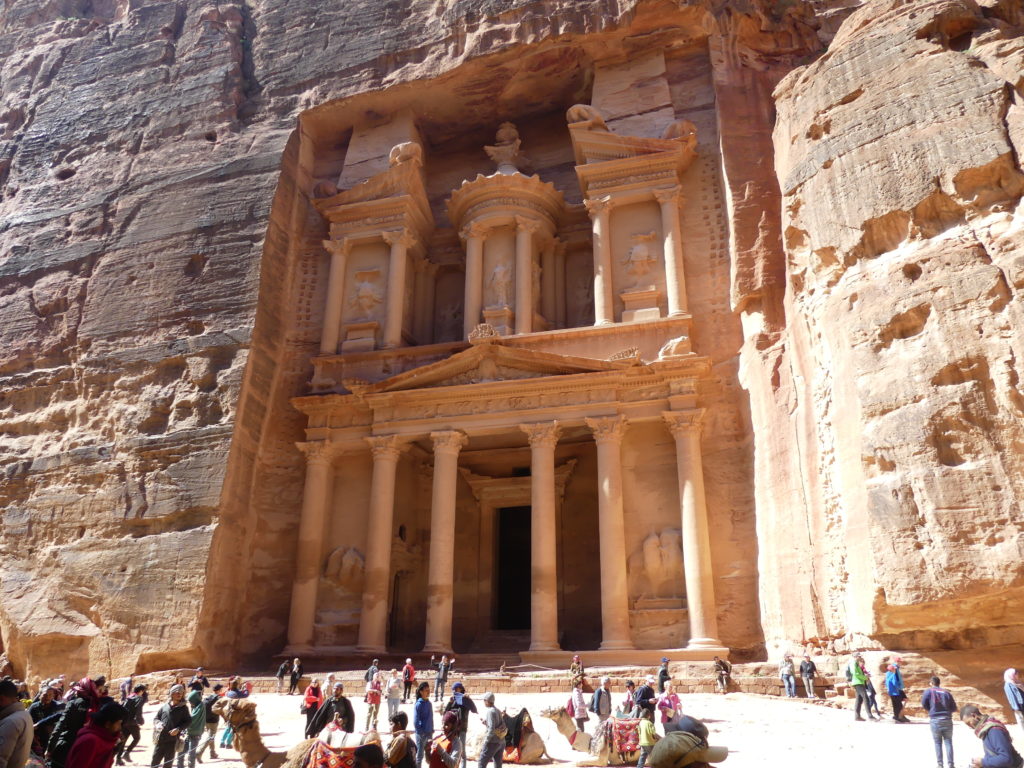

One of the new Seven Wonders of the World, Petra truly deserves that designation, but not because of its signature sight, the carved façade known as the Treasury. Tour groups come in hordes to make the obligatory half-hour pilgrimage to it through the colorful narrow canyon of the Siq – or opt for a quicker horseback or horse cart ride.

Some take the better part of a day to continue past the Treasury toward the two-millenium old Nabataean city of Raqmu (Roman Petra) and then back out again, inevitably dazed by the innumerable delights of the journey.

But even such a long day skims past a vast landscape of stunningly carved tombs, sandstone cliffs, winding canyons. And cultural history: the empire of the Nabateans controlled the region for about 500 years, thriving on regional trade that included the sale of frankincense, myrrh and other spices. The 800 different wonders (including 500 tombs) at Petra plead for at least a three day commitment, and reward those visitors who stay to savor them.

To show just some of its wonders, we take you along the main trail to the city of Petra. And then hiking on two of the most spectacular climbs off the trail.

We also took the time to visit Little Petra, a much quieter place of interest in the vicinity.

Little Petra features a small Siq canyon, a few fine tomb facades, a narrow climb to another canyon, as well as a wonderful landscape to explore in the area. Worth a day in itself. This tomb with another classical facade is the most attractive carving at Little Petra. Its small interior features quite lovely streaks of color and, unusually, a formal interior decorated with leafy frescoes and a naked flutist.

Along Petra’s Main Trail

The colorful approach to the Treasury and the rest of the city of Petra winds through a narrow passageway called the Siq.

Along the sides of the canyon, we could trace channels that had brought water from the springs and rains of the upstream canyons of Wadi Musa to the ancient city within. You could enjoy many hours here just watching the shifting sunlight dance along the rocks.

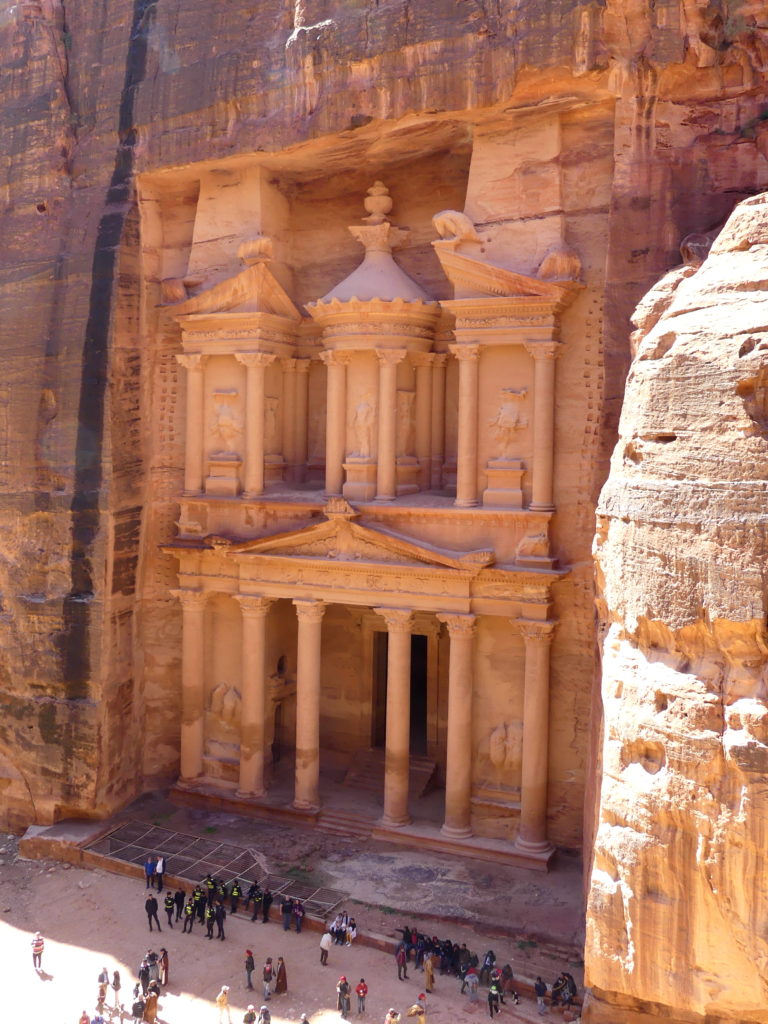

The so-called Treasury, al-Khazneh, as viewed from a broad eyrie atop a short, but challenging climb. The name is just one of the misconceptions about this carved masterpiece.

Long-time legend said that it housed a fortune, and so a Treasury (the solid rock of the urn on top became a target of bullets). But it’s really a tomb for one of the kings of two thousand years ago, carved with great precision from the top down above an older set of tombs. Though a sizable space has also been hacked from the rock past the main door, it’s not the elaborate cave that Indiana Jones must master to save his father. It’s also not the largest or, to us, the most magnificent of the tombs.

The guidebooks talk about its blend of Hellenistic classical style (the strikingly broken pediment on top, the columns and friezes, the eroded statuary in the circular part, etc.) plus the Nabataean decoration.

Yet we were struck by how this and the other tomb facades were inspired by nature. Throughout southern Jordan, we saw huge sandstone surfaces smoothed off after hunks of a mountain sheared away. Natural bulges in those surfaces looked like columns and statuary. The Nabataeans learned how they could take nature one better, we thought, and carve much more elaborate designs into these rocky canvasses.

A side trail off the main one heads past a group of Royal Tombs, some of which rival the Treasury in splendor.

This is the multi-level façade of the Urn Tomb. Each opening leads to a chamber carved out from the rock, but the rock face creation is the attraction.

The interior of the Urn Tomb with niches to honor the dead. In many tombs like this, the space carved out reveals swirls of color created by veins of mineral deposits.

Going further along the side trail with the Royal Tombs leads to the two more elaborately carved facades: the complex five-story façade of the Palace tomb (which might have been a triclinium, or meeting hall) and the Corinthian tomb on its right, whose eroded top part mimics the Treasury.

One of the pleasures of staying late into the afternoon at Petra is watching how sunlight tints the sandstone surfaces. This is the afternoon view of the Royal Tombs from a hill above the central city of Raqmu (or Petra).

Past the Treasury and about half way to Raqmu, or Petra City, is this striking array of small tombs that look like a modern set of condominiums, somewhat classical in style. Some are now occupied at times by the resident Bedouins who offer the horse or camel rides, sell handicrafts and souvenirs or operate the cafes.

Other niches offer a place for camels or donkeys to hide out.

The Great Temple is the largest and the most noteworthy of the buildings within old Petra city, 7000 square meters (about 80,000 square feet) and close to the end of the main trail.

Below the temple, along its base, run a colonnaded street and the remains of an elaborate gate which once was adorned by sculptures of mythical creatures and gods.

Some of these decorative figures, like this striking Sphinx, still gleam at the Petra Museum near the visitor entrance to the main trail – a collection worth another few hours here.

A large ruined blockhouse of a building and other small structures sit to the right of the Great Temple, as does the busy Petra restaurant. This view is from atop a low hill across the street, where you can visit several old temples from 2000 years ago and 6th century Byzantine churches with fine mosaic floors.

High climbs of Petra

There are quite a number of hikes and climbs away from Petra’s main trail, well worth staying and paying for extra days at this site. We did two of its best ones: the Monastery hike and the trail to the High Place of Sacrifice.

A panoramic perspective…At the lip of the plateau with the sacrificial altars, we savored this panorama of nearly all of Petra, backed by its bulbous mountains.

The ancient city lies to the left of the valley 200 meters below, from the base of the mountains to the Great Temple at its right, with the remains of Byzantine churches up on the low hillside nearby. To their upper left, at the top of the mountain range, is the location of the glorious Monastery tomb. In the lower right corner stand the wondrous series of Royal Tombs shown earlier. And the Jordanian flag states its claim over all.

Monastery trail

The trail to the Monastery tomb starts at the old city, about an hour’s walk from the visitor entrance.

It then winds through a narrow canyon up 200 meters in altitude (700 feet) on roughly 800 steps, past numerous trinket stalls.

An extra treat during the climb to the Monastery is a short, but tricky, side trail to the Lion Triclinium.

It’s a lovely little façade, past whose keyhole entrance lies a carved interior where people gathered for ceremonies. The name comes from the two alert lions flanking the portal. We were more intrigued by the little faces with knotty hair at the edges of the narrow frieze.

The 800-steps cut through lovely sandstone canyons, a spectacle in itself, with frequent views back to the other mountain ranges and valley.

The trail ends just to the right of the façade in the photo below. In the vast open space lies a low-walled, circular forum of white stone whose purpose wasn’t exactly clear to us.

This magnificent view of the tomb is from the upper ridge line of the mountains behind Petra city. Even its setting is impressive. The entire square plaza at the tomb’s base is cut deep into the pyramidal mountain, not just the façade.

The Monastery (ad-Deir in Arabic) in a full frontal pose, inset within its original sandstone mountain. Its 45 x 50 meter surface is much greater in size than the Treasury.

As with all the tombs, this was carved from the stone by Nabataean artisans from the top down – directly out of the rocky mountain, with no do-overs. In its design, the Nabataeans mixed Mesopotamian and Greek classical styles. The name derives from crosses later cut into the walls during the Byzantine era, not from the Nabataeans who made it hundreds of years earlier.

Our favorite element here – and at the Treasury on which this was modelled – is the triangular pediment designed as broken in two in order to salute the spot of honor in the cylindrical section at the middle. Statues once graced the open niches. At the very top perches an urn, appropriate to a tomb. Eight columns on the top level match eight different ones on the lower level.

Continuing to the ridge beyond it delivers some spectacular landscape views as well.

Even on a hazy, cloudy day, the view from the peaks near the Monastery was invigorating. On clear days, you can see Israel and the Palestinian Territories over the neighboring mountain ranges as well as several wadis (river canyons) in Jordan. In the mountains nearby, it is said, sits the tomb of Aaron – Moses’ brother – a local pilgrimage site.

High Place of Sacrifice trail

The best option for this trail is to make a circuit that includes the long staircase to a sizable plateau where the altar was, an equal height as the Monastery climb, as well as following the sublime Wadi al Farasa canyon around the back that ends at the old city of Raqmu.

We started along the back way from the old city and ended by descending the stairs. For hours along that route we passed sprawling sandstone mountains riddled with tomb niches and many other elaborate entrances to little seen tombs and meeting halls.

The name of this, the Tomb of the Soldier, derives from the three statues in military costume set in the upper niches. It is one of the highlights as the canyon narrow. We thought that the liquidy erosion of the façade itself made it seem carved from wax.

We’re looking at it here from inside the somewhat eroded entrance of a triclinium, or gathering hall, opposite the tomb – unique in itself because, unlike most halls, its interior was decorated with carvings. At the triclinium, people would gather for ceremonies to honor the dead. In between the two structures had been a wide plaza, now broken up and littered with old columns and pieces.

Another charming place along the canyon is the Garden temple, which seemed ready for a party on its deck. To its right in the photo is a well fed by a natural spring, which is dammed by a bricked wall adorned with plant life.

We mounted stairs steeply cut through colorful passageways.

This one was easy compared to the very steep set of stairs cut into a vertical wall at the back of the canyon, ending up just below the Sacrifice altar.

Somewhat below the Sacrifice altar, we came face-to-face with this larger-than-life, five meter long Lion fountain, a gorgeous high-relief sculpted from the rock.

The head is gone, but you can just see a dug-out channel at the lion’s upper right which gushed water through its mouth. You’re often aware at Petra of the vital importance of water in the desert. The mile-long sandstone canyon entrance, or Siq, into Petra includes channels carved by the Nabataeans to bring water to the city. They proved very sophisticated elsewhere at moving the water where it needed to be – and, as here, taking advantage of natural springs in the porous rock.

This is the main section of the High Place of Sacrifice, where Nabataean priests did their rituals. Even after 2000 years, the mechanisms of the site are evident: the altar for the slaughter and channels to stream the blood away – all hewn from the flattened surface of the rock – plus a kind of a sacristy in the carved niche.

Most of the ritual area consisted of a large rectangular space dug out just below this, and which might have accommodated attendees. Some archaeologists think that the Nabataeans sacrificed humans at times, but most evidence is that animals were the victims.

The route down from the altar is the long staircase that winds through a narrow cut in the mountain.

Before descending in the waning light of day, we sat in awed pleasure at sweeping views of Petra’s landscape in the Wadi, full of color and forms, as well as its other features – grandeur that might even have distracted those Nabataean priests.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Jordan, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)