We were thrilled during our long, leisurely visit to “Superstar Pharaohs,” a rewarding exhibition at the Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon. We took our time to peruse 250 pieces that show how the history of the Egyptian kings had been recorded, effaced, and regularly manipulated over time. How did Rameses become so infamous? Or Cleopatra? Who the heck was the mythic King Sesostris? And how were Akhnaten, Nefertiti, and King Tut all but forgotten, but then miraculously rediscovered as pop superstars? And what was Gulbenkian’s connection to all this?

The exhibit featured striking Egyptian artifacts from up to 5000 years ago. Other displays illustrated what the ancient and modern world understood about Egypt’s kings, and why anyone cared. These showed vividly how history is often transformed to support the interests of those who retell it.

And the cost was just $5, with half-price for seniors. Free on Sundays after 14:00. Our visit was greatly enhanced by accessing the excellent exhibit explanations on our phones using a single QR code or this link:

gulbenkian.pt/museu/en/chronologies/object-labels-superstar-pharaohs-exhibition/

(13th century BC) For the Egyptians, remembering and ritually celebrating a dead person ensured their eternal life. The show starts with this idea in stone. This offering table records the emblematic cartouches of recent kingdoms up to Rameses II. But it excludes the heretical Akhnaten, who worshipped a single god, thereby writing him out of history.

(As early as 18th century BC) This graceful and intense portrait depicts Senwosret I as he familiarly embraces the god Horus, who is depicted with his falcon head at the bottom right, as well as by the resplendent winged sun overhead. But the stele was fashioned more than a century after Senwosret ruled to keep him in memory and share a bit of his glory.

(4th century BC) This mini-Sphinx from the reign of the later Pharaoh Nectanebo I is as serene and beneficent looking as a Buddha. That king aimed to align himself with the virtues of the renowned Senwosret, 1500 years in the past. Soon, for the same reason, Alexander the Great claimed he descended from the Pharaonic line of Nectanebo. You can detect other nifty objects in the background.

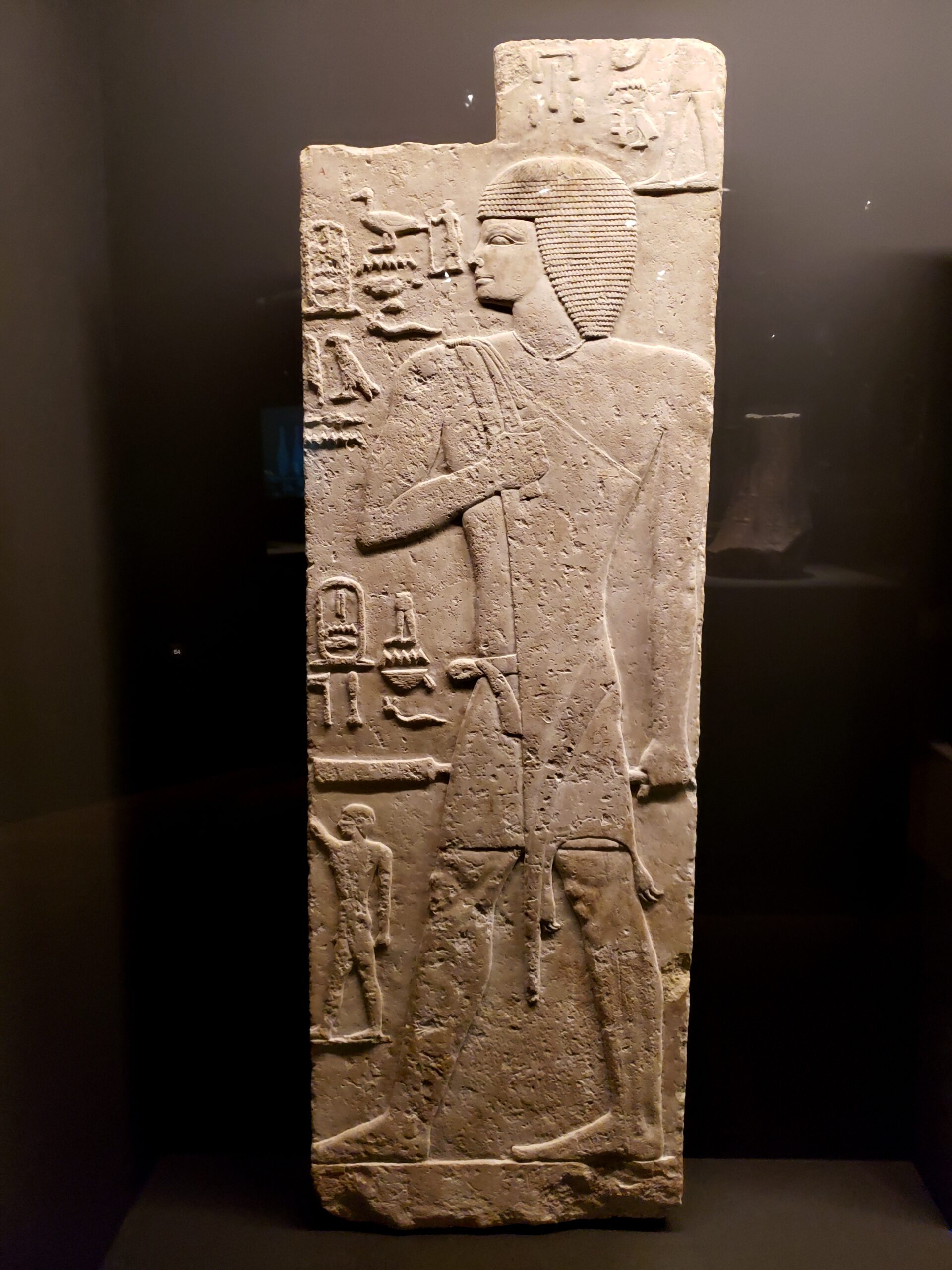

(27th century BC) One of the most elegant of the bas-reliefs on display, this wall segment from a tomb remembers the dead priest of a cult dedicated to King Sened, from a much earlier time. As with Sened, religious cults arose in the name of the most renowned Pharaohs, devoted to keeping their memories – and powers – alive.

(14th century BC) The fame of Nefertiti, Akhnaten’s queen, spread through the west during the 20th century based on the idealized imagery discovered In their tombs. As the exhibit illustrates, she became a model of beauty, of style, of female empowerment, and more. This stone engraving from her time shows her with her characteristic cone-like headgear, but with perhaps a more realistically African beauty.

(2013) Even today we choose to walk the walk and talk the talk of an Egyptian, as we see fit. On this poster, Nefertiti – who rebelled against the worship of multiple gods – is refashioned to be as rebellious as a commoner during the popular Egyptian revolt of our time. The exhibit shows both serious and hilarious illustrations of such appropriation of royal Egyptian imagery.

(14th century BC, modified in the 13th) This splendid lioness statue of Sekhmet, goddess of destruction and healing, comes from the reign of Amenhotep III. His later successor Rameses II transformed this and other monuments by replacing his predecessors’ carved names with his, so his memory would more likely live on.

(19th century BC) This is quite a sculpture of another famed Senwosret from Egypt’s flourishing early period: even in miniature, he seems firm, calm, and seemingly wise. This pharaoh oversaw a wide empire that reached into modern Ethiopia, where this obsidian came from. The Gulbenkian Museum itself owns this beautiful figure.

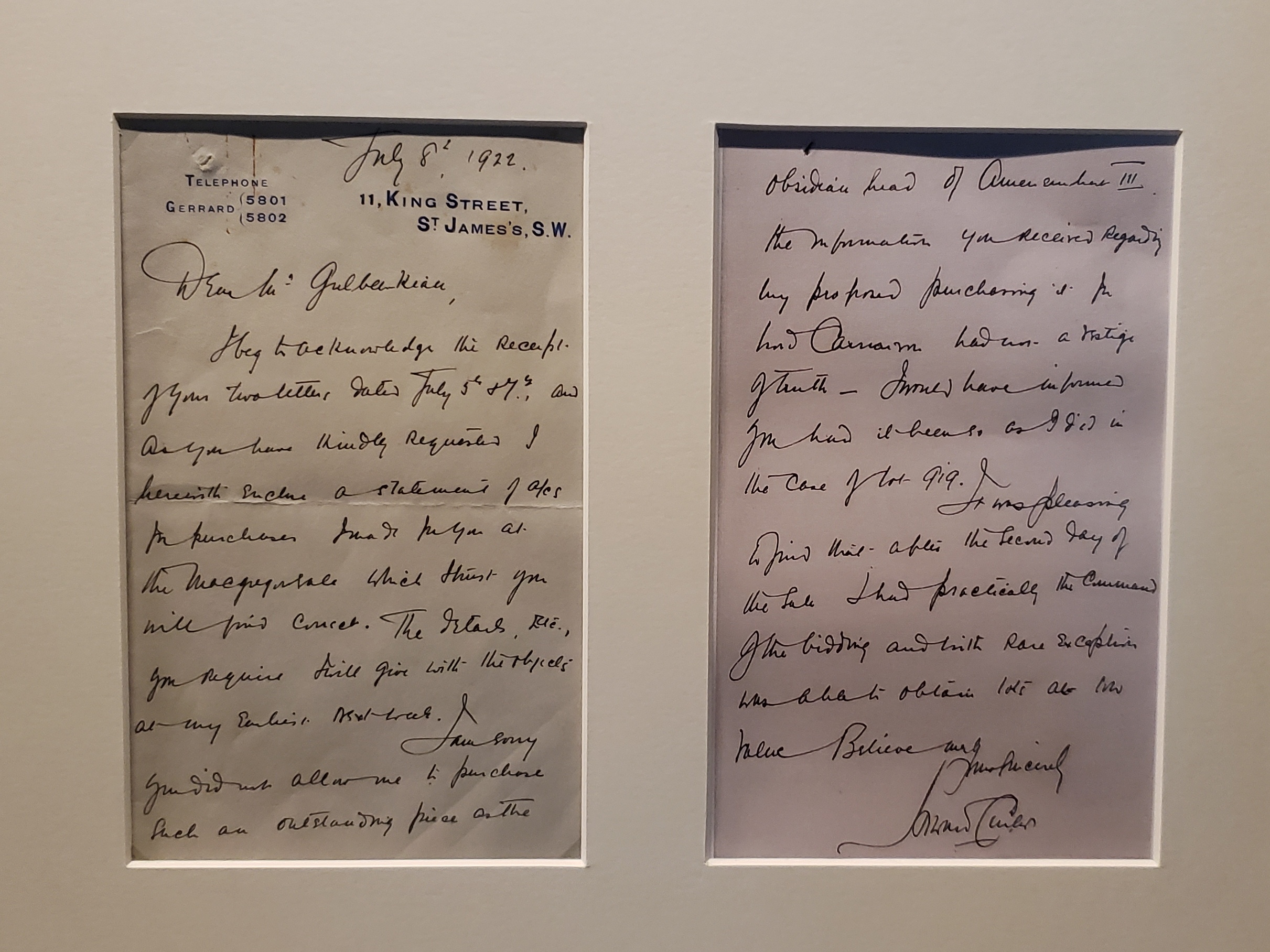

(1922) Calouste Gulbenkian loved Egyptian history and art, so this exhibit fits the museum well. You can marvel at what he gathered in its permanent collection. As this letter shows, back in 1922 he had hired an Egyptologist to advise him on acquisitions. That person was Howard Carter who, the same year, discovered and explored the tomb of King Tutankhamun, unearthing the treasure trove of objects that astonished the world. A few months earlier, in this letter, Carter lamented to his employer how much he regretted his failure to buy the obsidian head of Senworset (as seen in the prior photo). It seems that Gulbenkian had already bought the piece.

(As early as 16th century BC) Ever wondered if your prayers were heard? Fret no more! Priests would place these ceramic “hearing aids” near statues of gods or kings to help ensure someone is listening.

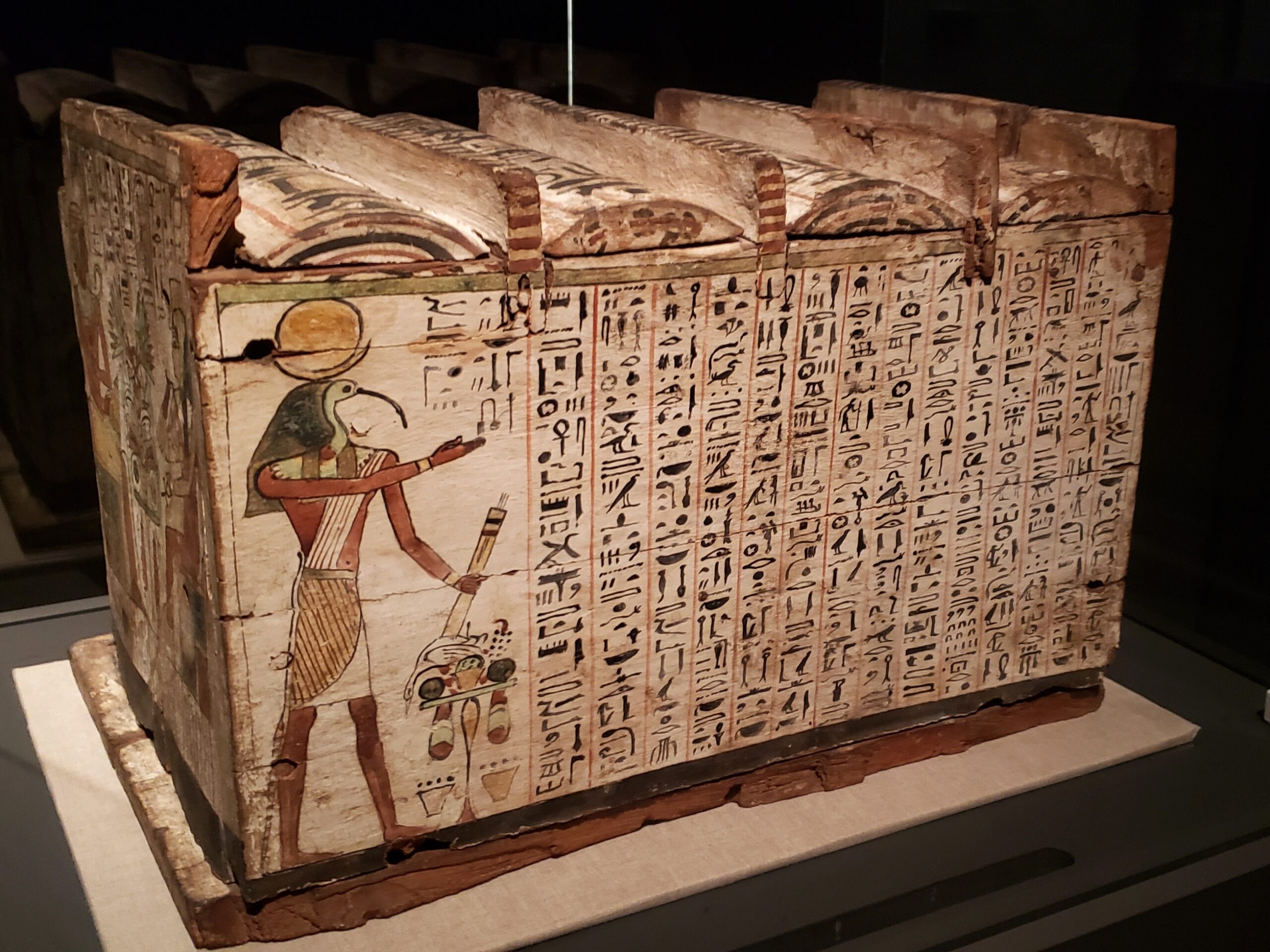

(As early as 11th century BC) That such a wooden furnishing for a tomb survived is pretty much a miracle in itself. Perhaps it effectively evoked the aid of Amenhotep I and Ahmose-Nefertari whom their painted images memorialized some 400 or more years after their reigns.

(14th century BC) Some rulers are best forgotten, it seems. An iconoclast hammered out the names of a dead ruler from the past on this memorial stone. Similarly, as the exhibit shows, leaders often tried to efface the memory of pharaohs like Akhnaten, for their heresies in his case, or perhaps bad leadership skills in other cases.

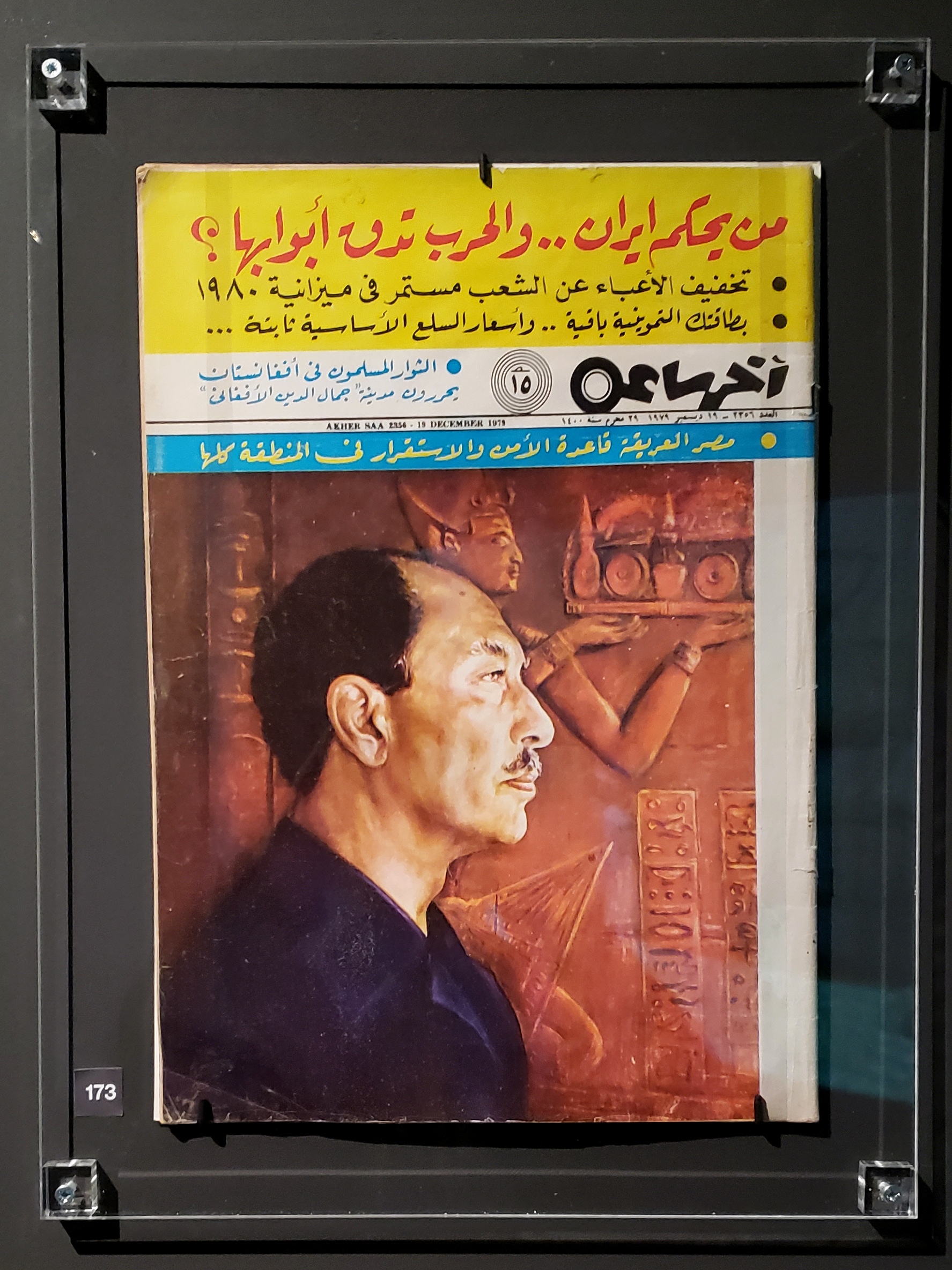

(1979) In this journalistic piece, Anwar Sadat is praised in words and images for following in the footsteps of Rameses II, who was said to have made the first peace treaty ever with the Hittites. Similarly, we learned throughout the exhibition, Egyptian pharaohs of several millennia earlier aimed to be compared with famous predecessors.

(1933) Though Tut, Nefertiti, and Aknaten captured popular imagination from the 1920s on, “age cannot wither” Cleopatra, as Shakespeare wrote. The exhibit shows the many ways she has been memorialized in the western world across centuries: as a dangerous temptress, a sex object, a fallen woman akin to Eve, a heroic figure choosing death instead of disgrace, a feminist icon, and a defiant black woman. Yet, in all incarnations, a dazzling beauty. Among the examples of the highs and lows in our retelling of her tale is this 1930s ad which sees Cleo as a modern woman who knows what she wants, including fabulous clothing. And what she wants is Cleo Cola.

As for us, we didn’t want to leave the show!

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Portugal, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)