The custom in Jewish cemeteries is to place a pebble, or small stone, on the headstone at a grave site. In doing this, you affirm you remember the dead. It’s a custom that might have derived from the roughly heaped cairns constructed to mark a grave in the past, piles preserved by adding to them.

In our emotional journey to Ukraine, the land from which Barry’s grandparents emigrated at the beginning of the 20th century, we placed stones to honor both those who had departed alive and those who remained in the ground. The difficulty was finding tombstones on which to place a stone of remembrance. Some had been preserved by townspeople who collected them into new, protected cemeteries; some had survived hidden over time by thick forest; most had been broken up into shards of stone, then vanished under cattle grazing fields.

We had also hoped to find other remnants of their lives – homes, synagogues, records, people. Few of these survive either: the thriving shtetls, or peasant villages, reduced to a few buildings or vanished into dirt; just a synagogue or two standing still because they had been useful as storehouses.

Mostly we found mere echoes and absence.

Our visit centered on a small part of the Khmelnytskyi region, about two hundred-fifty kilometers east of the Polish border. Our guide, Maxim, hired for us by a very helpful landlord in Lviv, was just the person we needed. He was a student of Jewish history in Eastern Europe, an expert in old cemeteries and gravestones, plus an ardent protector of that heritage in Lviv. (For more of what we saw in Ukraine, click here to read the article, A Ukraine to Remember.)

As we drove to the interior, we discovered that our ancestors had chosen a bountiful countryside. The mainly flat plains we passed through had long been ideal for growing crops and raising livestock. Their villages were the market trading and social centers that served the farming population.

Along the way, we stopped at Brody, the only large town around, for a good Ukrainian lunch of pierogies, Russian-style salads, and other local fare. In the late 19th century, Brody had been the border between Poland and Russia, which controlled Ukraine then.

As Maxim explained, our relatives would likely have trekked here to flee the pogroms and economic troubles of Russia to the hope of the west. Trains ran westward from Brody to Lviv, and then onward to the northern ports of Germany and Poland where ships departed for America.

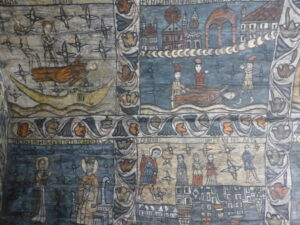

Brody’s Jewish community would have welcomed emigrants like our ancestors on their passage west. And, across a rag-tag park near the restaurant, we discovered a synagogue collapsed inward as if it had been bombed. We could still detect old markings and inscriptions near the crumbling tops of those walls still standing, but not much else from that time remained.

Earlier we had passed through a much smaller town that had been a peasant village a century ago. There, Maxim had pointed out a derelict warehouse that also had been a synagogue, before it was used for storage and finally abandoned. We began to understand how little of the past we might find intact at our destination.

Our home base for our visit was Shepetivka, one of the villages we could trace to our family and the only sizable town in the vicinity.

A cousin of ours had visited Shepetivka twenty-five years earlier. But we realized that more than a hundred years had passed since anyone descended from Barry’s great-grandparents had seen the other two villages where they lived.

One of these was Nova Labun, once known as Lubin, a hot dusty hour’s drive from Shepetivka. Nova Labun was hardly more than a couple of crossroads and a cluster of well-kempt buildings of indeterminate age, though some might have seen the early 20th century. A horse-drawn cart clopped by as if we had gone back in time.

An official at the modest town welcomed us warmly. She was quite excited that we were visiting the town and showed us around its museum, several rooms housing an assortment of artefacts and photos from the last hundred years or so. Though the museum displayed some fuzzy photos of farmers and tradespeople from the period when our ancestors lived there, none of them seemed to depict the local Jewish community.

A quarter mile away we wandered a large flat area that had been the shtetl marketplace, according to Maxim and our museum host. In one direction, it dropped off toward the river and, in the other direction, at the edge of some woods, stood a long one-story arcaded structure that had long been falling apart. In between, a single stuccoed building, like a farmhouse, looked in much better shape. Several dirt lanes crossed this expanse, wandering off to nearby fields.

The open fields down toward the river had been the Jewish section of town and the long, decrepit building was likely one that had been used for trading. The homes themselves had disappeared, deserted in part because of Russian pogroms and later destroyed by Nazi forces. Here too the town synagogue had sat, also destroyed in World War 2. All traces gone.

The helpful woman at the town hall had also directed us a bit farther out of town to the site of an old Jewish cemetery, tucked away near a couple of Christian ones. At first all we found was forest, though a stooped farmer passing by directed us to the right spot, “Up there,” she pointed.

One of us spied some shards of old gravestones peeking out of the fallen leaves and branches, so we started up the hill before us. Slowly, picking our way up through the trees and debris for over an hour, we came upon dozens of other gravestones.

Most were typical slabs; others had elongated stone tails or pedestals intended to steady them on the ground – an unusual style of marker used in this region. There were plenty of broken pieces, but most of the headstones had naturally settled into the soil over the last century or been pushed over forcibly.

At each one in good shape, we tried to decipher the inscribed names, just in case one of those names was familiar. Maxim enthusiastically interpreted the iconography and formulaic testimonials – such as a Sabbath candlestick for a woman, Star of David for a man.

Yet, while the tombstones seemed to date from around the end of the 19th century, none of them held names we recognized.

There was even less of the past to see at the other town of our relatives, Bilohorodka, a slightly larger village with a residential school at the gathering of a couple of local roads.

At the center of the village, a few rehabilitated houses and open fields were all that remained of the original shtetl. Maxim ventured onto the school grounds to locate the site of the old synagogue.

One of the teachers questioned us and then brought out the school’s headmaster. He exuberantly reviewed the history of the town, hardly slowing down to let Maxim translate for us. Most of the Jewish population, he explained, had left for Palestine or the west by the 1920s; few of these ever visited in the years since. And those who remained later were removed to the concentration camps.

The synagogue had occupied the space we stood in, now an athletic field. Slight berms that defined the foundation of the destroyed building were still there. The Jewish school had been In the open space over by the trees.

We apparently were a curiosity ourselves. Like a good host, the headmaster took us into the school for some tea, and showed us a display of the notable people who had lived in the town, including a well-known Ukrainian writer. We told him of our experience so far.

In his office, he and the English teacher presented us with cloth bracelets that the children had made. He wanted to continue to talk, but we knew there was little here of what we had come to see. After a polite interval and many thanks, we said goodbye.

At the edge of town – atop a hill amid grazing cattle and open fields, and occasionally under the curious gaze of local farmers passing by – we found traces of Bilohorodka’s Jewish cemetery.

We could just detect rows of former gravestones from a set of bases that remained visible on the ground. Fragments of other stones were strewn about haphazardly, blown up either by the Nazis during the war or by the Russians. Somewhat miraculously, a handful of headstones still stood, half buried in the dirt by now. Here too we could not identify any familiar names from the few inscriptions we found. But, in memory, we placed small stones on the most distinctive marker remaining.

Back at Shepetivka, there were two other cemeteries. One was also a large grassy field, similarly strewn with stone fragments, plus some scattered pedestal monuments askew on the ground. There were few headstones left that were at all decipherable.

The second cemetery was near a woods across the river, next to a popular swimming spot crowded on a hot day with local children and supervising adults. Hundreds of tombstones for people of various religions had been moved here to preserve them and to create a kind of memorial, though not a well-kept one. Some stones had already been overrun with bushes and wild growth. We looked about for a while, but knew we would have little chance of finding a familiar name, or even headstones from the period we were interested in.

Before we left, we looked across the river at the town, with a view mostly filled by industrial buildings. We had seen this view in an old photo included on a website recalling Ukrainian Jewish heritage, a view dominated by the old synagogue high on the bluffs. That building was still there, just peeking over the treetops and newer buildings.

We had hoped to visit the synagogue, where some of our relatives must have prayed, though little would have been the same after all these years and its many uses since, including as a non-religious school. Even the exterior had changed from the past.

Nonetheless we had tried to get in touch with the few remaining Jewish members even before we came to Ukraine. We never heard from any one. So we had to be content with looking at the closed two-story building, a portion of which that small group was now using. We still felt the power of it, gleaming white, the Star of David quite clear on its large pediment. And still so solid compared to all those bits and pieces of the past we had struggled to find.

Before we headed west back toward Brody and Lviv, following the route our relatives had taken a hundred years earlier, we searched out another memorial, a somber reminder of what happened to those who stayed here.

It commemorated a dark night toward the end of World War 2, when the Nazis trucked most of the local Jewish population to this spot and killed them all. Like a bad memory, the tribute was hidden away down a barely discernible path off the main road. In that place, treading quietly amid the tall trees of the shadowy forest, we all turned somber at the memory of so much slaughter across Europe during that time. And yet relieved that so many of our ancestors and other villagers had evacuated the area years earlier.

In the end – amid the broken stones, wrecked synagogues and dust – we mainly found echoes and absence rather than tangible reminders of family history. But at least we touched the ground our ancestors walked on.

When alive, they only looked back to welcome their brothers, aunts and other relatives who followed them west. With some broken stones, we looked back on their behalf to pay respect to the buried relatives whose mostly unmarked graves they left behind. We mourned the displaced, oppressed and exterminated.

And we glimpsed the life they abandoned so they could make new chances for themselves…and for their descendants.

(Also, for more pictures from Ukraine, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the Ukraine itinerary page. To see a larger view of any photo, just click the image.)

I loved this. Thank you. Now that I have your blog, I will be checking back in. Safe travels, you guys.

Always a pleasure to have people reading in their armchairs! Thanks!

Wish I had known you were going. My mother’s parents lived in and near Br’chan or Brichan, which I suppose to have been a very similar place. My grandmother recalled playing, as a child, in what she called “the Turkish cemetery” there–must have been an Ottoman outpost. The drift of tribes and time continues across all the world in an order no one understands, and each generation seems only to want to obliterate the work of its forbears.

We weren’t even sure we were going until just before! So many of us have family stories from this area. The Brichan I found on the map is at the edge of Moldova, though borders were fluid back then, about 300 kilometers from where we were (or 5+ hours drive). It eemed to be a fairly large town by the late 1930s, according to its records at jewishgen.org. Until the Austro-Hungarian empire took over from the west in the late 19th century, and Russia from the east, much of these lands was quite tolerantly Ottoman controlled. Even after, as in Sarajevo, many Muslims likely remained alongside the Christian and Jewish populations. Nationalism in the late 19th and early 20th, along with the collapse of imperial power centers after WW1, fired up antagonisms that fed WW2 and ethnic rivalries.

Barry:

Just found this blog post. I visited Ukraine and Labun/Lubin/Yurovshchina (the community of my paternal family) in the summer of 2013. I have been researching Jewish families from Labun for several years and have been blogging about my research. I would like to know more about your family. You may see posts from my Ukraine visits at http://extrayad.blogspot.com/p/ukraine-visit-2013.html

I also have a webpage about Jewish Labun/Lubin: http://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/yurovshchina/index.html

Emily

How wonderful for you to reach out on our common connection. I will be in touch soon!