Ten thousand years ago, in a region where currently Mozambique, Zambia and Malawi meet, members of the Batwa pygmy tribe recorded important features of their life on the rock walls of their shelters. Unlike other early tribes of Europe, where temperatures got a lot colder, these natives did not need caves, but sheltered beneath massive overhanging rocks and escarpments.

In this way, they were protected from the hot suns or seasonal rains, and from aggressive enemies. The overhangs – common formations within a small range of boulder-strewn mountains stripped over time of dirt and most vegetation – were defensible since they loomed over the plains, as we discovered while scrambling up the hillsides.

When not hunting, gathering fuel, or cooking, the pygmies practiced home décor by drawing pictures on these walls. The intent, it seems, was to tell tales explaining the world, to pay tribute to the natural world that sustained them, or illustrate important cultural lessons.

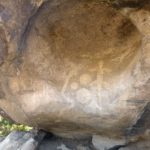

Their canvas was rock; their paint was a mix of mud, blood and other ingredients, whose reddish combination preserved some of their decoration till now.

What survives at a site now called Mphunzi is mostly primitive and geometric in fashion, with grids and lines marked with fingers – some in the shape of ladders, the way these short people climbed to draw figures a bit higher on the wall. Circles and ovals suggest pots or stools. These also might be connected with rain-making and fertility concerns.

They drew abstract figures for some creatures, such as millipedes and reptiles, as well as what must have seemed to them an impossibly tall animal, a giraffe. They also made surprisingly realistic images as well. One partially visible giraffe painting shows the animal bending its long neck toward a waterfall to drink.

Soon a new tribe, larger in stature and stronger, drove the pygmies away. These were the Chewa people, who occupied most of Malawi over the last several thousand years. Their language Chichewa is the official native language here.

The Chewa occupied these same rocks. They painted on these same walls, at more than a hundred sites in the area together designated as UNESCO World Heritage, but in far different ways.

First, they painted with white clay, so their paintings survive as white figures.

Second, as farmers, they lived in the plains, not the rock shelters. So, most importantly, they considered the stacked boulders and rocky formations a sacred place, fit for art that reflected the secrets and rituals of their culture – especially women’s rites like the celebration of girls into puberty, rain-making and funerary practices. The initiates into those secrets – men or women – formed a spiritual society called the Nyau, a cultural bond still active and mysteriously held close after all these years.

The last difference is that the figures at Mphunzi and the adjacent Chongoni site, by contrast with the pygmies, corresponded to the mythical and symbolic animal spirits who controlled various aspects of life, and who were featured in ceremonies as masked dancers. We heard that such rituals still take place at these boulders.

This connection across thousands of years fascinated us. Fortuitously, after viewing the rock art, we were able to visit the charming Kungoni Museum nearby at Mua and tour an extensive display of these masks, of which over 200 different figures have been documented. And we could read seemingly endless explanations of the tribal rituals surrounding the critical junctions of life – birth, puberty, marriage, chiefdom/leadership, and death.

We also had the chance, at a demonstration by a troupe fostered by the museum, to see some of the masked figures dance a bit of their Gule Wamkulu, the “Great Dance of the Chewa people,” the heart of their religious rites and a UNESCO-recognized cultural heritage as well.

Sometimes the masks were animal to take on the special qualities or import of that animal. These figures are most clearly connected to the Chewa rock art, as they appear most frequently on the walls. The repeated drawings of lizards, for example, tell of its role as messenger between heaven and earth, delivering news of death’s finality on earth, but with the potential for ascent to another state.

In one concave, frame-like hollow, several lizards dance to the accompaniment of sun and stars, a clear indication of the larger importance of these figures.

On another wall, we can see an elephant accompanied by guardian figures. In rituals, the elephant mask represented those who were elevated to chiefdom, and appeared typically as the climax of a ceremony, as, let’s face it, it is tough to top an elephant.

Other typical masked figures do not seem to appear on the rock walls.

Some are divine or supernatural. The final dancing figure we saw at the demonstration looked like a two headed llama, but represented the womb and the cycle of life, from birth to passage elsewhere via the grave. Through it, the dancers invoked spirits to ensure good fortune in that cycle.

Most notable of the divine figures in the masked rituals were Chazunda, the wise ruler and guide of ceremonies, along with his wife Maria, mistress of female initiation rites. Their presence together provided a model to the tribe of good marriage bonds. Other figures channeled the spirit of different gods or ancestors to deliver other lessons.

Also not present in the rock art, more mundane human figures appeared in the dances over time either as social lessons, or as wry commentary on daily life. In the dances we saw, a drunken villager and a wife-beater harassed the corps of dancers to underscore the social evil brought by his actions.

In a more contemporary ridicule, a dancer in a Chinese mask reflected resentments against trading practices by Chinese store-owners.

It’s not clear how widespread are the religious and ritual practices today, though Nyau is apparently strong in spirit. Modern life-styles have chipped away at the old traditions. And for hundreds of years, missionaries and their new religion aimed to transform or eliminate traditional religious practices of the local tribes.

So it’s ironic that the effort to ensure the survival of these traditions and the power of the Nyau secrets – through the museum and the dancers – are driven by a Canadian priest at the Mua Mission, Claude Boucher Chisale.

And he has fostered a successor art to the rock paintings of the Chewa people. Since the mid-1970s, local artisans have developed a sophisticated wood-carving culture, depicting both spiritual and everyday themes. The museum and its small hotel display the richness of that art, with splendid masks on display and dancing figures even on the toilet paper holders.

Inside the main building of the museum, a richly carved wooden screen of daily life is a visual splendor. Next door, the gift shop offers extraordinarily complex and beautifully carved panels and sculptures.

And in the elegantly unassuming church of the mission, a few steps away, you can follow the traditional stations of the cross through lovingly executed carvings. The artisans sublimely simplified each panel to the essence of the narrative, using at most three figures – all of whom are clearly native Africans.

(Also, for more pictures from Malawi, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)