As with many cultures, experiencing Armenia’s spirituality means going to high places. It’s the way we started and finished our visit to this wonderful country – by ascending to the mountain tops where World Heritage monuments and landscape continued to take our breath away.

We began with one of the most important of Armenia’s monasteries, Haghpat, a model for many of the rest.

The view from the monastery at Haghpat. Sanahin these days is encircled with buildings that block the valley view.

Perhaps, in the 10th century, Armenian Queen Khosravanuysh knew that the monasteries she founded would endure. Certainly she believed that her Christian faith would last, as well as the scholarly work of its monks. So her buildings were constructed with huge blocks of local basalt and massive stone supports – per legend, “akh pat” or strong wall.

The main church at Haghpat, essentially a cross in shape with the dome at the center, showing off its solidity and permanence. It’s one of many surviving buildings in the complex.

And she insisted on carving the enduring images of her sons into the sides of the Haghpat and Sanahin churches where, to this day, the sons of the queen still deliver up the buildings.

Across the hills and gorges of northern Armenia, many medieval churches have suffered misfortune, broken or needing modern fixes. But the Queen’s legacies – the complexes at Haghpat and Sanahin, and the works of her monks – survive, little touched by time, as notable World Heritage sites.

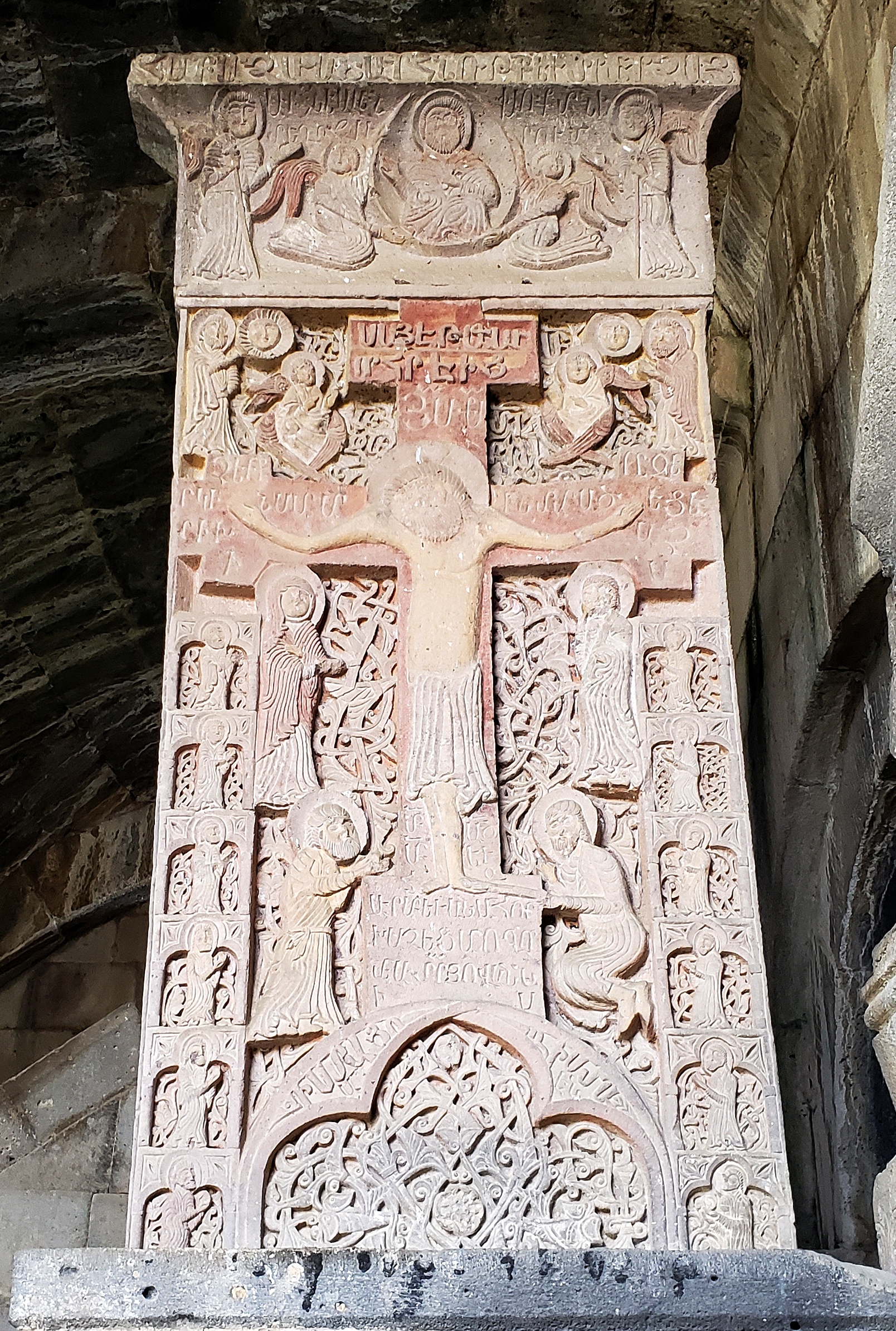

Many khachkar – crosses elaborately carved on stone slabs crowded with geometric decoration – adorn Haghpat and Sanahin. One of the great treasures at Haghpat is this unusual 13th century one that includes Christ on the cross attended by saints and angels in a very emotional representation, the so-called “Amenaprkich” (All-Savior) cross. He seems to be embracing his heavenly fate and also giving up life.

A more typical, but still intensely decorated khachkar, stone cross.

Ornate decorations and Armenian inscriptions at this entryway invite visitors to the Gavit, or entry hall to the church at Haghpat. You can just see to the right and left a kind of medieval graffiti found all over the exterior: crosses of various styles carved into the stones.

The Gavit or narthex of the Haghpat church, with its unusual double vaulting, meeting not in the center, but around an ochre-colored dome to bring light within. Other buildings at the Haghpat complex imitated this feature.

A particularly notable ceiling at Haghpat appears at the 13th century addition called Hamazasp. To us the incised corners and the abstract floral decoration of the dome seemed Islamic in origin.

Apse of the Haghpat church with 13th century fresco of Christ enthroned in heaven, plus other scenes. Well preserved frescoes like these are unusual in these old churches.

At Sanahin, three pitched rooves and six arches form the entryway to a gathering hall linked to the church, whose conical roof rises in the background. Two splendid stone crosses, khachkars, also grace the entry.

The three barrel vaults of the gathering hall at Sanahin are nearly overshadowed by the stark beauty of its pillars. The floors of this hall as well as those of the adjacent narthex to the church are covered with stone slabs memorializing those buried in the crypts below.

Columns like this at Sanahin, wreathed in Armenian script, just say strength. Rows of these supplement the arch system of support.

Long library hallway at Sanahin with niches for reading and reflection.

In the south, in the sumptuous landscapes near Yerevan, we ascended to other centers of Armenian spirituality.

Along with the noted World Heritage monastery of Geghard, east of Yerevan, the upper Azat Valley is included in the World Heritage designation. You can see why.

The monastery of Geghard, east of Yerevan, is tucked into the upper Azat Valley and partly carved out of the surrounding rock. The 13th century church you see today originated back in the 4th century. The name means “spear,” because, from the 4th century, it sheltered a piece of the spear that pierced Jesus’s side.

Not only is its complex set of chambers and chapels full of decorative detail, but the monastery holds a special role in the preservation of Armenian manuscripts and religious history. Many hermit caves peak out of the mountainsides, as well as huge stone carved crosses.

The narthex, or gavit, of Geghard church with its splendid stalactite vault and open dome for light, supported by four very sturdy columns.

Decorative detail from the family chapel and mausoleum of the Proshyans, added to the Geghard church by carving the space out of the rock in the late 13th century.

On a second level of Geghard, also carved into rock by the Proshyan family in the late 13th century, is this simpler tomb and chapel. Oddly, a porthole toward the back lets you look down at people in the other Proshyan chapel below. This large space takes the form of a traditional open entryway/gavit with a domed roof arching over its support columns. But the greater pleasure is hearing its resonant acoustics, as this small choir demonstrated. Turn up the volume…

Below nearby Garni Temple, this gorge plunges into the Azat Valley. Way down there, in the center, you can find walls of those unusual hexagonal basalt pipes often formed from volcanic action.

Dedicated to the god Mithra – the sun that defeats the dark – this late 1st century temple stands along the Azat Valley, itself a UNESCO designated area to the east of Yerevan. The temple is made of bluish basalt stones held fast by metal pieces, not mortar. The top is especially notable for the artistry of the decorated borders and figures. What you see is a remarkable reconstruction of the building that collapsed in the earthquake of 1679, using original pieces and construction methods.

Between Geghard and Garni in the valley are several other medieval monastic churches like Saghmosavan and Hovhannavank, each perched high above their own part of the abyss.

This is what remains of Zvartnots, another World Heritage church from the 7th century, soon after Armenia adopted Christianity as the state religion. It’s strictly not on a mountain, but constituted a mountain in itself. The tall columns only hint at the scale. Its outer circle was a 32-sided polygon, some 40 meters (130 feet) in diameter. Above that rose two other cylindrical levels, including a domed peak topping off at 45 meters high (150 feet).The Holy Roman Emperor of Byzantium himself came to the inauguration, and wanted to copy it. But just three hundred years later the massive structure collapsed either by earthquake or attack.

The famous capitals of Zvartnots, the massive 7th century cathedral destroyed by an earthquake, display splendid flying eagles flapping around the hexagonal stone.

Back up north, near Haghpat and Sanahin, at the edge of bottomless Debed Canyon, swirling with clouds this day, the huge church at Odzun in the north of Armenia dates originally from the 6th century.

But to us, the 10th century Akhtala Monastery and Fortress towered above most other Armenian churches because its sumptuous and quite rare 13th century frescoes have survived.

Peering down over deep canyons in the north of Armenia, the walls enclose a cemetery filled with khachkhar stone crosses and a peaceful garden, as well as the large church itself.

Every wall of the cross-shaped church at Akhtala Monastery – as well as its arches and corner niches – glows brilliantly with 13th century frescoes. This detail from the west wall calmly presents Mary enthroned, beneath heavenly scenes like those in the windows. To her left, saints and the saved come marching in.

The 13th century frescoes from Akhtala Monastery also include biblical scenes like these from the New Testament. Above, Mary hovers protectively, while God seemingly takes the podium, and saints round out the scene.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Armenia, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)