In brief: The remote pair of monasteries at the World Heritage sites of Suso and Yuso draw pilgrims en route to Santiago and Spaniards honoring their language’s roots.

Amid all the religious sites – and wineries – of the western Rioja region of Spain, one World Heritage monastic site is pre-eminent, especially for Spaniards. It is twice blessed, in a sense.

The most famous blessing happened around the year 1040 in the medieval monastery.

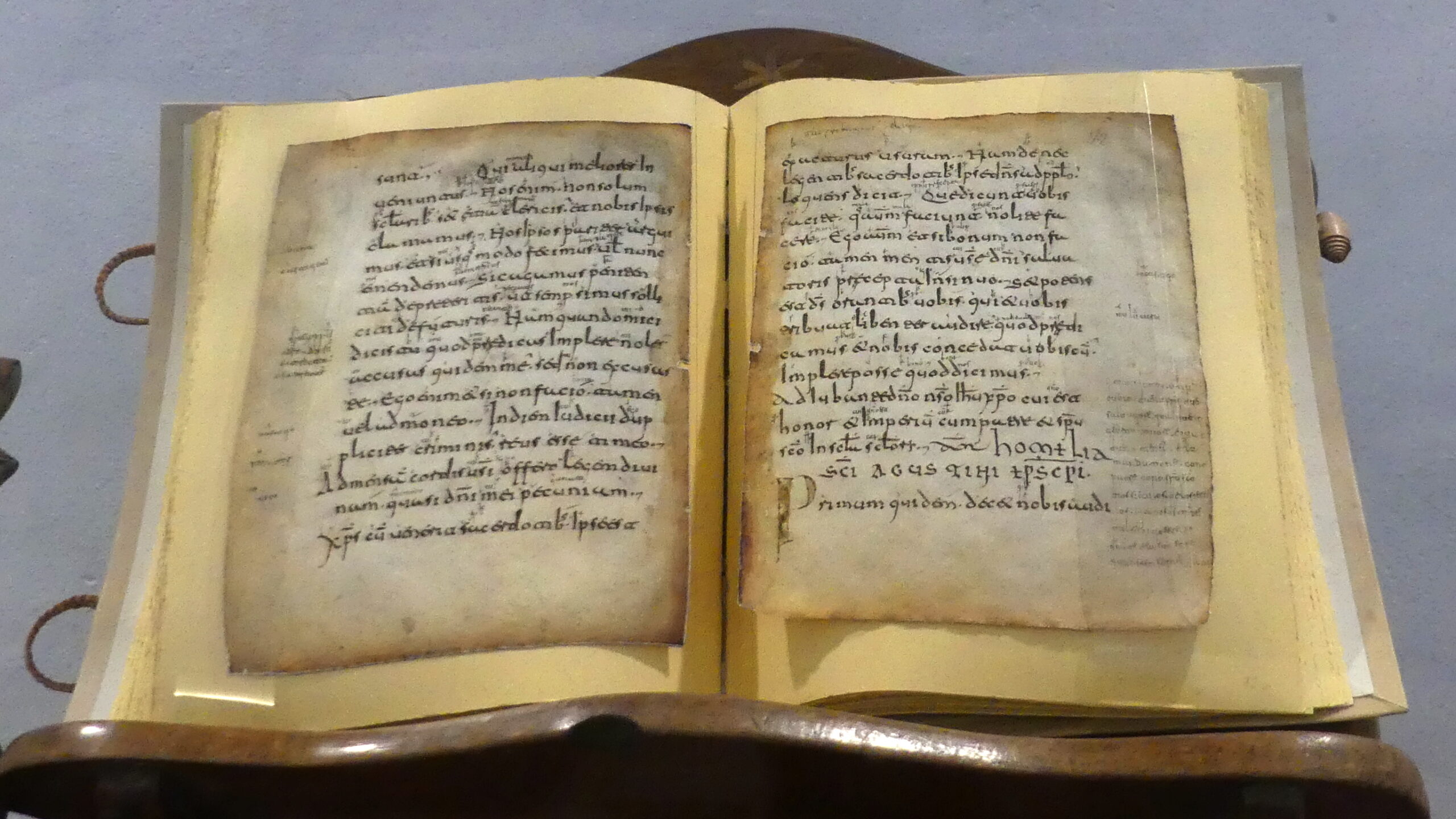

An anonymous scholar was wrestling with parts of a Latin text. So he penned some notes in the margins of the codex he was reading, using the “vulgar Latin” of the region, what we now recognize as Castilian or Spanish. Because no prior written example of the language exists, San Millan is considered the fount of the Spanish language.

Visitors are treated to this display copy of the famous annotated codex, Aemilianenses 60, with the scholar’s Castilian glosses next to the Latin text. The same codex also recorded the Basque language for the first time.

The second blessing was what led to the first.

In the 6th century a hermit – Saint Emilianus, or San Millan in Spanish – took up residence in a cave, soon attracting enough followers to found a monastic community on a hilltop called Suso (from ‘up’ in Latin).

The monastery of Suso, a steep climb (or 5 minute bus ride) up from the new monastery, became a pastiche of styles that reflect the evolution of hundreds of years, with Visigothic arches and Muslim influenced Mozarabic renovations into the 12th century. Notice the cave for other hermits at the right center.

This gives some idea of the hermit’s view from the site of Suso, the medieval monastery. Much of the land nearby has been cultivated, for wine and other products, so surely looks different from San Millan’s 6th century viewpoint. But we too delighted in the green of these hills, what with the arid conditions of so much of the area due to drought.

Inset in the stonework of Suso’s entryway are the tombs of three queens who are featured in an important early Castilian poem. Those look like seating, rather than tombs, but this is the crypt for their guardian.

Marked by a simple, but elegant Visigothic arch wiithin Suso, this cave was the original burial site for Emilianus. It’s adjacent to a similar niche where he once lived. The monastery was progressively built around and above the caves. A roughly carved but eloquent life-sized image in black alabaster honors the saint, but his body was moved from here centuries ago.

This holy place thrived during the Middle Ages, when that enterprising scholar labored at his studies. In the 12th century, however, Emilianus’ body was set to be reburied in another place. As the story goes, the oxen pulling the cart stopped a bit lower in the valley from Suso, sending a sign from God according to the king. A Romanesque monastery was built there, to be replaced in the 16th and 17th centuries by the current structure called Yuso.

These superb 11th century ivory plates, which retell Biblical stories, lined the box with the remains of San Millan. Napoleon’s troops had the chance to take the panels as they pillaged the monastery in the early 1800s, but did not value them sufficiently. They did, however, destroy the box and some pieces of the saint went missing. This box – with the rest of him – dates from 1944.

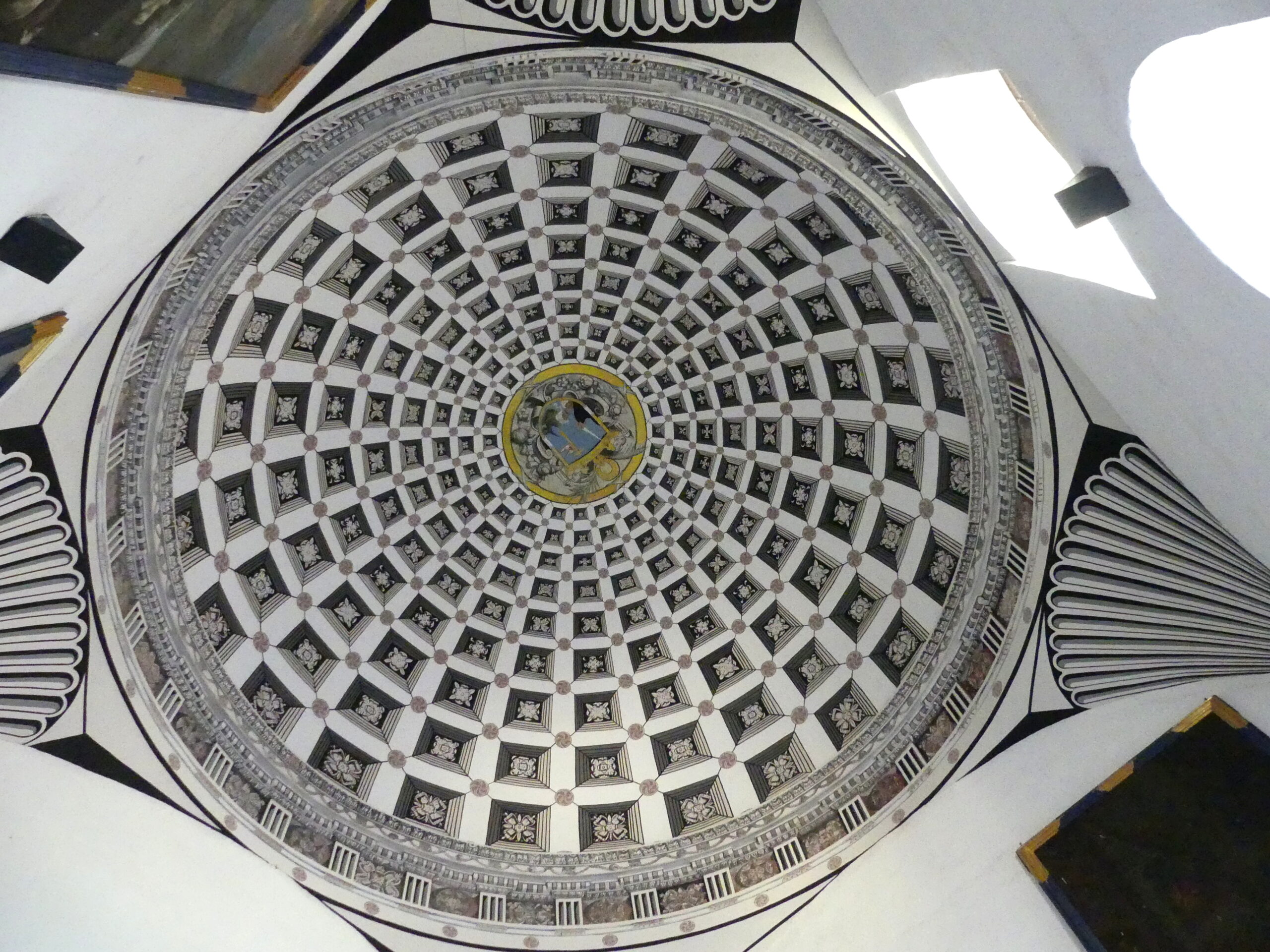

The newer Yuso monastery at San Millan de Cogolla includes a quite beautiful church with many spectacular features. Many paintings tell the story of Emilianus’ holy acts. Among the most unusual features, though, is this delicately decorated sacristy. The 18th century frescoes include depictions of saints and seasons, contrasted harmoniously by painted gold details. Miraculously and scientifically, there has been no need to fix or restore these paintings in four centuries. The alabaster flooring controls temperature and dehumidifies the room so the climate is ideal.

This view from the choir section of the church interior at Yuso shows the mix of Gothic style and Baroque decoration that evolved over the years. In the center of the choir, a large rotating stand held the 20 kilogram songbooks, with pages big enough for every singer to read from afar.

In a room to the side of the upper choir, the song books are still stored in old wood shelving with sliding trays. They have been remarkably preserved because the shelves are ventilated through alabaster-lined walls, again removing humidity.

One of the last delights we saw at the new monastery was this mind-blowing vault over the main staircase.

Before we left, we enjoyed some drink and tapas at the mission café, gazing at Yuso’s 16th century exterior, tucked into the hills of the region. It’s at the edge of a small village of narrow streets, a long way from major roads or cities. That makes this a more challenging side trip for the travelers on the way to Santiago de Compostela.

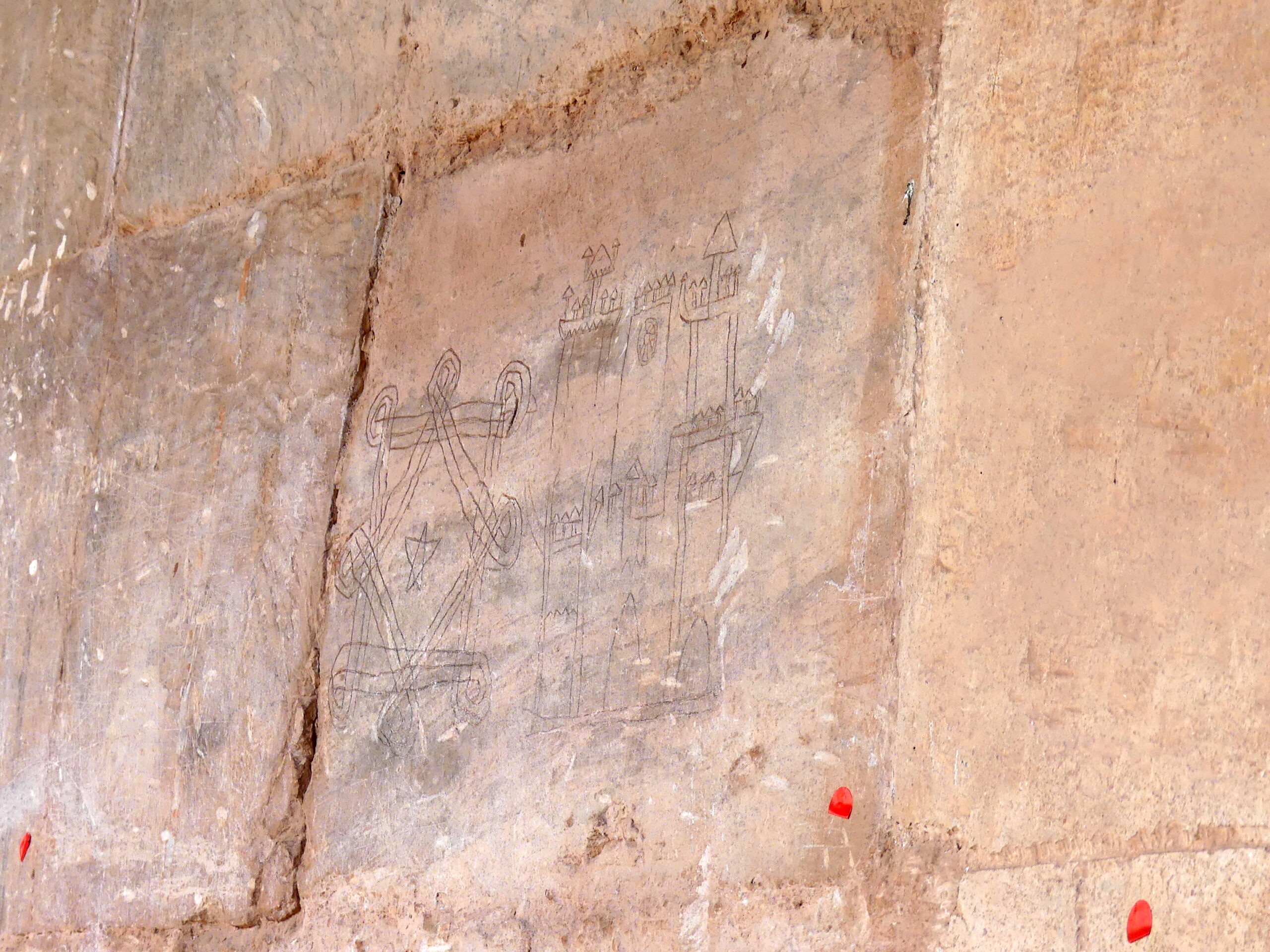

Occasionally over the centuries, pilgrims along the Camino have even made their mark on the walls of the entryway to revered old Suso. Some of the oldest and most interesting, like this graffiti, have been preserved.

We saw many of today’s pilgrims along the way, and the marked pathways they use. Fortunately, the tiny town – like so many others on the Camino – is well stocked with hostels and inns.

The pair of monasteries at Suso and Yuso draw crowds of Santiago pilgrims from around the world along with reverent Spanish speakers.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Spain, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)