In brief: In northwestern Zimbabwe, Matobo National Park offers three unusual experiences: rhinos, Cecil Rhodes, and awe-inspiring landscape.

In northwestern Zimbabwe, Matopos (or Matobo) National Park is an unusual reserve between the city of Bulawayo and Hwange National Park, one that offers three special experiences: rhinos, Cecil Rhodes, and landscape.

First, at Matopos, you have the opportunity to walk close to some of the plentiful rhinos here, protected by the guides who know these animals well. It’s the determination and courage of these Park Rangers that protects the rhinos from greedy poachers. Our guide Ian Harmer, known as the Rhino Whisperer, spoke the animals’ language after having lived among them his whole life.

Among the last of the great rhinos, one of those we saw with the whisperer. The blunt horns of this male white rhino and the others we saw have grown back after park rangers removed them to protect the animal from poachers. Many well-meaning people recoil at this idea.

The story of these rhinos is neither a happy nor hopeful one yet. Because of increasing demand from Chinese and Vietnamese buyers for this supposed aphrodisiac (which only consists of the elements in fingernails), the rhino will NOT survive another decade. Demand makes the horn so valuable that poachers risk their lives to harvest the horns despite armed attacks from the rangers. And the harvesting can be brutal: ripping the horns from the live animal or crippling it in other ways. Even lethal force against the poachers is inadequate due to weakly funded protection efforts.

The parks people have long proposed to CITES (the Convention on International Trade on Endangered Species) that they benignly remove horns from rhinos and sell them legally on the open market. This should be a win-win idea: the availability of horn will meet demand and suppress prices, poachers will have much less incentive with lower prices, the animals would not be hurt, and the horns grow back. Selling a few horns on the open market could fund anti-poaching and park preservation efforts for years. But the CITES proposal meets too much ill-informed, emotionally biased resistance.

That reaction is similar to the headline horror stories of authorized trophy hunting in African countries. What we found to be most often true is that (a) the animals are older or sicker ones that are soon to die anyway; (b) the hunt is more of an organized culling than a true wild hunting safari; (c) the hunter pays an enormous sum for the experience, a boon in moneys for preservation and wildlife management work often too poorly funded by governments.

The second highlight is the grave of Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902), a still controversial historical figure. Settled by his grave site at sunset – with a breathtaking, full circle view of the Matopos hills – we reflected on Rhodes’ legacy and all the other effects of European colonial presumption in Africa.

As the dark closed in around us, our rhino whisperer, Ian Harmer, spun a long tale of Rhodes exploits, failings and respect earned from local tribes. Rhodes first became a pre-eminent mining mogul (who became rich on gold discoveries and then founded DeBeers diamond company) and eventually turned South African politician. Rhodes has been vilified for military action against local tribes as well as lauded by the native population for his fair treatment of them. Zimbabwe was named Southern Rhodesia by the South African British until the country earned its independence.

Most visitors who come here envy the incomparable location of the grave, which Rhodes himself requested. The grave itself – a large, plain metal plate with Rhodes’ name on it, sealing a tomb hewn into the rock – is less interesting than the site itself, a low bare granite hill, with naturally piled boulders atop it. Some visitors daringly climbing over the massive boulders that adorn the grave’s rocky plateau.

In addition to the intrigued crowd of people gathered at sunset around the grave, a tiny waterhole at there attracted a gecko and an elephant shrew, one of the so-called little 5 animals of southern Africa (because its nose led to its naming after the elephant).

And then there’s that 360 degree panoramic view…

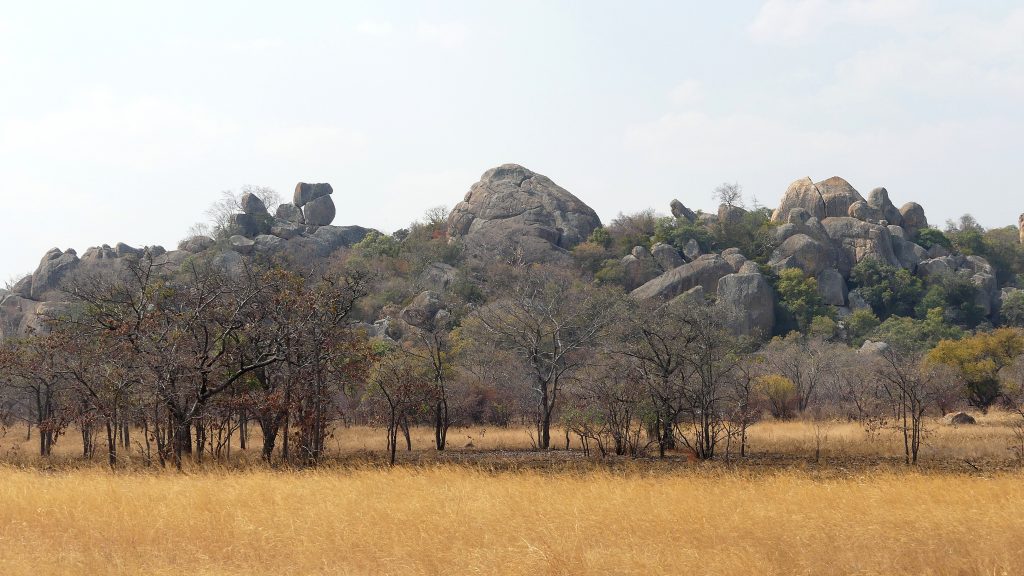

Rhodes chose this spot for his grave but, throughout Matopos, a visitor can find sweeping hills and unusual rock formations in a stunning landscape – the park’s third highlight. The hills were thrust up by volcanic action in the pre-historic past and gradually eroded into unusual formations of boulders amid grasslands.

A river in the Matopos valley, gathering spot for dozens of different animals.

Hidden within the hills and rock formations, the nomadic San people also made in imprint like Rhodes. They left a mystic record of their lives, as they roamed through this land for millenia. At least 30 thousand years ago, artists used a slightly acidic paint to burn stunning examples of native art into the rock walls. Naturalistic giraffe, oryx antelope, zebra and other animals scamper along the walls – chased by stick figure humans!

We weren’t quite sure why, but the cave also contains shadow art, as our whisperer demonstrated. This mysterious figure only shows up in the shadows, not direct light. A ritualistic entertainment, perhaps?

At this reserve, there is a lot to see or learn amid the hills, but our finest moments came from stopping atop another 100 meter high hill where our eyes and spirits contentedly absorbed this panoramic vista on Matopos.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Zimbabwe, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)