In brief: Mongolia’s people, homes and even its landscape are naturally on the move.

They say that the morin khuur, a traditional ladle-shaped Mongolian stringed instrument topped by a carved horse’s head, sounds like a wild horse neighing or wind-blown grass. That makes it a perfect symbol of the country and its restless spirit. For – like wild horses or the wind – Mongolia’s people, homes and even its landscape are naturally on the move.

That traditional home, the ger, is a rounded peaked tent of hides and cloth formed over a lattice-work structure, with decorative center posts. Gers can be disassembled and moved quickly so they have proved quite useful for a populace that has long raised sheep, goats and camels.

For – in a dry, sparse land with a long winter – their animals must follow the rains and good grasses. Even today residents of the Gobi are nomadic during the summer months, following their animals about. Often their children live at schools in town while parents wander with the herds.

For a family, one or more gers are typically surrounded by a simple low fence – which can also be moved. Inside, they park various other equipment such as the ubiquitous motorcycles to get across rugged desert routes as well as herd cattle the more modern way. Of course, Mongolian ranchers have always been expert horse riders; horseback is the traditional method of herding, with a long pole to direct the animals.

Outside the fencing of a family’s gers, the animals remain when they are not roaming about, along wtih the simple outhouse toilet. Iron stoves in the center of the ger – powered by wood or, better yet, dried camel dung – serve for heating and cooking. Gers are so central to the culture that even city dwellers use them as semi-permanent homes within their roughly fenced land.

While exploring the Gobi desert and beyond by car, we slept in half a dozen gers sleeping – just like the family – on wood frame beds with straw mattresses (which we covered with a sleeping bag), rough pillows and weighty animal hair blankets. The guest homes differed a bit from the family’s ger, with individual, not shared, beds, no cooking tools or storage, and sometimes greater space to accommodate more people.

Nor did we have to share a ger with a baby yak, as one family did, because its mother could not provide enough milk. During the night the little yak kept rustling, bleating, peeing and more. A hard day’s night – and stinking one – according to our guide, who had to sleep with them.

Far different are the gers in guest camps, which consist of dozens of sizable gers, outfitted with plusher mattresses and storage chests, and typically adjacent to a central building with dining and toilet facilities and hot showers. In the off-season, these camp gers often wander away leaving just circular concrete foundations behind.

We appreciated the amenities occasionally, but felt more at home in a family’s guest ger than the overcrowded camps.

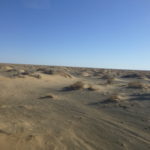

Everything in the Gobi and the harder-surfaced, stony middle Gobi, the two of which are divided by a mountain range, is restless including the surface itself. The Khongor sand dunes continually shift in size and length, up to 300 meters high at times and 100 to 200 kilometers long. They are only stopped as they sweep up against a long Gobi mountain range. The rest of the desert continues to move as well. In an extensive project across several areas, the national government has planted native scrub trees in sizable plots in order to keep Gobi sands from drifting over viable grassland areas.

In the winter, wind-blown snowstorms add a white layer to the surface. One day, while we were nestling around the iron stove at a family’s guest ger, a snowstorm scattered its double-humped camels and goats. All the adults disappeared for hours in order to track them down and secure them from the storm.

When we awoke, four large snow-dusted males – with Rastafarian clumps of fur around head and draping down from their necks – sheltered against the ger fence where the family had tied them safely.

Over the restless surface of the desert, or just beneath it, bustles the animal life of the Gobi, however still the sands may seem. We passed many free-ranging herds of camels plodding along, watchful over their biennial babies. The endemic Mongolian gazelles, the color of the sands, raced away from us. Huge herds of sheep and goats, many black-faced, grazed on the nearly invisible grasses of the springtime. Hawks and eagles prowled near, and vultures disposed of carrion.

Tiny pale critters – mice, lizards, gerbils, rabbits – whose near invisibility is their best defense, skittered along the surface avoiding those flying predators or us. But millions of years ago, we would have seen giants instead. Dinosaurs reigned here, leaving many traces of their nests and eggs behind.

Not strictly of the Gobi, the endemic Mongolian wild horses (which we have noted in another post) are among the most famous drifters in Mongolia, with their distinctive black markings on orange-gold hides. We could not hear the sound of the Morin Khuur violin when we saw them foraging. No wind sawed through tall grasses. Nor did the wild horses neigh much. Instead they glowed in the afternoon light.

As did the shifting colors of the desert when we rode through it. Govi/gobi is Mongolian for the color orange, certainly one of the more evident hues on the sand. Yet, to us, the colors shifted beautifully with the changing sunlight. One day, a steely sun filtered through the clouds. Look toward it – the meager grasses and shrubs show dark green against a grey-brown or purple surface. Now look away from the light: the plants transform into pale green and light brown against a golden or red-auburn ground.

Hardened, weathered hills of sand thrust up from the otherwise unremitting flatland. Look toward the sun: far off, they show dark blue in the haze, and dark brown when closer. Look away: the far hills turn evanescent blue, or reddish-brown closer. You had to be there, in the moment.

In this way, driving along the deserts of Mongolia (or riding on horseback in the season) lets you join in all the restless movement of the Gobi. What roads there are – from those nearly undetectable by us to those marked every few kilometers by a small, set stone or by a roughly heaped cairn – make you part of all this movement. Even an experienced driver needed to seek directions from the local ger residents or retrace his steps. Our wandering passage connected us with the restless desert of today and with those here who moved with the grasses before.

(Also, for more pictures from Mongolia, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)