Though preceded by others for millennia in mastering the challenges of Greenland, the Inuit and Norse arrived a thousand years ago with very different aims.

The Norsemen (Vikings)

As the Sagas tell us, in 982 AD, Erik the Red and other Norsemen sailed west to a rumored land he later named Greenland, founding a farming community he called Brattahild (now Qassiarsuq). He had stormed out of both Norway and Iceland in criminal exile. Later his son Leif went back to the home countries, but returned to Greenland to convert the Norsemen to Christians. Then Leif sailed on to discover “Vinland,” or eastern Canada.

Meanwhile, a bit south on the fjords, Erik’s good friend Einar developed his Greenland community Gardar (now Igaliku), which thrived on harvesting the sea, as well as sheep and goats. Soon Gardar was large enough to become a church bishopric for a few centuries. There we explored it’s much more substantial remains and learned how centuries of ancient skeletons were buried.

By the 1400s, though, the Norsemen mysteriously disappeared from Greenland until their Lutheran descendants returned in the 18th century.

We did two delightful hikes through what remains of their ancient world in the World Heritage sites at Qassiarsuq and Igaliku.

Qassiarsuq (Brattahild)

The site of Erik the Red’s Greenland community at Qassiarsuq, looking toward the current harbor.

The arrival of Leif Erikson and Christianity in 1000 AD at Qassiarsuq was honored in 2000 AD with this replica of the tiny church of Tjodhilde, Erik’s wife and Leif’s mother, the first convert to Christianity.

One other interesting replica in Erik the Red’s farm village is this Viking longhouse. On the outside, its turf walls form an elongated dome with one doorway on the side and a roof vent on top for smoke. Inside, we saw how the families of Erik’s community lived – well, communally.

At the high point of our hike from Erik the Red’s Qassiarsuq, we picnicked atop a knoll with a vista down to the adjacent fjord, filled with gleaming icebergs.

Even the horses here adorn the landscape, like this friendly one who nibbled at our hands.

Along our Qassiarsuq hike, within the extent of Erik’s farmland, we had noticed these purplish grasses making a strong contrast with the more prevalent green shoots. Here we were astonished how they seemed to flow down from the hilltop like a glacier.

Erik’s farm was nourished by plentiful springs and streams like this one completing its descent to the fjord. We were told that 20th century farmers, investigating options to control water flow, found that the old Norse settlers had already discovered the best places to add dams and diversions.

Igaliku (Gardar)

From a trail, we descend into Igaliku, Einar’s Gardar, where he would have arrived by boat. Minus a few wooden houses in the style of the much later Norwegian settlers, this perspective from the hills above the town should have been much the same a thousand years ago.

The landscape near Igaliku

The Norse ruins are quite substantial in Igaliku. But, even up to the middle of the 20th century, families removed stones from the ancient buildings to make their new ones. This one shows off its attractive array of old Norse stones as well as, on its partially exposed end, the thickness of its walls.

In Igaliku, remnants of the meter-thick lower walls of the bishop’s church showed its substantial size. But most impressive were the original doorways of this building and its thick walls (most noticeable at the upper left of the structure). Here the church collected tax in the form of labor or food and farm goods, which were also stored here. It was expensive to have a bishop in town. While most people lived communally in longhouses or in small huts, the bishop’s house was large enough to have thirteen rooms.

Around 1100 AD, Einar’s Norse farmers created this water collection system at an underground spring in Gardar. It’s still in use today for water pumped to houses by equipment in the blue building and as a watering hole for cattle. Before electricity arrived in the 1980s, its frigid cavern served to store perishables in the summer just as it would have in Einar’s time.

Later, after our engaging dialogue of Baaa’s with these sheep, we learned that the market for local wool has collapsed. The sheep still yield useful milk, but the wool they grow is just burned now. Remarkably, the sheep in Igaliku claim to be descendants of the sheep that came here in the 18th century with the Norwegian man who re-established the town.

The Inuit

Four thousand years before the Norse arrived, people from the very north of the land that became the Americas mastered the most challenging living conditions on earth.

First, the Saqqaq and then the Dorset people followed the ice bridge from the Arctic north of Canada eastward to Greenland. Far north of the later Norse settlement, they settled a region rich in sea animals and surprisingly agreeable in the summer.

Only the artifacts discovered under the turf at places like Sermermiut, where the tundra slopes to the fjord at the Ilulissat glacier above the Arctic Circle in western Greenland, remain to tell us about them.

About when the Norse arrived, the Thule people, or the Inuit, rowed their boats from northern Alaska, following the whales, seals, and other food sources teeming in these waters. To catch them they used harpoons that were surprisingly small, but effective. The Inuits’ superior hunting skills and boat technology let them thrive, while their animist beliefs made them respect the bounty around them.

Below was the location of the Sermermiut village at the edge of the icefield along the moraine of the Ilulissat Icefjord. Here archeologists uncovered thousands of years of tribal artifacts for the three different cultures who lived there. Only in the last few years did the last villagers leave due to government inducements and climate changes (the cause of rising seas and dangerous calving icebergs).

The Inuit finally had to adapt to the incursion of Norwegian and Danish colonizers, eager for those same valuable marine resources and the chance to convert souls to Christianity. But the Inuit elders still tell the tales of their hardy ancestors.

Until the colonists established permanent villages that altered Inuit lifestyles, the Inuit were nomadic, moving their camps as the animals they hunted shifted around feeding regions. These lean-tos of animal skins were easy to pack and move. They only required digging a shallow pit about the size of the tent for more comfort and head-room. Other practices like tattooing also changed with the new religion.

To the Inuit, all things, animate and inanimate, possessed a spirit. And perhaps the greatest of these was the spirit of the waters, called the Mother of the Sea. This monument at Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, honors her.

In this statue, she is surrounded by the animals that she offered in plenty to sustain the Inuit – seal, fish, polar bear, and walrus (as well as the uncredited whale) – while nurturing a young Inuit. In her honor, the Inuit would waste nothing of the animals whose lives they took for sustenance: the skins for clothing and boat sheathing, the meat for food, the bones for tools, even the blood for waterproofing the skins. What they could not use went back to the Mother.

Boats of the Inuit on display at the National Museum in Nuuk. The large boat was the women’s boat. When a group moved its location to follow the sea animals, four or more women would paddle this large boat filled with household items and tents. The men paddled the slender kayaks. The boats were well suited to the tough environment, and the Inuit’s various harpoons and cutting tools were specialized for each type of prey.

Not only would the tribes move from place to place by boat, but they also moved across ice and snow with dog sleds, using sturdy dogs like these in large groups to pull the loads. At Ilulissat, near the Icefjord, such dogs are still bred for sledding work, though many of their loads are now tourists instead. When the hundreds of the dogs here started howling, they sounded, even from afar, like a lot of wolves on the prowl.

Burial practices were simple, the internment of the bodies in a pit covered over and marked by stone cairns like this site at the fjord near Narsaq. The dead were expected to complete their journeys in the afterlife so a site near water was especially fitting.

These mummified bodies were buried in the late 15th century and preserved in the tundra till discovered in the 20th century. They were buried with extra furs, decorative items, and tools to aid their journey into the afterlife. Their everyday outfit of jacket, pants, and boots even until the 20th century was typically made of reindeer or sealskin, but lined with downy bird feathers directed inward for warmth.

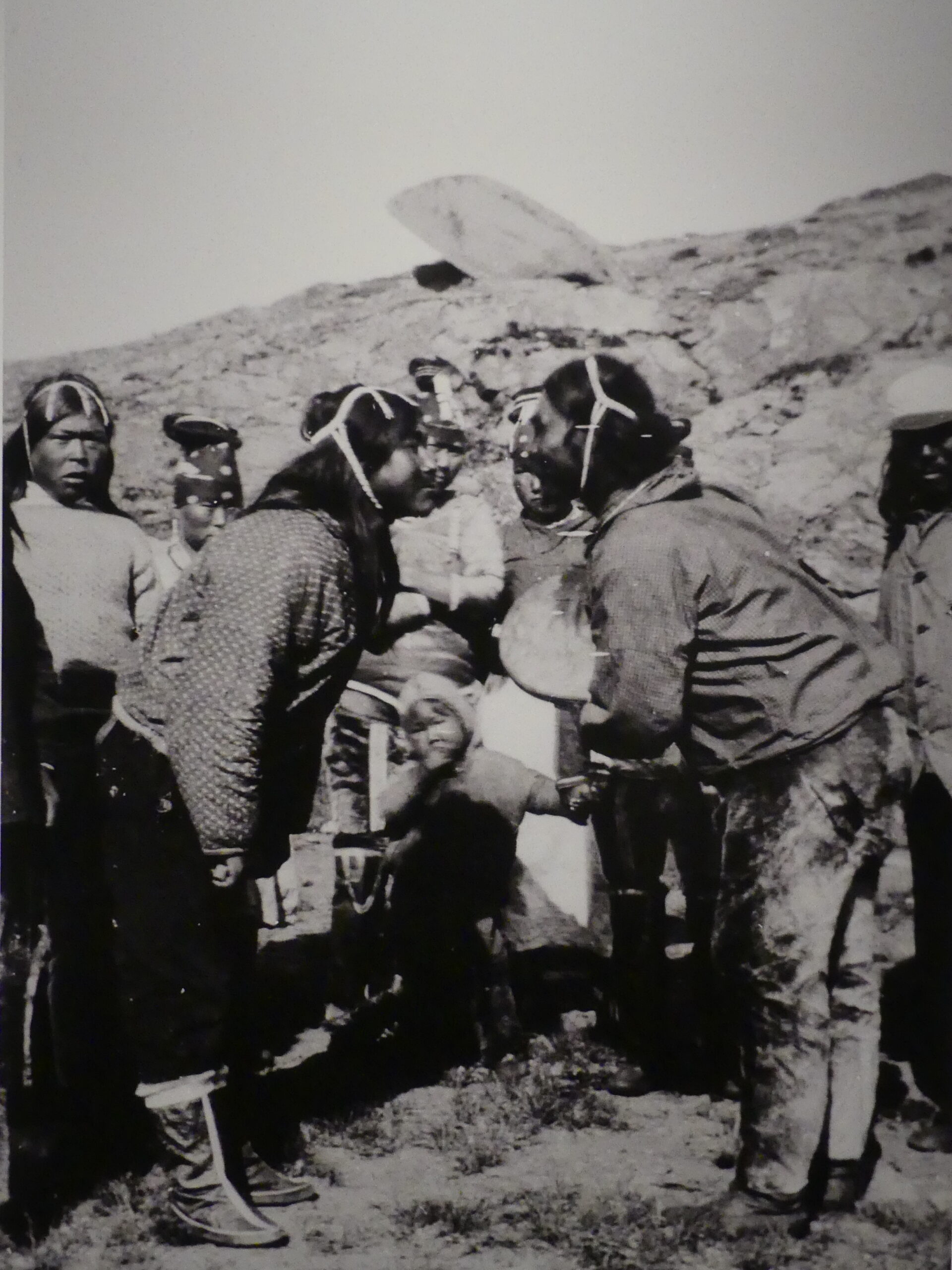

In this photo from the National Museum, you can see the clothing in use. The men are engaged in a drum song battle with unique throat singing, a ritualized warlike contest that tests who can outdo the other like a poetry slam.

An example of the more ceremonial costume of the Inuit with photos of some owners. The skins, the beadwork learned from the colonists, and the textiles are so labor-intensive that these costumes cost thousands of dollars. The colors indicate your status in the community: unmarried, mother, etc.

Today, western clothing dominates daily life. This group of men awaits friends and families preparing to disembark from the Sarfaq ferry that takes people from village to village along western Greenland.

Norwegians of the 18th century

The Lutheran ministers who came to Greenland from Norway in the 18th century aimed to convert the Inuit to Christianity, while serving the growing population of Norwegian emigrants. In a land with no trees, they used wood from the home country to build Norwegian-style churches like this one at Sisimiut…

The other settlers saw opportunity in trading walrus tusks, a plentiful source of ivory, or whale oil – as well as raising sheep. And they built large and small peaked-roof houses like these.

Another family group waits to embark on the ferry, a more European mode of travel.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Greenland, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)