In brief: We share our not so secret pleasure at revisiting treasures at three of our favorite museums in Lisbon. For a touch of paradise, they are hard to beat.

A secret pleasure known to residents of a town, or to those who return often, is the revisit, a look at the treasures within a museum collection for the second (or third, or fourth, or…) time. You seek out your favorites, uncover masterpieces you missed before, or just revivify your original experience. While the pandemic held us in place in Lisbon, we went back to three of our favorite museum pleasures here: the charms of the Medeiros e Almeida collection, the baroque fancy of São Vicente de Fora church, and the impressive range of the Gulbenkian. For a paradisiacal experience, these are hard to beat.

Medeiros e Almeida Mansion

Of all the small museums in Lisbon, this is our favorite, the dazzling collection of period furniture, decorative art and fine art by Antonio and Margarida Medeiros e Almeida. We returned to it with equal delight after a few year gap. There we toured again the mansion’s dozens of rooms, each beautifully arrayed with the objects they loved.

Medeiros e Almeida made the money for this as a 20th century industrialist, selling British Morris cars in Portugal, extracting sugar from the Azores, and finally running the predecessor to TAP airlines.

The couple expanded their home, an 1896 Beaux Arts building acquired in 1943, to accommodate all they collected. Before they died, he and his wife moved nearby so the collection could become a museum.

His passion in collecting looked mostly back to older times, all the way to the 2nd century BC. Here are just a few of the wonderful items and spaces in the museum.

Just one example of the rooms to visit in the museum, with fine art on the walls, clocks, furnishings, delightful tapestries, and more. One highlight of this room is the elaborate fireplace setting, inset with paintings and impressively topped by an effusion of glass panels and figurines.

Each room in the mansion features beautifully painted ceilings like this wood paneled surface of 18th century pastoral moments.

One of the grandest displays in the museum is this room dedicated to a collection of 18th century Portuguese tile work on the subject of the seasons and four continents, plus an equally splendid painted wood ceiling depicting the continents. In the midst of it all blooms an elaborate pink marble fountain. We had a bit of trouble deciphering the iconography of the images, as most of the scenes featured couples in some sort of love play.

A striking 19th century marble of Veritas, the Roman goddess of truth, by Raffaelle Monti – located with the azulejos room (just visible within on the left). She does her work by unveiling, while crushing the mask of falsehood and a serpent of evil. But the glory of this statue is the sumptuous illusion of transparency and lightness in the veil itself.

Some of the huge display of handheld fans collected by the couple, dating back to the 18th century. We recalled this exhibit vividly even four years later. The ones here are some of the oldest, but the collection includes so many others that rival the handiwork and colors, or go another direction with gossamer lace. A woman’s handling of her fan could demonstrate a wide variety of romance memes, from seductive to dismissive.

One whole room is devoted to the timepiece collection. Numerous glass cases in this room display hundreds of pocket watches. Medeiros e Almeida is quoted as saying that time obsessed him because it’s passage was the only thing he could not control. And throughout the house old clocks grace individual rooms. Most of the clocks still function.

These here are among the oldest from the 18th and 19th century, some of which were carried onto battlefields of the Napoleonic wars in Portugal.

One of the most unusual timepieces in the collection is this 17th century hourglass tower decorated in amber from Gdansk, Poland. The three sand-filled hourglasses in the middle mark the quarter hours.

The partly reflected backside of the clock shows the months. At the top appear to be some chess pieces. In the base are compartments for writing materials.

Medeiros e Almeida probably loved the motto just above the dial: Semper prima; semper ultima. Time is always first and last.

Early Chinese ceramics dating back to 200BC. Below on the right are various funerary pieces, and above some drinking gnomes. A later Tang dynasty delight is the prancing polo player at the top middle, both realistic and spiritual in its ascent.

An exuberant “fish bowl” vase from the early Ming dynasty in the 16th century.

The fully set dining room, using just a bit of the plentiful tableware on display elsewhere.

The room description highlights a dinner in 1954 with Princess Grace (Kelly) of Monaco and Prince Rainier, though surely other renowned people dined with the couple. Royalty sat at the opposite ends of the table, with Antonio beside Grace, and Margarida beside Rainier. No less a performer than the renowned singer of Portuguese fado, Amalia Rodrigues, serenaded the group.

A room used often by the family for lounging, games and music. An early pianoforte occupies one honored space. Several paintings from the Brueghel family are here, and in the adjacent hallway a fine collection of nature scenes by the 17th century Dutch painter van Goyen.

Across the hallway is the dining room, so one presumes the Monacan royals relaxed here after their dinner. We had to sit elsewhere.

São Vicente da Fora Church and Monastery

The 17th/18th century church and monastery of São Vicente da Fora perch atop one of the city’s hills (“da fora,” or beyond the old city’s walls).

This panorama taken at Portas do Sol shows the distinctive twin towers of São Vicente church on the opposite hill, along with its monastic walls – as well as demonstrating why Portas is one of the best places in town to take some refreshment while enjoying the view.

Perched atop one of Lisbon’s hills, the rooftop of São Vicente provides some superb vistas of its own over the Tejo and downtown.

Here along the rooftops we show how much we enjoy visiting the church and monastery.

The church was originally begun after the defeat of the Moors in 1147. Then the king effectively made Vicente a patron saint of the city by bringing his remains here by boat, transport commemorated as the city’s emblem. The church itself today invites a long visit to savor the marbled rooms or the countless scenes in blue and white tile

In the morning, the late Renaissance interior of the church – with a barrel roof and central dome – blazes with light from behind the baroque altar.

The rightly famous sacristy consists of a dizzying display of inlaid polychrome tile.

This receiving room in the monastery presents a visual splendor through the multicolored marble on the floor and the banister, the panels in blue and white tile telling the story of the siege of Lisbon by Afonso Henriques in 1147, as well as the elaborately painted trompe-l’oeil ceiling.

Country landscape and mythic figures mingle even at sharp angles on the staircases, entertaining all who climb or descend them – carefully. This “runner” features especially fine floral detail and animal figures.

The halls of the monastery are swathed in tile scenes of pastoral life and landscapes from the 18th century.

Dozens of special scenes in tiles were also created for the walls of the monastery. Each depicted a fable written by La Fontaine, the Aesop of mid-18th century France. Unlike the learned of that time for whom one panel would evoke a whole fable, today few of us know these stories. Fortunately, there are helpful plot notes for each.

This one, with the picturesque waterfall, is the Cat and the Mouse. As the panel shows, the cat was caught in a net and pleaded with the mouse to gnaw the ropes and free him. In exchange, the cat would protect the mouse from the neighboring owl and weasel (who can be seen on the same tree). The mouse freed the cat, but demurred from its invitation to come close to be thanked. The mouse stayed at a distance, wisely remembering the instincts of the cat.

The Gulbenkian Museum: The Early Years

The Gulbenkian Museum includes art works that span over 7000 years, from the dynasties of Egypt to the 20th century. This visit, we decided to slow down and savor the earlier periods, rich with Egyptian, Asian and Middle Eastern art. We set the next visit to discover the treasures of the European art collection.

Alabaster bowl from ancient Egypt, about 4700 years old

Richly engraved stele from ancient Egypt, about 3500 years old

A life-sized figure strides across this Assyrian bas-relief, carved in alabaster nearly 3000 years ago

For 2500 years, all 16 legs of the hard-working Apollonian horses have churned across the face of this Alexandrian era coin, about the size of a euro yet with fantastic detail.

Marble bust of a satyr’s head from 2nd century AD Rome

A Seljuk bowl from Iran dating back to about 1200 AD, with an enthroned ruler encircled by sphinxes

Huge 14th century glass bottle from Egypt or Syria

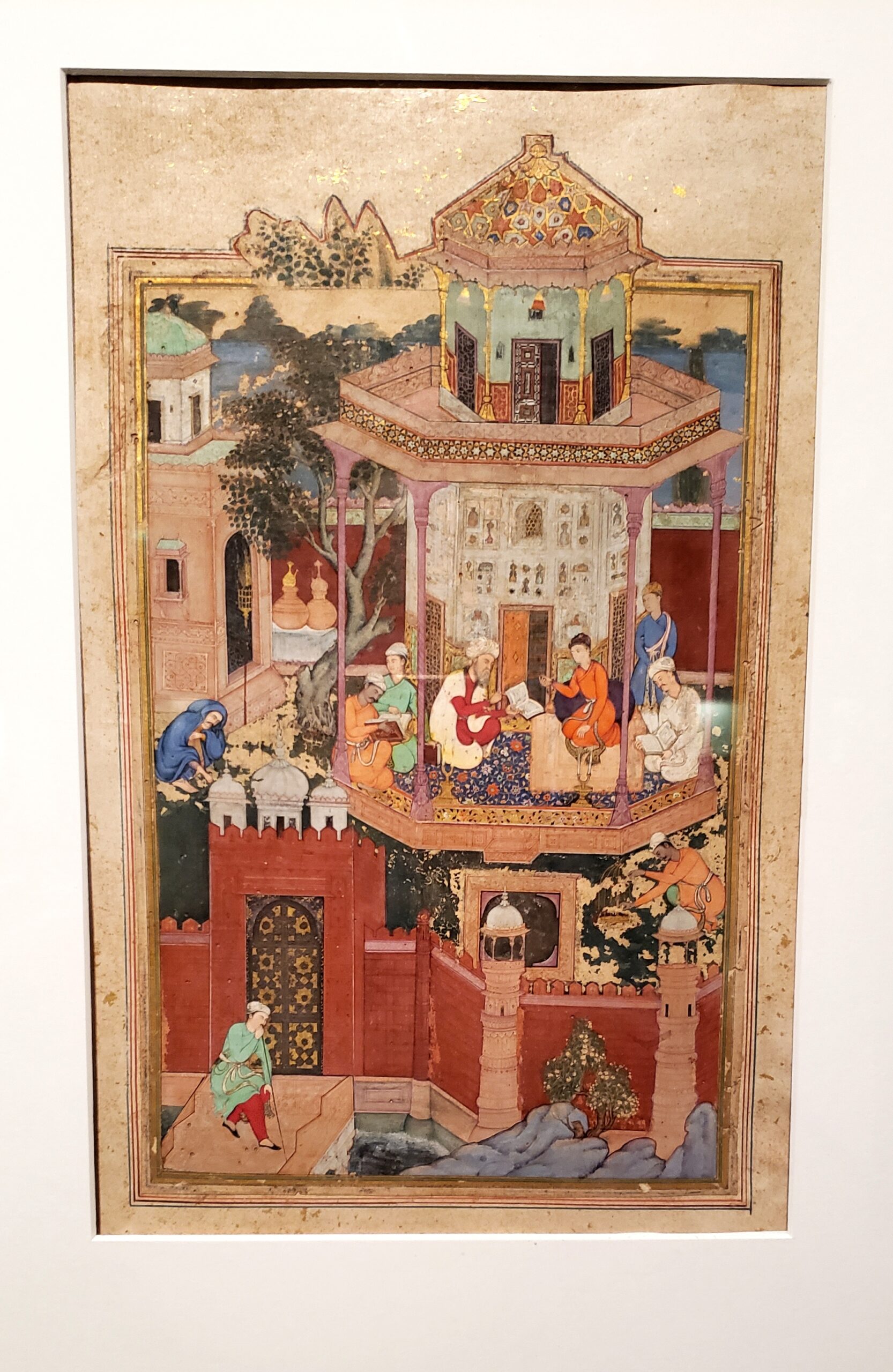

A watercolor of courtly scenes from Mughal India, dating from the 16th or 17th century

A gaggle of Qing dynasty pottery

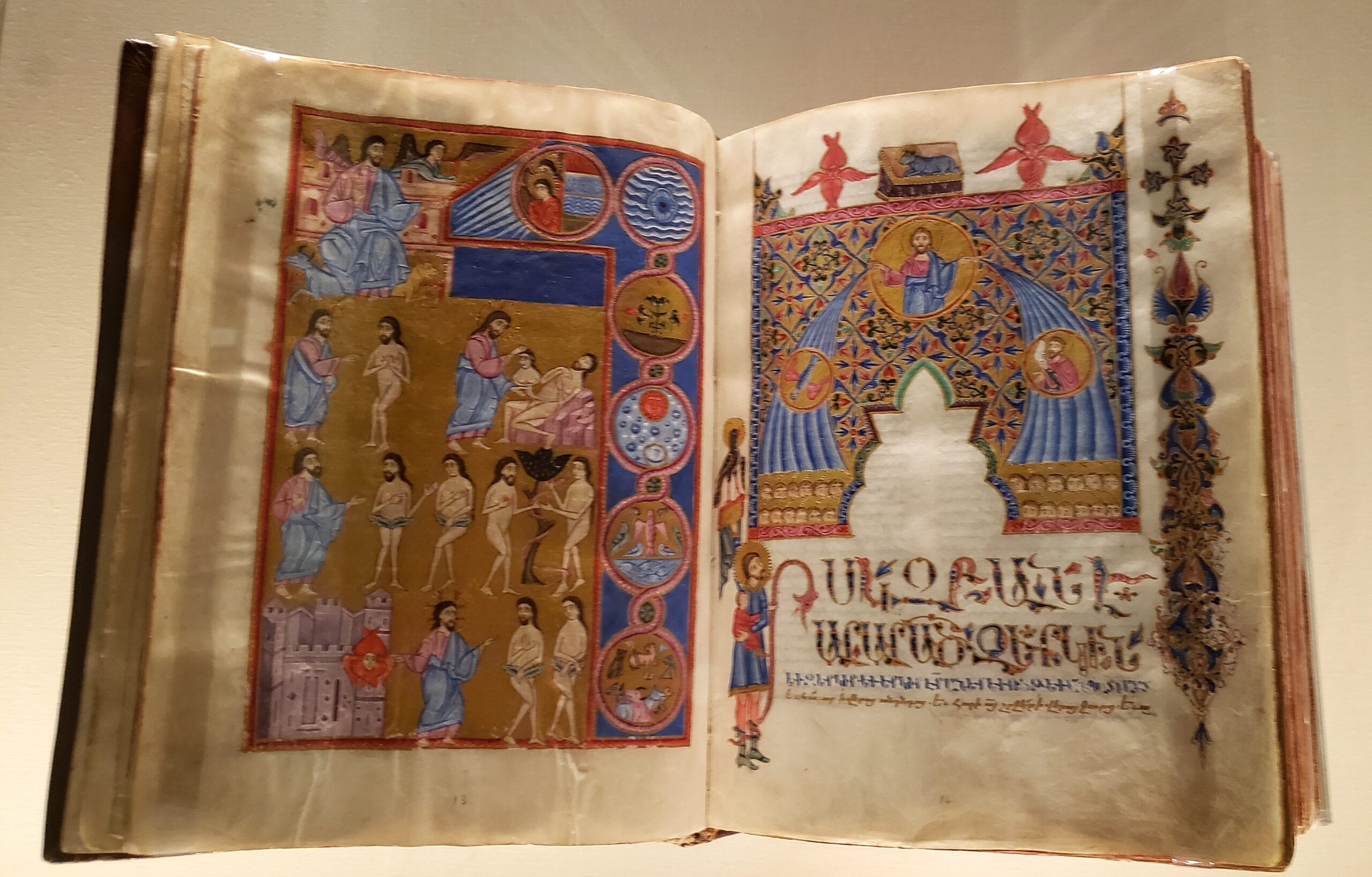

17th century illuminated Bible presenting the story of Adam and Eve, Paradise lost from Istanbul

Time to party, as the band just keeps on playing. Detail of late 17th century Chinese standing screen, called the Coromandel.

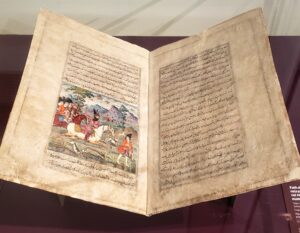

“The power of the word” – part of an exhibit of how ideas and stories are transmitted. This is a mid-19th century copy of “Kalil and Dumna,” in which two jackals help educate princely leaders on how to do their jobs.

Based on a 3rd century Indian text in Sanskrit, the book was translated into older Persian a few hundred years later, into Arabic after a few hundred more years, and then into modern Persian by the 15th century.

Gulbenkian Museum: Finishing the tour

Our second visit to the Gulbenkian Museum on a free Sunday afternoon picked up where we finished before, at the admirable European collection of art, books, sculpture, and furnishings gathered by the founder. We enjoyed old favorites and were newly attracted by other masterworks spanning six centuries.

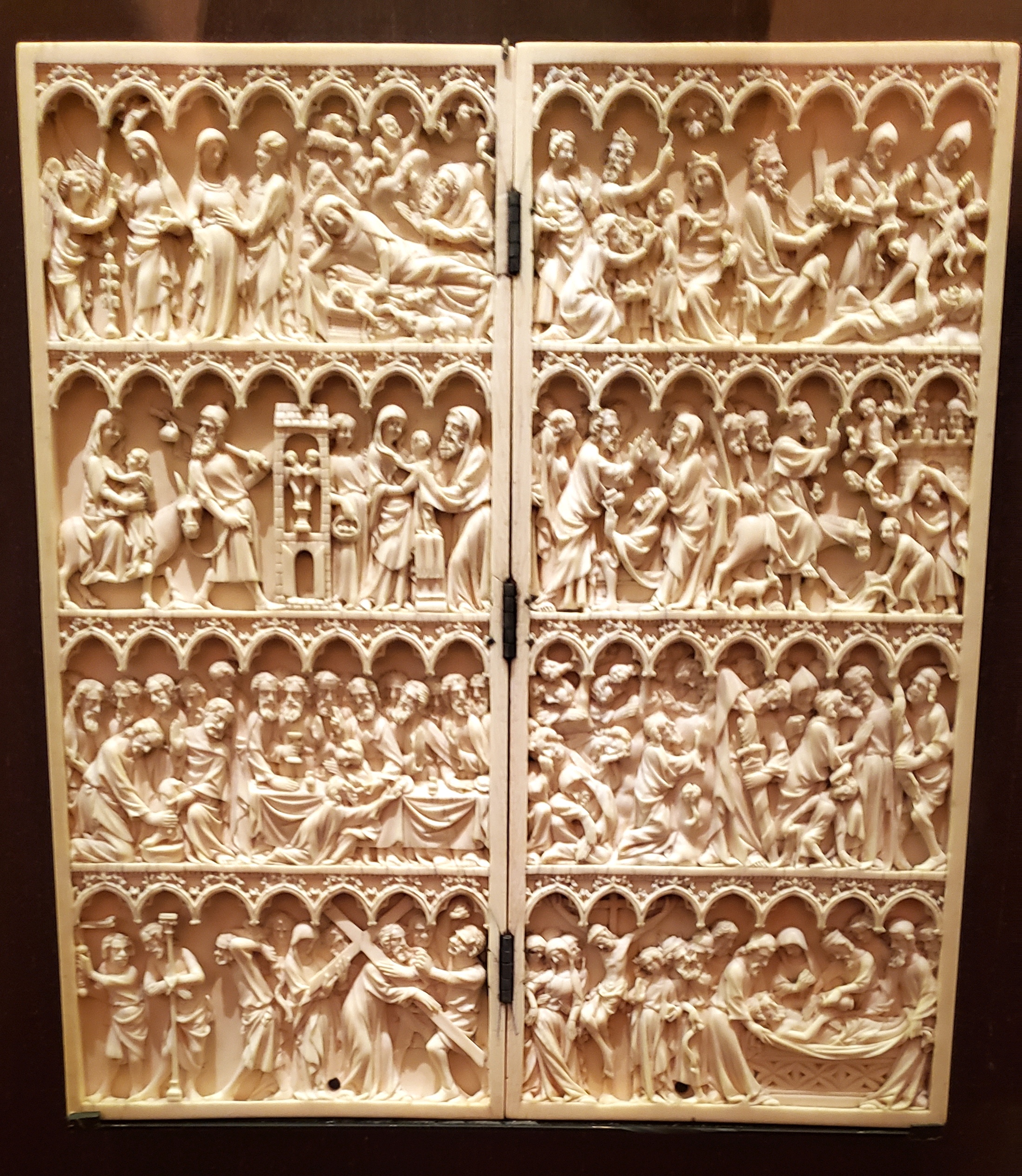

Mid-14th century ivory diptych with biblical scenes, a miniature treasure of elaborate individual detail and group dynamics. Other earlier miniatures dated from the 13th century, but we couldn’t take our eyes off this one.

Late 15th century Portrait of a Young Woman by Ghirlandaio, one of the most striking of the many Renaissance works in the collection.

Not a self-portrait, but a deeply moving Rembrandt Portrait of an Old Man, capturing the very nature of time, in the gains it gives in wisdom and the losses it imposes on the body. We loved the two Rubens paintings in the collection, but our photos didn’t do them any justice.

Probably the best setting for a piece at the Gulbenkian is this 18th century marble statue of Diana the Huntress, who seemed prepared to leap into the wooded grounds of the museum, chased by her shadow.

Mid-18th century silver centerpiece by Durand is one of many in display cases, within a huge collection of period furnishings.

A whole room is devoted to 18th century Venetian landscapes by Francesco Guardi, to us the premier portrayer of that city in his broad panoramas and meticulous detail. You could spend several enjoyable hours in this room alone.

We have seen many marbles by the Romantic era sculptor Canova, each of which is both stunningly alive and otherworldly as well. No less eerie and arresting is this bust of a Roman Vestal attendant.

JMW Turner’s Wreck of a Transport Ship first grabs attention with the turbulence and danger of the sea, but those who risk approaching the violence can see the care with which he captures the human emotions of key figures on the ships.

You can count on Renoir to brighten the mood, as in his portrait of Mme. Monet (whose husband has several works on display here) in a pose reminiscent of the earlier Manet and the later Matisse. She is lying down, but is rendered as vividly active.

Edgar Degas himself showed up in the galleries while we were there, with a piercing gaze, a flippant salute, and a stormy mood outside (and inside?). A second Degas portrait of an artist was even more bizarre.

A casting of one of the defiant burghers of Calais by Rodin draws much attention from the colorful Impressionist paintings around it.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Portugal, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)