In brief: In the midst of salt flats and arid desert, palmy oases around Tozeur have long sustained intriguing towns.

You travel for hours through Saharan desert or drive very straight along an endless causeway through expansive salt flats (chott), such as this small section around Tozeur, with distant mountains behind. The government built the long causeway through it to enable commercial salt production. Oasis water runs through it in channels.

In the distance, a clump of green appears, eventually becoming a forest of palm trees erupting from a fertile desert oasis, 1000 hectares (2500 acres) in size.

Here is just a small section of the expansive Tozeur oasis, as seen from one of the many dirt roads criss-crossing it. The French occupiers, we were told, turned this oasis and others in the area into gardens, filling them with palm trees and fruit trees that still occupy the space. The yearly yield from the oasis is about 30,000 tons of dates. Some 200 springs and wells supply the water. Similar oases nurtured other towns like Nafteh and kept nearby canyons fertile enough for farming.

Since the middle ages, the bounteous oasis and the brick-making clay of the Tozeur area nurtured a growing population as well as trees. Walking about its old district of narrow lanes, you find poetry in brick – intricate designs that grace the houses, the mysterious L-shaped passageways and mosques. Behind many of weathered wooden doors hide grand villas in the Ottoman style, whose large central courtyards feature lush gardens nurtured by that still abundant oasis.

Let’s start with probably the finest of the brickwork passageways connecting the old quarter’s narrow lanes, with a myriad of geometric designs (chevrons, ovals, abstract features), as well as arches, stone columns, and a modern electrical touch. This quarter, Aouled el Hadef, arose in the 17th century after Ottoman destruction of the medieval city center introduced great wealth and distinctive style to an outlying district. This became the commercial center, the equivalent of the medinas of northern Tunisia towns.

One of the most attractive of the old, grainy wood doors in the Ottoman quarter, demonstrating a number of special features. The three separate knockers were intended for different users: one for a man, one for a woman, and the lower one for a child. Often that third one appears on a separate small door set into the larger door.

The rivets in the door are common in all the old centers of Tunisian towns. Here they are arranged in geometric and floral patterns. Often they form symbols – such as Solomon’s seal, paired fish, or an inverted hand – that invoke good luck or ward off the evil eye,

Open air markets are busy every day, but during Ramadan the activity seems particularly intense, as fasting shoppers stock up for the large meals of iftar.

The open air market sprawls along the streets emanating from the permanent food market, a newer building with decorative brickwork similar to that of the old quarter.

That guy on the scooter is just one of many jostling for space with the pedestrians, a common occurrence in Tunisian towns.

Welcome to centuries past! This is a typical arched passageway connecting narrow lanes and hiding entrances to villas. The wood ceiling is original and the large weathered door ahead is common in the old town. Other archways form surprising intersections of lanes that you cannot detect until you’re within the archway. Unsurprisingly, this all might look like a movie set: many scenes from The English Patient were filmed here and in the nearby deserts.

One of the old portals to the Ottoman era quarter in Tozeur demonstrates several of the brickwork effects that grace the city’s buildings, with chevrons running horizontally, geometric shapes formed between them, and arches as fake-windows and actual passageways. The lamp might look similar to those lit in the past, but clearly has been modernized with electric wiring.

The architecture of the nearby city of Nafteh, another town emerging from a large oasis, used brickwork designs like those in Tozeur. Sadly much of that ancient beauty was ruined in a huge flood, though some has been revived or re-created.

This elegant mosque tower shows plenty of arched windows and a host of cheering anthropomorphic figures dancing up and down its face.

Along one of Tozeur’s main streets near the large market center, this plaza featured a brilliantly lit canopy at night.

The last nighttime prayers resound across old and new Tozeur from this charmingly lit mosque watchtower.

In addition to its lyrical brickwork, Tozeur honors one of Tunisia’s most renowned 20th century poets, its native son, with the central street of the town and an elegant tomb.

Here is a section of the large tomb – built in brick, of course – that houses the crypt. Aboul kacem Chebbi died at 25, but his verses on themes of liberty (notably his defiant poem, “To the tyrants”) rallied people during Tunisia’s Arab Spring. And he wrote part of the country’s national anthem. This corner shows an example of the tiled artwork inset all around the tomb. The central banner of each one cites some of his verse, in Arabic or in French.

Earlier in our drive to Tozeur, some of the desert still allowed for agriculture. Here’s a furrowed section of what otherwise seemed desert land, planted with olive trees. We guessed the furrows helped moisture retention. As we went deeper into the desert, and conditions became drier, we found the olives trees planted farther and farther apart.

Desert canyons: Chebikah

At the western edge of Tunisia, near the border with Algeria, sinuous desert canyons and sandy flatlands alternate with green palmy oases. This entire area offers striking vistas and colorful sights, especially Chebikah canyon and oasis, an hour’s drive north of the old town of Tozeur.

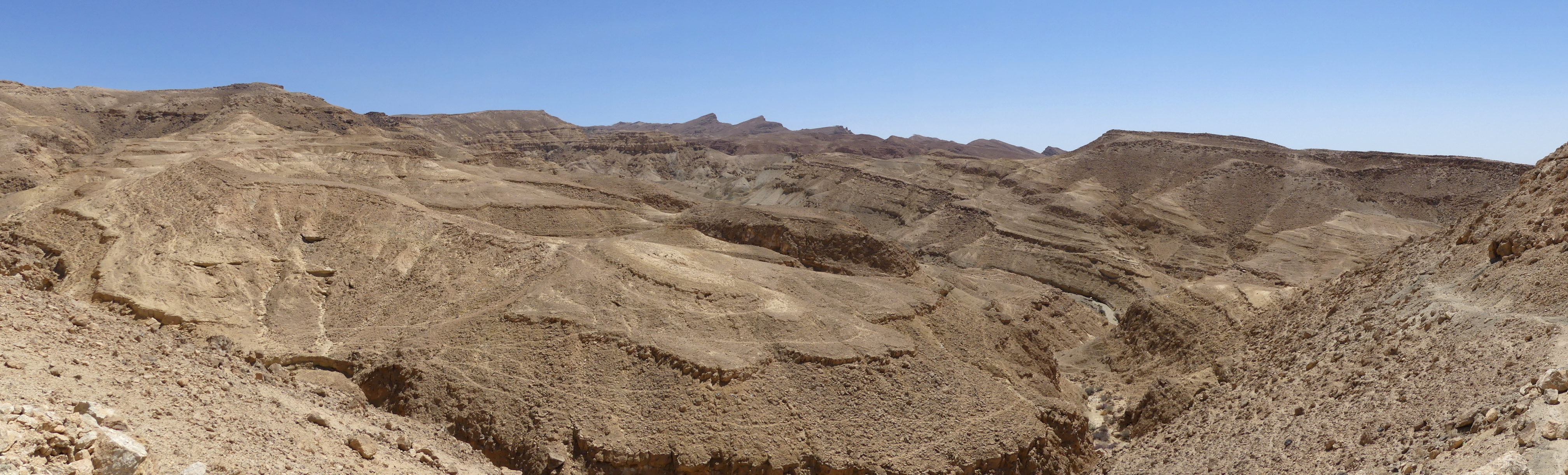

We hiked around Chebikah, marveling at the rocky seams resulting from violent upheavals in the past, with especially dramatic views where erosion has exposed those seams.

Old layers of earth ripple and flow among the sandstone surfaces of the mountain at Chebikah

The limits of Chebikah canyon, where the rocky upheaval of the mountain tumbles down to the palmy oasis and ends at the flatlands of the desert, which continue onto the salt flats along the horizon.

Though we are deep in the desert, the springs of this oasis keep water flowing year-round.

A resident in the pool near the source of the springs

Water flows out of the springs at Chebikah canyon

Nearby was the town of Mides, whose limit is the old Berber fortress at the upper left. The village has perched atop this colorful winding canyon for centuries.

The waterfall called the Grande Cascade is not at all grand these days although these very colorful cliffs around it still make a visit worthwhile. The water flow has been diverted for agriculture, and even Tamerza, the town upstream of the cascade, has effectively dried up, with hotels and restaurants falling into ruin, languishing for visitors around what used to be a river.

Just one example of the swirling patterns of the sandstone cliffs and canyons in this northern desert.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Tunisia, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)