Algeria is a large country which seems at first divided into two zones, a coastal landscape and vast desert. We found that Algeria offered much more diverse ecologies and terrain than this simple division. In this post, we share our pleasure in that diversity with three very different natural landscapes – limestone hills in the northwest, high plains and thermal waters at the Aures Mountains, and the canyonland of the Rhouffi Valley.

For more on coastal Algeria, click here. For more on desert and oases, see our articles about Timimoun and Ghardaia.

Limestone hills and caves of Tlemcen

We discovered a natural treasure in the forests of Tlemcen National Park near the city that was once a stronghold of Muslim empires before the Ottomans and an important religious center.

Here, amid a striking landscape of limestone hills and sandstone canyons, numerous caves wind deep underground. We were told that Beni Add Ain-Fezza, the one we visited, is the second longest in the world, meandering all the way to Morocco about 60 kilometers away.

Other stories talk about smuggling goods across the borders, or refuges for freedom fighters against the French. We could not confirm any of these tales, but someone did decide to permanently block passages deep within.

Fortunately, visitors can still access the colorful caverns closer to the entrance.

Below are some views of the limestone landscape near the caves.

The lighting in the cave was well done, but these (and the other interior above) show the actual colors in the cave formations as revealed by the lights.

Organ pipes? Melted candles? These formations are often seen in limestone caves, but always dazzle us.

One of the most unusual formations we have ever seen, the massive end of a fallen stalagmite

One uses a lot of imagination while observing cave formations. Under a canopy of limestone icicles, the solitary statue looked like an Easter Island moai to us.

This year-round spring spills into a pool surrounded by creamy red rocks.

This impressive sandstone wall looms over the delicate waterfall.

Near the cave, an old railway line still traverses the red sandstone cavern above the waterfall. The bridge was made by the Eiffel of the Eiffel Tower in Paris. Only hikers use it now while enjoying the trails of the park, but it ought to be a more accessible local attraction in the future.

Hot Springs in the High Plains, Aurès Mountains

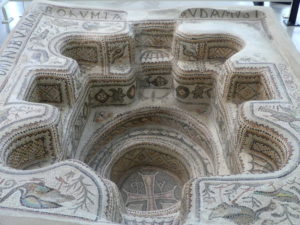

In this beautiful land of productive valleys and sheep farming within northeastern Algeria, one can hardly turn around without finding the remains of Roman cities. Those are the attraction for most western tourists, but we discovered a natural delight just as appealing. The Hammam Chellala thermal waters at Guelma create colorful ripples and icicles and steps as they spill over a plateau, a dazzling site adjacent to soothing baths using the same water. But we were so unusual a visitor that the local manager wanted to do a video interview with us for our feelings about the site. We gave it a five-star review.

Aures Mountain valley

We’re very exuberant about seeing the calcified drippings of the hot springs cascade.

Hot steamy rivulets pass through the whitened plateau over the cascade. As they head to the rear, they form large steaming pools which spill slowly over the edge.

We almost missed this extraordinary display of sulfurous steppes. Several people climbed that narrow walkway between the hot flows.

A flow of calcified stone from the upper right on the plateau demurely drapes the colorful curtain wall. That’s a peak of the Aurès Mountains in the distance at the left.

Algerian visitors enjoy the same colorful features we did, but also tend to follow a local ritual. As this man is doing, they boil eggs in one of the accessible sulfur hot pots, often purchased from the egg seller nearby, and then eat them together. This man’s family noticed our interest in the cooking and offered us one of their eggs, along with many smiles and greetings. It was tasty. Perhaps they also appreciated how concerned we were about the son’s zeal for lunging at the waters, which boil at 98 degrees C (208 F) at the surface.

An oddity…two hot pots at the surface show very different coloration. Below on the right is an old mound that was once actively spurting waters.

People wandered all over the hillside and plateau of the sulfur cascade, as the ghostly figure at the top suggests. Many skittered down a channel to see this feature. The whole formation seemed to result from a bit of clutter added by staff, but the impact on visitors justified the intervention. It does show well various calcified formations. And a mist of water droplets drips down engagingly from the cavern on the right.

View of the cascade from one side with a cloudburst of sulfurous mist at the top plateau.

Canyonland

The Rhouffi Valley is a richly varied desert landscape amid the grandeur of a mountainous region. In a day’s trip along its length, we oohed and aahed over its oases, the range of peaks pushed upwards by subterranean forces, its deep gorges, and its fade into sand dunes. At the heart of the valley, eons of geological change have left a vivid sandstone gorge to explore, Les Balcons, sadly now abandoned by its long-time cave-dwelling community.

A typical landscape here, with the desert edged by metamorphic mountains whose old layers have been shoved vertically into dramatic striations.

A broad valley en route to the Rhouffi Canyon community still flourishes with a palm tree oasis. We thought it elegantly graced by the bulbous mountains on the far side.

More desert and mountains in the Rhouffi Valley. Confused at first because signage along the way said ‘Ghoufi’ valley, we soon realized that was just another option for transliterating the name in English.

This mountain pass has quite a history to it, beyond its impressive gateway. It was a passage used by Roman legions in the 2nd century AD, and marked for future travelers with a Latin declaration carved into the rock. It’s also the site of a monument honoring those native Algerians who initiated the revolution for independence on 1 November 1954 by attacking French settlers here.

El Kantara means ‘the bridge’ in Arabic. And that’s the apt name of this small river crossing within a narrow pass carved by the menacing mountains around it. Those peaks rise up to 120 meters (400 feet) high, but seem to be splintering along their seams. The bridge spans eras as well. Long an important transit point for trading caravans, the bridge dates from the Roman occupation of 2000 years ago, but was rebuilt in 1862 by French forces under Napoleon III. A more modern railway cuts through the rocky pass now, above the bridge.

We are atop the pathway leading below toward the canyon homes of the Rhouffi cave dwellers, the cultural highlight of the valley. Along this ridge you can reach some of the brick structures of that old community, now abandoned. The valley floor, where the mosque sits, is 150 meters below (500 feet). We checked that dimension during our walk down and back up. They’re a bit hard to see, but on the far wall you can perhaps detect a number of entrances to the community’s caverns and brick houses. They’re just above the tree line at the edge of the sandstone rock, on surprisingly wide ledges some 75 meters up.

Several Algerian visitors asked us, “So how does this compare to your Grand Canyon?” We had to explain that the valley floor here was just 150 meters deep (500 feet), while the US canyon was 10 times as deep. But, to us, the statistics didn’t subtract from the beauty and history of the place.

This is the valley floor where a community occupied cave dwellings and brick structures for four hundred years. People lived on ledges facing this sweeping cliff and above the mosque to the right. Since 1970, the community has gone. Their life-giving palms were burned in sectarian conflict and the water flow that sustained their valley dried up.

The cave dwelling people lived on those ledges between the sandstone layers and the tree-dotted area. The largest structure there, however, was reportedly an Intercontinental Hotel from the mid-20th century, detectable across the canyon in the photo below. It was a rugged 5-star experience, with brick caverns reachable only by foot or donkey and shared bathrooms. We climbed the 75 meters (250 feet) up from the valley floor to see what remained: walls of stone and brick, but not much else.

So we can confirm that the views along the canyon were incomparable. The Rhouffi cave-dwelling community – and those who dared to stay at the Intercontinental Hotel – enjoyed this panorama.

As we drove away from the cave-dwellers’ canyon, the gorge narrowed and rose toward us, but the afternoon colors seemed even more spectacular.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Algeria, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)