One of the most exciting facets of Jordan is its wealth of mosaic floors dating back a few millennia to the Roman and Byzantine eras. From Amman to Madaba and Umm Ar Rasas to Petra, you could form a delightful tour of the country by just following a mosaics trail. Here are three groupings we discovered – and delighted in.

Umm Ar Rasas

A spectacular and enormous Byzantine mosaic lies on the floor of the St. Stephen’s church at Umm Ar Rasas, a UNESCO World Heritage site. The overall site contains a hodgepodge of Roman, Byzantine and Islamic structures from the first millennium AD.

As for this mosaic, many of the individual viney circlets of daily life in the central section, especially the grape-harvesting ones, have been pixelated by moving the little tiles about. The perpetrators were iconoclastic critics of these scenes. The borders, however, are mostly intact.

The inner border shows food, cornucopias, boating scenes and other amusing details to savor, such as a naked figure riding an ostrich. The second border shows the highlights of dozens of cities of the period. Jerusalem, Hagia Polis, is at the top left. And then geometric patterns and designs fill out the rest of the floor.

This detail shows a kind of icon for the walled city known as Philadelphia…the old one, now known as Amman, the capital of Jordan. That’s the panel for Madaba peeking out below it.

We were so engaged with this intricate mosaic that we spent an hour discovering more and more interesting detail.

Mt. Nebo

Mt. Nebo’s ancient church houses a restored 6th century masterpiece at the site honoring Moses’ doomed view of the Promised Land (see our post on Biblical Jordan). It is a surprisingly fanciful floor for a church, but full of the ordinary life of the time.

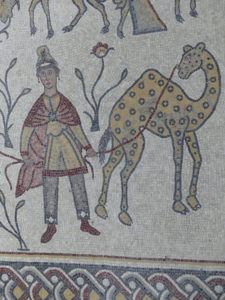

The closest row shows men in Persian attire with an odd array of animals; the second row shows a pastoral scene of contented sheep feeding on bushes; then a hunting scene quite vividly rendered; and then on top, two men defend their livestock from lions. Subtle effects came from using smaller pieces for shading and accent.

Zooming in, as we did in person to savor the mosaic, the photo lets you enjoy a detail of the Mt. Nebo mosaic, with the Persian camel herder and a bemused camel. Subtle effects came from using smaller pieces of varied tints for shading and accent.

A short distance from the main church at Mt. Nebo, at the small, rarely visited Sts. Lot & Procopius church, were some very fine additional mosaic floors from the Byzantine era. One highlight was this lovely scene of a peaceable kingdom. We paid the caretaker 1 JD, about $1.40, to open up the church and show us around, after wandering around a bit in search of the building.

As we learned at Mt. Nebo, scenes of daily life were quite common in the mosaics of the early church floors, rather than purely religious motifs.

The Lot & Procopius church also featured this charming vignette of fishing and boating.

Madaba

Madaba offers perhaps the greatest concentration of mosaic floors, long buried in the remains of both churches and villas. Many can be viewed in situ, while others needed to be restored and placed along walls for visitors to enjoy.

The most splendid of the Madaba mosaics lies on the floor of a 6th century Byzantine church ruin, an intricate masterpiece of geometric design.

A few centuries later, the Umayyad Muslims partly altered the original and added even more decoration at the edges.

This charming scene from one villa features Aphrodite on the right spanking an impish Eros, who is also involved in several other incidents to the left of the main one.

To the upper left of this panel are queenly representations of three cities – Rome, Gregoria and Madaba itself. Each city is rosy-cheeked with deft use of small tiles, and crowned with a set of local buildings.

At the Madaba Church of the Apostles, a barn-sized floor is covered with a massive set of mosaics dedicated both to the sea and to the four apostles of the Bible. We were so caught up in looking at them that a caretaker started to rinse portions off with “special mosaic water solution” so we could see the colors shine.

As we have learned, once we show a special interest in the features of a site, a local guardian wants to show us more, take us deeper inside, so to speak. The caretaker here didn’t find the same interest in anyone else that appeared during our stay.

Our man even let us slither carefully past columns at the very edge of the mosaic floor and tip-toe along some narrow breaks in the flooring so we could view less accessible sections up close. Trying to avoid stepping on the tiles was a bit stressful. Some of our hidden favorites were the Edenic scenes like this one, where we could study the strong contrast between the ‘cleansed’ sections and the rest.

We found these peacocks and sheep adoring an elaborate urn outdoors on an exposed floor at the Madaba Museum.

Madaba’s Map of the World at St. George

In the late 19th century, builders of the new St. George Greek Orthodox church in Madaba uncovered what was readily recognized as an extraordinary tile mosaic on the floor of an earlier church.

What they found was an astonishing 6th century Google Maps for Christian pilgrims to the Holy Lands. Though it only came in one language, Greek, it showed about 150 important towns and pilgrimage sites, running northward from the Nile Delta to Lebanon and eastward from the Mediterranean Sea to Arabia. It was originally about 20 x 7 meters in size (70 x 20 feet), but iconoclasts and earthquakes over time have much reduced it.

To give you a feel for the overall work, here is a video tour of the main part of the map, ending with Jerusalem. Up is east or Jordan and the Dead Sea, down is west toward the Mediterranean, left is northward, right southward.

With its large scale, not only could you plan your trip, but you could find your way around many of the towns based on their detailed representation. Most notable among these is the tiled representation of Jerusalem.

The label for the large ellipse of a town reads Hagiapolis Ierousa[lem] – the holy city of Jerusalem. The second line, Klir, means clergy. It’s really a street map, as the city walls, streets, gates and specific buildings are all identifiable. So archeologists have found it invaluable. Along the long axis of the town, for example, you can see the main street, the Roman cardo, neatly colonnaded in the tiles. That, together with a church shown on the map, was unearthed within Jerusalem itself in 1967, precisely where the map placed it. Similarly the exact location of the gates have been confirmed as recently as 2010. To the city’s immediate right (south) is the label for Bethlehem. Below it (west) is another detailed townscape, Nikopolis. Above Jerusalem (east) is the Dead Sea, with a portion of a boat rowing about.

The presence of one particular building in this map dates this map after 542; and the absence of other structures built in 570 also delimits the time frame of its creation.

Overview of the main part of the map minus the panning about, with Jerusalem in the center right.

Up from there is east or Jordan and the Dead Sea, down is west toward the Mediterranean, left of Jerusalem is northward, right southward. Iericho (Jericho) is toward the camera from the Red Sea. Note some of the fanciful features in Jordan, like the fish trying to escape the Dead Sea by heading up the Jordan River and a gazelle fleeing a defaced image of a lion. Bridges across the river are placed correctly.

A second portion of the map continues on the other side of a support column for the church.

The waterways show the Sinai with the flows of the Nile through its delta into the Mediterranean Sea.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Jordan, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)