In brief: The native son of Zaragoza, Goya could capture the light of the spirit and the dark of human failings. The works viewable within the city show that range.

The artist Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (1748 – 1828) grew up in the city of Zaragoza, so he is especially honored there as the greatest Spanish painter of his time. Son of an artisan adept at gilding, he rose from the middle class to become court painter for the Spanish kings and nobles in Madrid, executing many portraits and courtly ensembles.

While his father managed ornamentation for the noted Pilar Basilica; his esteemed son later painted the dome at the center of its ceiling. The Goya Museum in the city honors him in a former palace, with a fine collection of his engravings and oil portraits, including an early self-portrait. Other Spanish churches and museums around the world treasure paintings by him. Increasingly over the years, he seemed particularly observant of the dark side of people – their pretentiousness, moral failings, and ruinous commitment to war’s horrors. In later life, much of his work brought these views to the fore.

In his late 20s and already at the court in Madrid, Goya painted this self-portrait, now featured at the Goya Museum. His penetrating, self-confident gaze at the viewer might have been a form of business card. With it, he could demonstrate his skill at catching personality for the nobles who wanted their portraits done.

Saint Augustine (1796 – 99) was one of the most important writers and thinkers in creating the foundations of the church. When Goya painted this stunning portrait at about age 50, he was working on commissions for churches on the one hand and, on the other, producing many satirical and fantastical drawings critiquing the moral failings of his day. Goya portrays Augustine quite complexly, bathed in golden light but weighed down by the voluminous robes of his responsibility. He has just stopped writing, and looks upward with an ambiguous expression. Is he struck by inspiration from the heavens or troubled in his search for the way? Is his left hand receptive or trying to grasp at some thought? Goya surely recognized the challenge of philosopher or artist, wrestling with ideas, often inspired, yet sometimes unsure of direction.

“Arrest of Christ” (1798) was a painting we found in the collection of Toledo Cathedral near Madrid. It’s considered very typical of late Goya. The strong contrasts of dark and light underscore the more thematic contrast between the intense press of the beast-like captors and the eerily glowing Jesus, who serenely, if sadly, accepts his fate. Goya painted this for an altar whose candle-lit base would accentuate the contrasts.

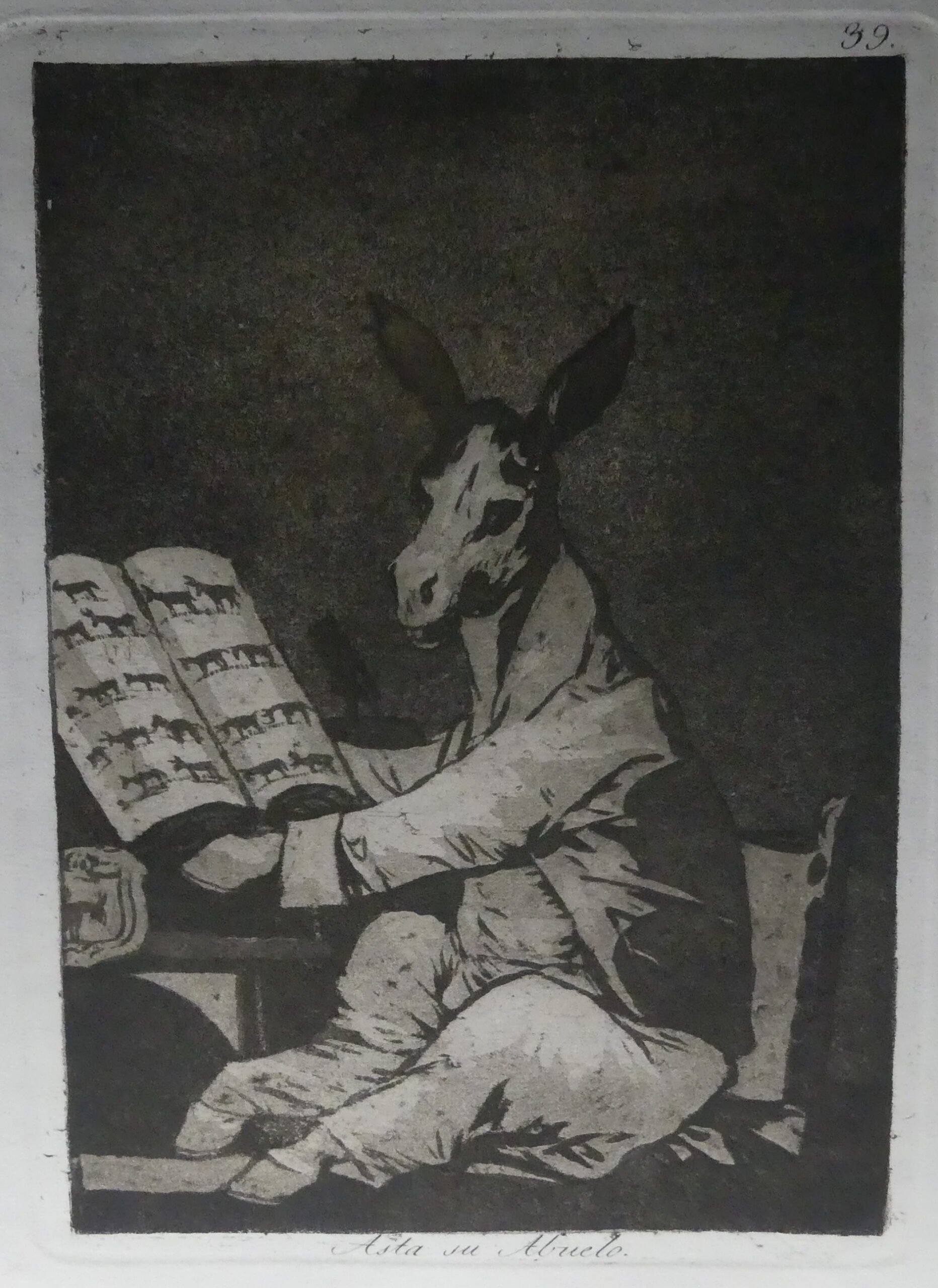

“And so was his grandfather” Here Goya ridicules the hereditary nobility, a group Goya knew well at court. With its family crest on the bottom left, the well-dressed ass stares defiantly at us, showing off his family tree in the book – a long line of asses.

This etching is one of 80 Caprichos (Caprices) in the series from 1798-99, all of which are displayed at the Goya Museum. As here, they include satire and disdain for contemporary folly as well as fantastical, nightmare images of mental states that Dali certainly admired.

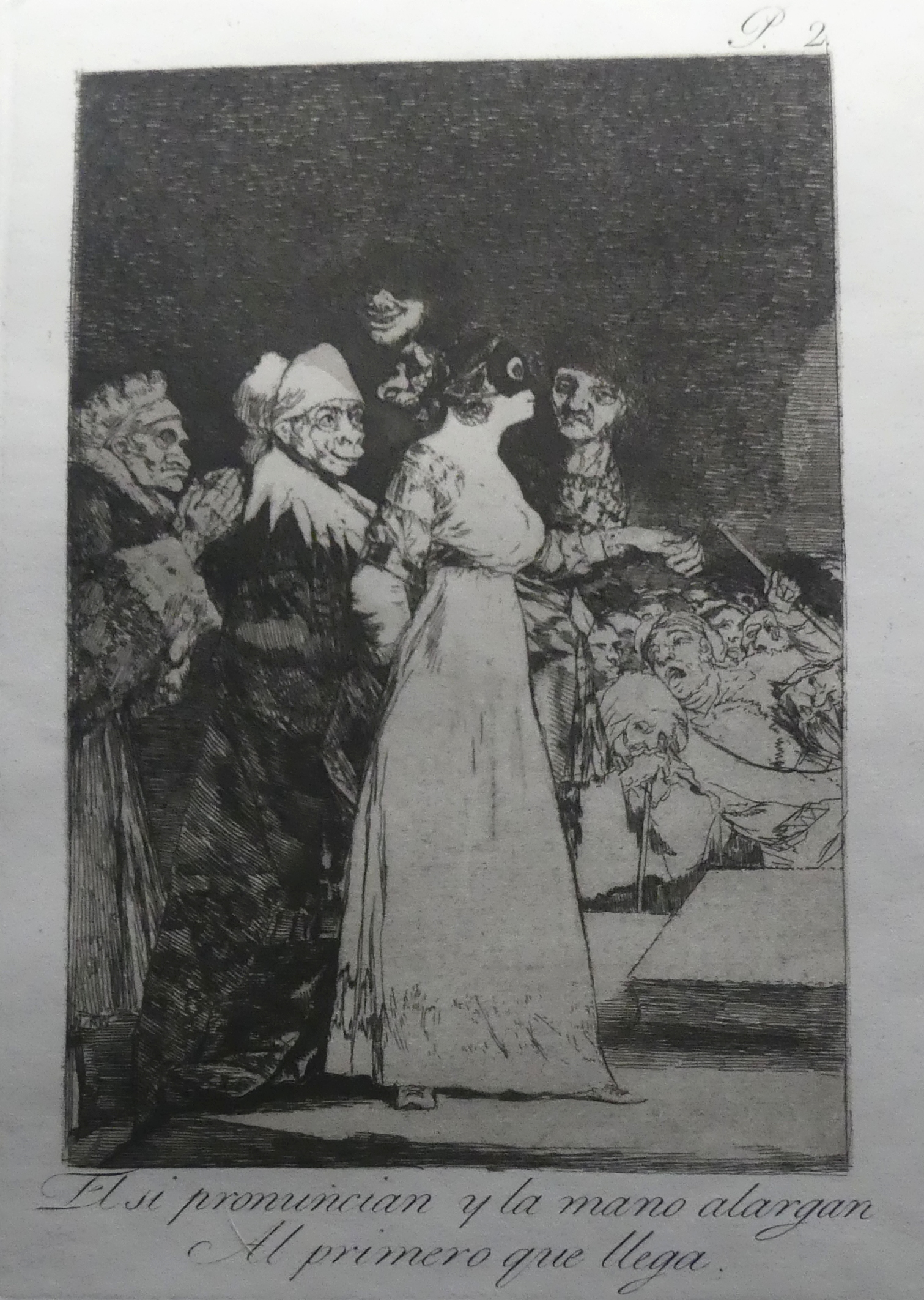

“They Say Yes and Give their Hand to the First Comer,” another of the 80 Caprichos,shows a young woman led almost sacrificially into the arms of an old lecher with a gallery of people turned grotesque by their immoral acceptance. Wealth has the power to corrupt everything.

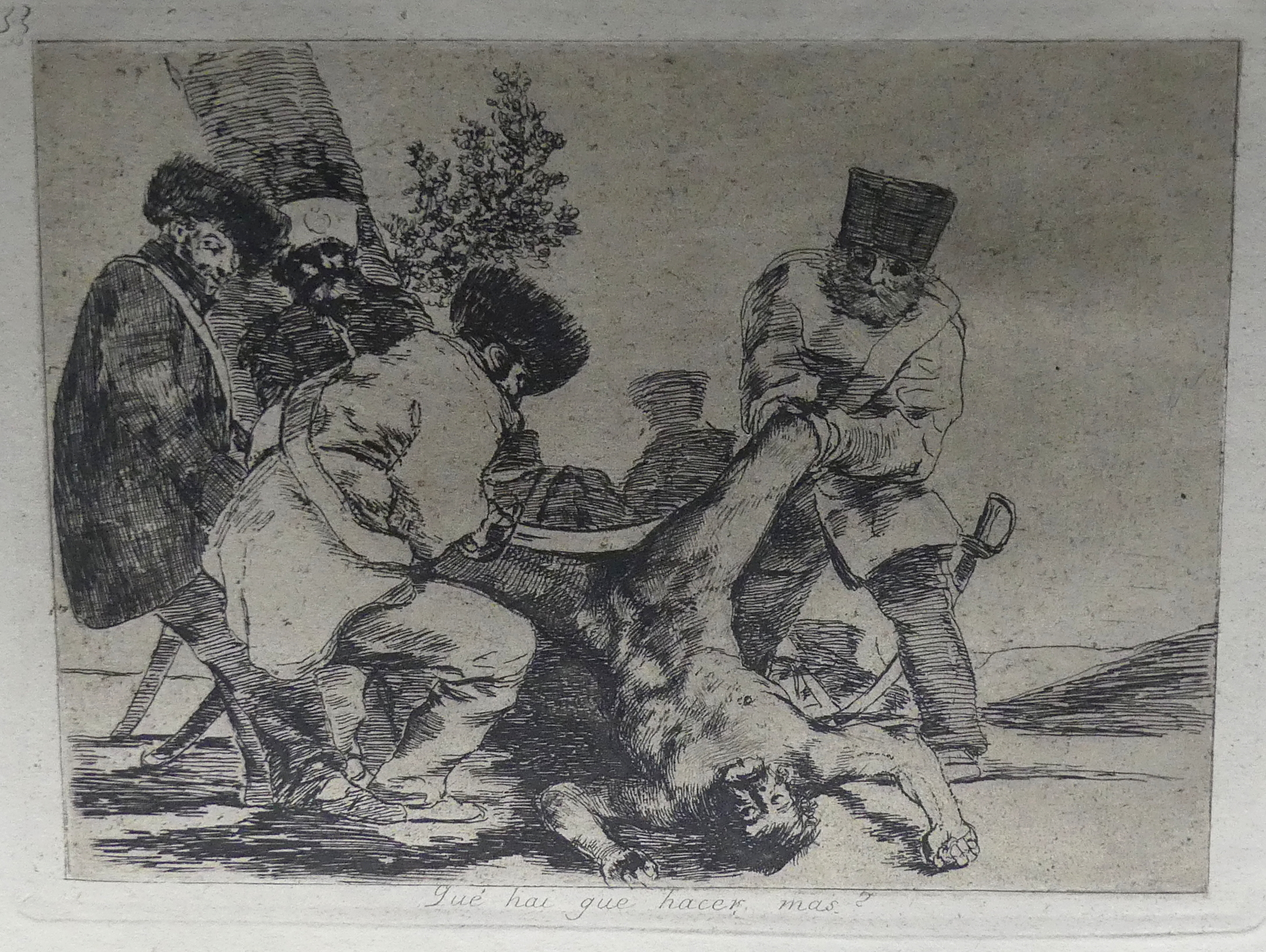

“What more can one do?” is from another series of etchings about war and the depraved behavior of empowered men. In these, Goya illustrated many forms of oppression by the French, including killings, rape, and destruction. Here, in a strenuous image caught with minimal lines, Goya recalls the killing of Christian martyrs in religious paintings, as French soldiers prepare to quarter a helpless Spaniard starting at the crotch.

The Second of May 1808 in Madrid or The Charge of the Mamelukes (1814) is a remarkable sketch in oil that hews closely to Goya’s more finished and famous work with the same title. In both, he celebrates the valor and ultimate victory of the poorly armed Spaniards against Napoleon’s occupying army. The captured moment is the onset of their revolt, as the French cavalry attacks. Here the chaos and danger are evident, with the dominant French represented especially by the central attacker on a white horse. But the red slash of the falling attacker just below him and the fallen one on the bottom left remind us that the Spaniards would push out Napoleon’s forces.

Goya personally observed the horrors of oppressive power and murderous occupation, and often depicted these in his art. Freedom from such afflictions was paramount to him. And we could not fail to see the parallels to modern conflicts and invasions.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Spain, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)