In brief: The bountiful Kakheti region is not just sloshing in wine, the major product now. It’s overflowing with secular and religious history as well.

The last major region we aimed to see in the Caucasus was Georgia’s wine-making center, Kakheti. Even though we fit the visit into the less robust time of winter, we found plenty of wine to enjoy, history to uncover, and scenic beauty.

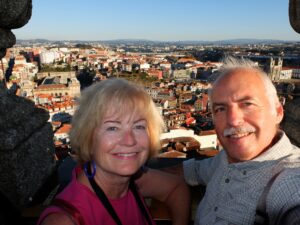

The heart of wine production here is at the Alazani Valley, only two hours drive from the capital Tbilisi. Countless wineries dot the long valley, some 100 kilometers in length (65 miles), along which endless rows of vines and fruit trees grow. The charming walled town of Sighnaghi toward the southeastern end of the valley has a special attraction in this special place, hanging some 300 meters (1000 feet) above the wine-soaked valley and its frequent winter fog. Because of the town’s heavenly location and brilliant photo ops – as well as some local romantic legends – Sighnaghi is known as the City of Love. So it’s a magnet for newlyweds and even old-ey weds like us.

Alazani Valley

The names of nearly every town in the Alazani Valley were familiar to us as varieties of Georgian wine, just as in France or Italy. We visited one larger winery outside of Sighnaghi, Ampelo, dating back to the 1800s. Beyond this gate were some of the winemaking facilities they ran, a dining room, and a hotel that was nearly empty in the off-off season. They insisted that we taste about a dozen of their products.

It seems that nearly everyone in Georgia makes their own wine; and that is certainly true here in wine country. Here we are enjoying the good life with our host at the Traveler Restaurant (and hotel) in Sighnaghi after a short private tour of his small private winery, or “marani.”

Our host keeps several years of white and red wine maturing in the clay vessels marked by the circular openings in the ground, and bottles his own. The clay vessels are called (the virtually unpronounceable name) “queuri,” and some older examples are displayed at the upper right. That name also represents the traditional Georgian wine method, some 8000 years old: the grapes are crushed along with the skins, seeds, twigs, and who knows what else before fermenting in the clay pots. To serve us some wine, our host just dipped our glasses into the pot that was all ready to drink.

On our first night in town, we just happened to pick his place, more a large dining hall than a formal restaurant. We so loved the food prepared by his wife, let alone the good wine, that we returned every other evening!

Sighnaghi

Sighnaghi’s old center and hillsides are ringed by 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) of walls like these, with 28 turrets. Within you walk or drive on roads laid with stone. That lovely spire tops the stonework St George Basilica.

No words. We awoke every morning to this vista over old Sighnaghi. On this day, the fog blanketed the broad Alazani Valley, and highlighted the snowy peaks of the Caucausus Mountains separating Georgia from Russia.

Wintry fog hovers over mountains and vineyards in the Alazani Valley

No words. On this day, the sun swept wisps upward toward old Sighnaghi from the broad Alazani Valley.

A back street in Sighnaghi demonstrating its traditional stone and brick construction with wood porches derived from Persian influence.

Sighnaghi – a symphony of brick and stone along a ridge of its hilltop location.

A feast – with much wine – in the Georgian countryside painted by Georgian artist, Nikos Pirosmani. He was discovered late in life as a remarkable painter in a folk style reminiscent of Grandma Moses or Rousseau. He had begun with signage and posters for businesses, but sadly died in his 50s in 1918. His work reveled in the varied people and culture of Georgia with a wry, but fond feeling. He did many portraits of tradespeople and historical figures, though landscapes and group scenes that we have seen elsewhere are particularly thoughtful. Sighnaghi’s city museum has an extensive collection of his works on display. (sorry for the bad angle!)

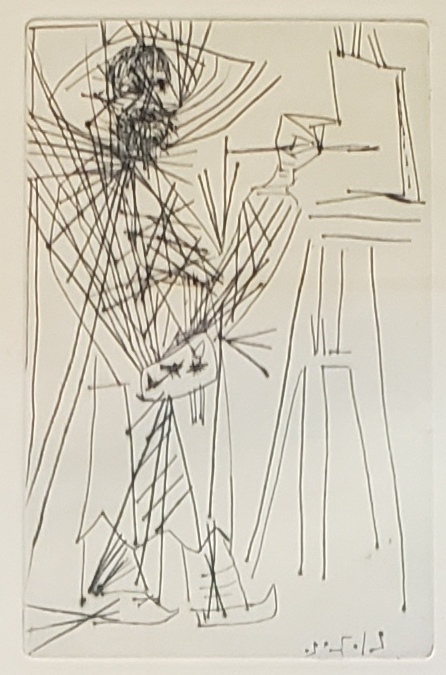

Picasso, remarkably, near his own death more than 60 years after Pirosmani’s, sketched his understanding of Pirosmani’s artistry in this explosive portrait of a painter who consists merely of his own lines and strokes. The original is here at the Sighnaghi museum.

And just one more…with the backdrop of the snow-topped Caucasus Mountains.

Gremi, Bodbe, Telavi

The bountiful Kakheti region is not just sloshing in wine, the major product now. It’s overflowing with secular and religious history as well. (To experience the David Gareja monasteries that we visited during our return to Tbilisi, click here.)

Gremi

After Georgia split up into principalities in 1466, Kakheti became a very powerful kingdom under King Georgi. Its capital was Gremi.

There we toured the fascinating 15th to 16th century castle, bell-tower, and Church of the Archangels castle – which have perched atop a hill since then. On about 40 hectares of flat land around the hill spread a commercial and religious complex that thrived for 150 years until it was destroyed by the Shah of Iran in 1616 after bitter conflict.

We climbed the dark stone tower at Gremi on a twisting narrow staircase.

Part of the 16th century frescoes within the church at Gremi. This shows King Levan, or Leon, cozying up to Mary and Jesus by offering them the church. Until 1574, Levan ruled the Kakheti region for 54 years.

Among the kings who preceded him, after Georgi I founded Gremi, was the inept and warlike Georgi II, known as George the Bad, the Mad or the Evil. Levan, by contrast, brought peace through wise management and political skill as well as prosperity through Silk Road trade. Levan also built churches and monasteries throughout the country while also supporting Christian missions in both Jerusalem and Mt Athos in Greece.

This 12th century tile discovered at Gremi featured a Star of David. Christians, Jews, and Muslims lived together and traded here for centuries.

A small church in the wooded valley beneath the hilltop castle at Gremi shows its ungainly evolution from one building into three. Around it the sizable capital city of Gremi thrived for centuries.

A clay tablet on the tripartite church at Gremi displays multiple crosses festooned with medallions and vine-y decoration befitting the wine region nearby.

Bodbe

The rulers of Kakheti, however, preferred to be crowned some 70 kilometers away at another hillside site near the walled city of Sighnagi. That place is Bodbe, a revered monastery dedicated to St Nino, the 4th century woman who turned Georgians into Christians.

This is the main church at Bodbe, dating from the 9th and 11th centuries, but extensively upgraded and rebuilt over the years. It was particularly impressive emerging from the dense fog.

Bodbe is still an important pilgrimage site because of St Nino, who is buried here. She is the renowned home-grown saint of Georgia, who brought Christianity in the 4th century. Bodbe emerged as a monastery and major theological school through the 18th century. It was then neglected until, fittingly, the complex turned into a nunnery during late 19th century Tsarist rule.

17th century frescoed walls of the chapel at Bodbe. The large panel is a Last Judgment, where the white-clad good guys at the bottom left are being shepherded to grace while dark devils whip the sinners on the right. On left of the arched ceiling above, you can just see Eve offering a tempting treat to Adam and, on the opposing panel, an angel driving the pair out of Eden.

Telavi

Toward the western end of the Alazani Valley, at the edge of a mountain range, lies the historic town of Telavi. This had been the medieval capital of Kakheti Kingdom. Then, after the fall of Gremi, it became the capital of eastern Georgia through the late 18th century reign of the enormously influential and reform-minded King Erekle II. A kind of folk hero, Erekle – or Patara Kakhi (‘Little Kakhetian’) – still represents the people’s aspiration for freedom.

The imposing entrance to the palace grounds built by Erekle II. The walls surrounding the huge grounds have remained solidly in shape, as are a church complex and the ceremonial hall of the king within the grounds.

The church complex at the far end of the palace grounds. Because of the reverence for the king, the church is considered a very auspicious place to be married. A huge wedding party appeared while we were visiting to do their rehearsal.

The 18th century greeting hall of the king. That is Erekle II in the picture, who turned Georgia from its Persian ties to become more modern and European by allying with Russia. Soon Russia subsumed Georgia instead.

A portrait of the builders of a structure at Telavi from the 9th century as the town grew in importance. This was in the small, but intriguing, museum on the palace grounds.

The architecture of Telavi’s main streets shows how it prospered in the 18th century, but these picturesque wooden buildings recall the influence of Persian styles, as in the center of Tbilisi.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Georgia, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)