“My baby does the hanky panky” – Tommy James and the Shondells

Yes, it’s an outrageous pun, but somehow we couldn’t help but think of music by the American Shondells from the 1960s. Yet we were far afield in India on serious business. We were assiduously touring one of the country’s most notable and notorious set of World Heritage monuments, the stunning art and architecture of the pink sandstone temples of Khajuraho, built by the kings of the Chandella, not Shondells, dynasty.

For about three hundred years, from the 900s to the 1200s, this dynasty held sway in north central India. Their wealth must have been extraordinary for they could afford to build temple after temple around this now tiny town, each of which are saturated with extraordinary sandstone carvings.

The temples number over a dozen, spread over a few kilometers in all directions, divided geographically into a western group adjacent to the town, and an eastern/southern group a few kilometers off. Each was intended to honor one of the gods of the Hindu divinity, mostly Vishnu. Others are dedicated to Shiva the destroyer and creator (and his seriously fearsome representations), Surya the sun god and four-headed Brahma.

The temples were places of worship, as is the more contemporary temple nearby, full of chanting prayers on the morning of our visit. And the temples themselves physically represent the human attempt to understand the divine and connect with it. They are prayers in stone.

Of course, we are foreigners to much of the religious significance of the temples, as our 10 times more expensive “foreigner” ticket underscored. But, with some living and recorded guidance, we found so much to admire and connect with.

The largest and most elaborate of the temples differ somewhat but share a common style and several characteristics. The temples rest on raised platforms that are now mostly unadorned. Up another set of stairs, a visitor passes through the temple entrance and contnues westward through three or four halls, each progressively darker and topped by a heavenly dome. You then reach an inner sanctum within which stands a statue of the god to whom the temple is dedicated, facing east, along with his appropriate attendant figures. For example, above the inner doorway of Chitragupta, dedicated to Surya the sun god, three figures represent the sun at morning, noon and evening. Under the god’s statue you can see the heads of seven horses, which pull the chariot of the god across the sky.

On the outward-facing walls of this inner sanctum, barely visible in the dim light, meter-high figures are carved in the stone. These include gods and consorts, the graceful presence of courtly women attendants, as well as mythical creatures.

Back outside, the whole structure ascends to heaven. A spire rises above each of those temple hallways, linked together with the next spire, and narrowing as they climb skyward. Each spire consists of numerous tiers of stone plates to start and then tile-like stonework till the top. Viewed from a distance, the temples are sublimely beautiful. Viewed up close, they astonish in their detail.

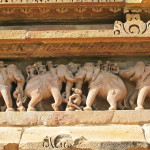

We paid most attention to five of the temples: three in the western group (Lakshmana, Kandariya Mahadev and Visvanatha) and two in the eastern group (Vamana and Javari). Each is wrapped around by three levels of meter-high friezes and bas-relief sculptures, typically separated by narrow bands that are decorated with animals and scenes from the life of the period. All in all we must have browsed, stared and partly photographed several hundred meters of the bands at these temples – an artistic overload almost.

There was, however, a kind of rhythm to it all. Imagery repeats, both on an individual temple and across temples, for later ones flattered their predecessors by imitation. As the splendid audio guide for Khajuraho noted, the figures could be categorized in five types: the ones we had seen at the inner sanctum (gods, attendants, mythical and real creatures) as well as common people and beings related to the gods. The richness could be overwhelming, but it was never boring, as there was always some new thing to notice as we explored.

The most notable temple. Lakshmana, adds a further layer of bas-relief around its extensive base. This band features on its northern side military scenes, replete with elephants, weapons, horsemen and warriors – miniature Elgin marbles or oversized Bayeux Tapestry episodes emerging from stone.

On the southern side, depictions of daily life take over. Here the soldiers seem to return home to enjoy the more domestic and even overtly sensual rewards of peace.

And that sensuality seems to exert a more powerful grasp on contemporary imaginations than the religious and spiritual intent of the temple’s builders and creators. Guidebooks and our audio guide give disproportionate attention to the vivid, extensive and no-holds-barred sexuality of so much of the sculpture.

Even on the domestic side of that great bas-relief around Lakshmana, especially near the stairs up to the temple, people conjoin in various positions, not necessarily with other people. In one section, women look away from a union that they consider too obscene.

Up on the broad bands surrounding Lakshmana, Kandariya Mahadev, and most of the other temples, there’s a lot of hanky-panky going on…amid the much greater number of more reverent depictions of divine beings. The gods and their consorts are perhaps the most demure, with his hand delicately crooked behind her back and onto her breast.

The attendant females strike provocative yoga-like poses, while they adjust their hair or peer into the mirror or apply makeup. Scorpions on their thighs signal lust.

As our eyes wander across hundreds of meters of panels and sculptures, suddenly a naked group couples before you. Or we see a complicated orgy of multiple partners in what prove to be tantric positions.

There are many explanations of what the Hindu Chandellas and their sculptors were thinking about in mixing the sacred and the profane together. The most compelling one to us was that they saw the union of male and female principles in the universe as the greatest end for heaven and earth. Even today, the representations of this – the male lingam set within an encircling female yoni – are a most powerful locus of Hindu worship. The design of the inner sanctum at the Khajuraho temples, a domed structure surrounded by a circular passage, channels that power.

The erotic expresses, in perhaps a Darwinian sense, the essence of life as lived on earth – the potential for procreation. But the erotic is also the essence of life as desired after death and in the heavens, where all division is unified. As our audio guide pointed out, it’s not by chance that the largest and most complicated sexual acts are on the exterior panels that line up, inside the temple, to the junction between the outer halls and the inner sanctum of the temples. Something special must happen as you approach the gods to whom these structures are dedicated.

We were reminded of the more metaphoric versions of such hanky-panky in a type of medieval Western art that is, perhaps unsurprisingly, contemporary with these temples. This is the art of courtly love.

A diverse and wide-spread phenomenon, the idea of courtly love turned a barely disguised desire for sexual union into a displaced form of desire for union with the divine. In literature, the French Romance of the Rose is one of courtly love’s most notable literary representations, but just one of many. The aim of the “pilgrim” there is to penetrate the inner “garden” where the maiden and heaven await. There is often a tower in that garden, another lingam set within the yoni. Paintings duly and demurely repeated the idea. Fairy tales later picked up the same ideas (Rapunzel, for example).The trope was so powerful that it’s found far afield from the literature of courtly love. In the real and ersatz science of alchemy, for example, the goal is the union of male and female principles in the most yoni-looking of containers.

As we left the temples, east and west seemed very connected. The bold, overt sexuality of the art might be different, but we foreigners felt right at home.

(Also, for more pictures from India, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the India itinerary page.)

It looks like you were the only people around, or is that tricky photography?

Even though we were at the temples early, there are very few tourists in India (except up north in the mountains) because of the intense heat and the oncoming monsoon season. It was pretty easy to wait out the few hardy visitors who dared to step into our picture frame!