In Brief: You feel the tug of heavenly thoughts and earthly concerns across the town of Évora.

The Se, or Cathedral

Evora’s imposing Cathedral sits at the center of this World Heritage city atop its highest point. Yet from the main approach, it is somewhat modestly tucked into the corner of a plaza, peeking discreetly from behind some tall trees.

Two large stolid towers flank the main Gothic entrance in a corner of the church square. The only figures at the entrance are two sets of graceful marble apostles. A pair on this side seem to be more curious about visitors than religious matters.

The Cathedral took shape over two hundred years starting in the 12th century, but then added gorgeous elements for another 200 years and more – a compendium of Romanesque, Gothic, Manueline, and Baroque styles. Though it is dedicated to the Virgin Mary, its fort-like appearance recalls why it was built, to herald the 1166 triumph over the Moors by the local hero, Giraldo the Fearless.

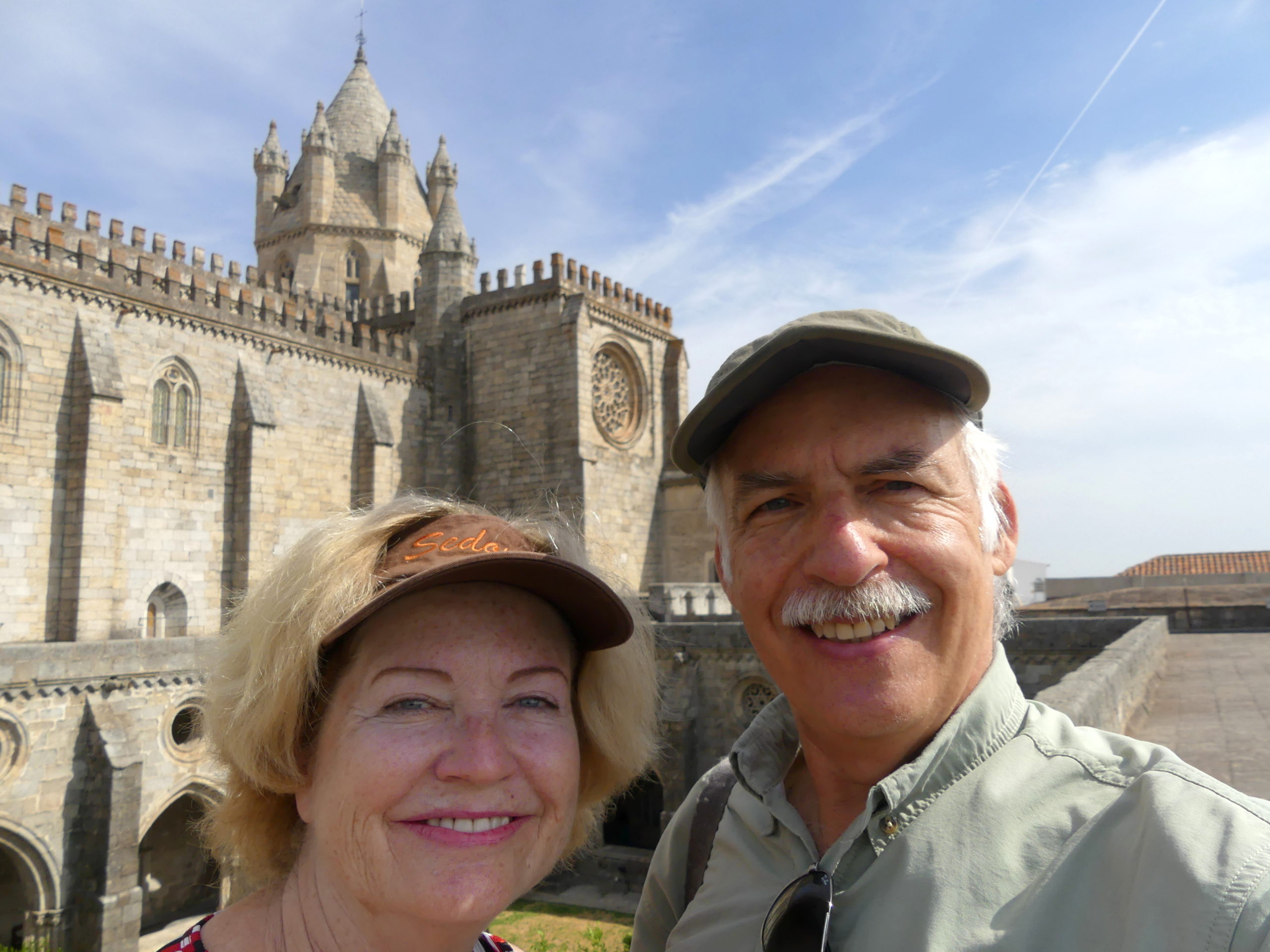

The Cathedral from its backside is perhaps even more impressive, though still somewhat austere compared to other European Gothic churches. The addition on the left is indeed marble, not just along the walls but also forming the entire terrace on top. When we walked on the roof, that terrace made quite a contrast with the stonework of the older portion of the church. In a way, it celebrates one of the region’s important products. Marble quarries spanning dozens of kilometers still yield huge quantities of the stuff today.

Heading inside the Cathedral, we found something completely different.

King John V paid good money to re-do the main chapel and altar of the church in the early 18th century. His favorite style, as designed by the man who created the glorious monastery of Mafra, was very fashionable by then, though his Roman Baroque conflicted a bit with the medieval nature of the church. The colorful renovation is highlighted by marble arches and columns of various tints.

But the light remained familiar to fans of the Gothic: this simple but luminous rose window shines beyond a more contemporary, huge glass chandelier.

A short passageway out of the church interior led us to the four aisles of its Gothic cloister. Each corner featured one of the four Evangelists.

We couldn’t figure out which this one was, either from the inscribed text on his book, the decoration beneath his feet, or what looked like a weird monkey above his head.

The 14th century Gothic cloister from above after we wriggled up a short spiral to the upper level. Each of the small rosette windows featured a different geometric design in stone. From there, despite frying in the torrid sun, we also enjoyed a fine view of one of the Cathedral’s rose windows and its crown-like tower.

A second climb up that tower took us to the roof above the main aisle, and views over the city. One of the most impressive elements of the church is this octagonal cap to the tower, a regal crown rising over the center of the cross-shaped interior. In addition to its rose windows, the array of smaller windows illuminates the interior dome throughout the day.

Evora’s Carthusian Monastery

A ten minute walk north of Évora, along its low-lying aqueduct, hides a little treasure – a former Carthusian monastery dating back to 1587 just after construction of the aqueduct. Our hosts clued us in that the monastery was now newly opened for weekend visits by the public after an heir of the Cartuxa (“Carthusian” or Ordo Cartusiensis) wine scion restored it.

The dazzling marble exterior of the Cartuxa church, also called Scala Coeli or, roughly, stairway to heaven, provided a grand portal to the community of hermit monks known for their modest behavior.

In the monastery church, this intricately carved and gilded wood altar captured our attention even though the dark wood of the choir stalls flanking it were stunning.

This pool and fountain are at the center of the cloister, accessed by lanes hemmed in by bushes, feeling almost like a meditative labyrinth. The arches of the corridors surrounding the cloister garden mark the locations of the small cells where the hermetic monks spent most of their time, as if they were remote caves. The design made clear how their lives centered on solitude and silent contemplation. As is the cat’s in the foreground.

These figures dribbled from a smaller fountain at a little plaza just inside the main entrance. The plaza’s encircling corridors were lined with azulejos, the omnipresent Portuguese blue tile work.

Wines have long been associated with monasteries, so in a way we were not surprised to find that the Cartuxa company’s main winery is nearby, recognized in Portugal for the high quality of its product. For a more secular experience, its classy enoteca in town offers these wines and very fine food in the same central square as the Cathedral.

At the enoteca, this local dessert specialty finished off a delightful meal paired with a refreshing bottle of vinho branco. It’s fittingly (and fatteningly) called “natas do céu” (cream from heaven), a divine combination of lemon, cinnamon & vanilla egg cream, mousse and crumbled Maria cookies.

We made a second pilgrimage to the enoteca for the kind of meditation and contemplation it offered.

Memento Mori (Remember that you die)

It’s hard to imagine that the lightly clothed tourists and family groups visiting the Évora ossuary heed the ancient warnings posted within. “We, the bones that are here, wait for yours.” We too had entered more for the spectacle than the messages.

The thickly packed walls of its long dark chamber display thousands of monk bones, while others are arranged decoratively around the vaulted room.

A monastic cult dedicating itself to the Souls of Purgatory collected the bones here in the early 16th century from various burial sites. Its gracefully painted ceiling seems more like Paradise than Purgatory – were it not for the row of skulls lining the vault arches.

Over the entryway to the gallery hangs this more fanciful use of the various bones of the body, and perhaps a more pointed message than the crammed walls.

However, to us, nothing here rivalled the impressive ossuary at Kutna Hora in the Czech Republic, where bones were endlessly arranged as familiar objects, emblems and even chandeliers – a kind of bony Disney World.

It all might seem a bit creepy or gruesome to a modern mentality. But then as now you’re supposed to meditate on how trivially we spend our time and how soon we die. As a poem in the skeletal chamber tries to warn us, before we bustle from the dark ossuary into a sunlit day: “Where are you going in such a hurry, traveler?/Stop…do not proceed any further; You have no greater concern/Than this one.”

The ossuary is the main attraction for tourists to pay the combined admission to the church (Adults, 5 Euros). But the renovated church itself has other charms, including this tile representation of the Stations of the Cross.

Upstairs, a small museum displays a few treasures while the extensive Canha da Silva international collection of Nativity scenes (as exemplified in our Museums post) takes up the top floor. Plus you can enjoy a panoramic view of the town from that veranda, as you can see in a future post.

Surely, though, if you attend to the message of the ossuary, you might come right in here for some prayer. This is the altar and main aisle of the medieval Sao Francisco church, home of the ossuary.

Its extensive renovation about five years ago left the exterior quite plain, but revivified the interior space including its marble altar with a vaulted roof.

Or head across town to the enoteca for its earthly taste of heaven.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Portugal, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)