In brief: Though Rome largely obliterated the Punic empire, some towns survived through collaboration. Excavations from necropolises around Carthage let us glimpse its culture and beliefs.

For about 700 years, the Punic people around Carthage (now Tunis) built up a wealthy and powerful empire. The Punic people originally came from Phoenicia (modern Lebanon) named for the valuable purple dye they produced out of certain sea shells. After hundreds of years of bloody wars ending in 146 BC, the ascendant Romans effaced nearly all their buildings and records. (See our previous post about Carthage itself.)

What we know of them comes from discoveries by modern archeologists who dug deep below the Roman surfaces that replaced the Punic sites. Or who found the few towns that avoided Roman destruction, like coastal Kerkouane on the jutting Cap Bon peninsula at the southern edge of the bay of Tunis. At that UNESCO World Heritage site, we could see remnants of the old Punic town as well as many treasures buried with their dead for use in passage to the afterlife.

Kerkouane

A vista over the seaside town at Kerkouane, the UNESCO Heritage Punic town that outlasted Carthage, though no one knows the real name of the place. In the center at the front, at the inverted L shape, we could see a very unusual feature of such an ancient house, one repeated in other houses across the town.

It’s a stone bathtub that you sat in, accessed from the open section to its right, plus a square sink adjacent to it. The circle to its front and left was part of the drainage from the “tub.” Each home was two or three stories tall, but just the lower level and foundations remain. The town flourished from making that same dye for which the Phoenicians were named, as well as trade.

Punic wall construction at Kerkouane differed from Roman methods. Some buildings used bases of large stones, but most of the homes used large stones only to anchor the corners and support the weight of several floors. The walls here used a herringbone pattern of flat stones for added strength.

Museums at Kerkouane and another noted Punic town, Utica, illustrated the life of the Carthaginians through artifacts found mainly during excavations of burial sites. Like Kerkouane, Utica was not destroyed by the Romans for these two towns collaborated with the Romans, but eventually they too were buried under Roman development.

Archeologists have exhumed large portion of a Punic necropolis at Utica, uncovering so many treasures in the tombs. Notice on the upper right, the wall which shows the level at which the Romans built their new town relative to the old Punic town.

Some of the treasures we saw:

— A startling altar piece from the 3rd century BC found in the temple area of Kerkouane. Two griffins on either side attack a deer in the middle.

— These amphora and goblets at Utica date from the 6th century BC, the result of trade with the Greeks or their cultural influence. Similar ceramics were on display at Kerkouane.

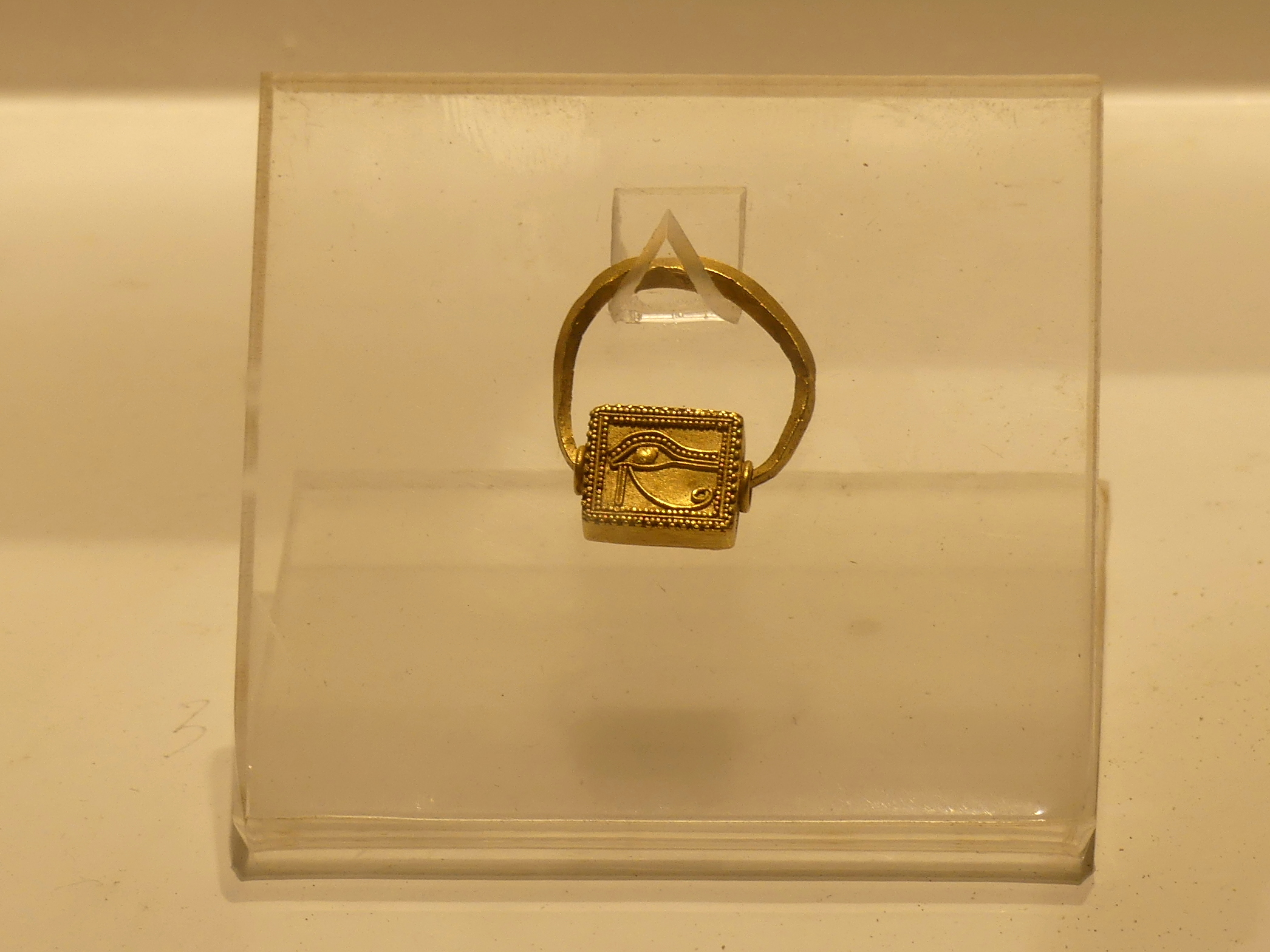

— A ring from a Kerkouane tomb showing the Egyptian eye of Horus, another connection of the eastern Mediterranean with the Punic people.

— A gourd in the shape of a wild boar at Kerkouane. Others on display with tinier spouts seemed to be vessels for young children to drink from.

Death and Tanits

The most fascinating discovery we made was the Carthaginians extensive use of an emblem called the tanit.

This is one of many markers of sacrificial offerings found in Carthage and common to the Punic people, all about a half meter high. The main figure below is the tanit, an emblem of fertility and good fortune.

Symbolically it represented the goddess Tannit who, like the Phoenician Astarte (Ishtar) or Roman Juno, delivered bounties as well as success in war. The crescent moon above is also associated with those goddesses.

These markers were discovered all over Carthage and gathered below for visitors to view. Priests would set them above buried urns holding the cremated ashes of a sacrificed animal. Each stele bore a symbol (doorway, vase, divine figure, tower, etc.) representing the goal for the sacrifice, some kind of good fortune or a heavenly gift.

We even found the tanit in situ at Kerkouane, notably in this surprising mosaic floor of a Punic house. Light colored stones were set in the clay-colored or dark flooring, forming not images or a pattern but, to us, a feeling of looking at the starry skies. And there again was the symbol of tanit at the inner doorway, apparently a kind of totem to ward off evil from the house.

The goddess Tannit herself is represented in each of these two terracotta statues, from an inland sanctuary at Thinissut, near Kerkouane. The Punic people imagined her as a lion-headed warrior as well as bringer of fertility – unlike the much more reductive symbol of the tanit.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Tunisia, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)