The Gambia is a sliver of a country, essentially several hundred kilometers of the Gambian River, a ragged slice out of the middle of Senegal. Why, we wondered.

We discovered that the British in the early 1800s secured the river mouth on the Atlantic, as well as upstream, to stop the slave trade by the French and others from the African coast. They kept control of the country until 1965 when The Gambia became in independent member of the Commonwealth. As a result, though its people share tribal origins with the French-speaking Senegalese, Gambians speak English instead – and still use the British three-prong electrical outlets.

After independence, Gambians suffered economically and politically under an oppressive military leader until 2017. Yet we found them, newly independent and democratic, to be surprisingly joyful and welcoming. They are very optimistic, proud of the democracy they’ve become and eager to vote in municipal and national elections. We saw many of them in line to register for the next election.

In the centuries before the British, several long-lasting empires controlled the area. At the National Museum in Banjul, we were enthralled to learn about them. The earliest was the 600 year reign by the renowned empire of Ghana, wealthy from its mineral resources, but eventually subdued by the Muslim Almoravids from the north around 1000AD. The Mali empire of the Mandinka then gained control of the land from the Atlantic Ocean to current Nigeria until the onset of the Europeans in the 1500s. These were remarkable kingdoms little known in the west.

The River

Nowadays, it can be difficult to be a country which is mostly a river and two separated stretches of land. The busy ferry at Banjul transports throngs of people throughout the day across the mouth of the Gambian River, but cannot keep up with all the traffic, especially the trucks trying to carry goods across. Waits can be long.

On our crossing, however, we enjoyed a delightful one-hour conversation with an ambitious young robed woman who noticed our camera. Her work as a commercial photographer in a mostly male profession was a challenge she relished.

Yet, back through that imperial past, tribes along the river built hundreds of burial sites, mini-Stonehenges of dark laterite stone. We visited the most magnificent of these Senegambian stone circles, though formally on Senegalese land. (Click here to read the post.)

Gambia’s narrow strip of land is quite fertile because of the river, though much of the farming remains small in scale. Here is the irrigation system for one farm, where potatoes and other crops grow on mounds surrounded by channels of water dug out with a lot of hard work.

We went on a splendid bird-watching safari with the most knowledgeable expert – and a comedian as well.

We thought we were heading to some remote reserve, but the best site he said was amid the small farms that sit on the border between the salt water and the fresh – making for a dizzying mix of birds. This is one old favorite: the roseate spoonbill.

Another elegant Gambian bird on the prowl during our birding safari: the little banded goshawk

Banjul

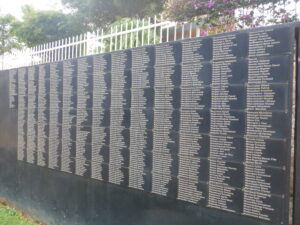

Arch 22 in the capital of Banjul is the dictator’s monument to his own triumph – along with other grandiose buildings. He betrayed those who joined with him to rule the country and then eliminated those who opposed him.

Now, the Gambians consider the arch and the museum inside a kind of testimony about that horrible time.

A view from atop Arch 22 over the capital city of Banjul. The old town is mostly a governmental center, with hulking white colonial buildings. However, many upscale resorts beckon along the coastline of endless beachfront.

The old British church in Banjul still offers Christian services on the main street.

On the streets of Banjul, the colorfully dressed women carry their big sacks, their wrapped babies, and often a tub of something on their heads.

The Gambia National Museum in Banjul, where we learned about early African empires, occupies another of the old colonial buildings from the time of British control. Vintage photos, artifacts, tools, and costumes from the past make for an interesting visit.

We were able to pluck these instruments at the National Museum, each of which comes from a different tribe of the area.

Another featured one was a xylophone of bamboo, invented by the Mandinkas, said to have magical power.

This charming mosque sits on the main street of Banjul near the large central field where celebrations take place.

You wouldn’t think that stuffed furniture would sell well outdoors in the very steamy conditions here, but that’s where you find them often together with carved wooden furniture.

We were taking a late afternoon walk on the shore at Banjul, where very few people dotted the vast beach. A group of 8 girls were posing for phone photos by jumping near the surf.

These two came over and we chatted for a while. They hoped to use the nearby hotel pool, but that was for hotel guests only. We told them that the ocean was much better anyway, though we’re not sure they believed it.

One day, we hoped, they would be welcome guests.

Serrekunda

Banjul is a small, somewhat sleepy capital. Inland from the coast, the suburb of Serrekunda has become the middle class center of the city. Restaurants, formal shops, a medina-style market make for lively and plentiful shopping options. And if you need a ride, a vintage Mercedes painted taxi-yellow can take you around.

Apparently this shop in Serrekunda offers not just best quality, but good prices as well.

In the Serrekunda market, a side street features medicine men like this. Their stands are piled with traditional herbs, oils, bark, leaves, and more – with remarkable medicinal value.

The Gambia is rich in fruit production. Serrekunda’s street-side stalls abound in whole fruit and cut fruit in whatever variety you want, and all grown organically.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from The Gambia, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)