In brief: A museum should offer a chance for discovery. Two “boutique” museums in Lisbon did just that for us, revealing the work of an artist and a poet.

Some museums cover vast ranges of subject matter; some explore deeply. In the span of a few weeks, we covered quite a range of notable Portuguese in Lisbon’s local museums. These included Raphael Bordalo Pinheiro, an artist with great commercial success, and Fernando Pessoa, an innovative writer who died too young. The museums among others were open to us for free on Sunday mornings just before we are locked down for the rest of the day due to covid virus restrictions.

Artist: Raphael Bordalo Pinheiro

How amazing to discover a genius in your own backyard! Well, in Campo Grande anyway, where we visited a museum devoted to Raphael Bordalo Pinheiro, a Portuguese artist and ceramics maker we never heard of.

Like Tiffany or Lalique with glass, we found, he fabricated ceramic pieces that brought artistry to everyday objects – a heritage of England’s Arts and Crafts Movement as well as the European Art Nouveau.

There was no better place to start than this incredibly elaborate, nearly meter-tall aroma dispenser that recalls Moorish style, with ceramic filigree and biblical scenes. It was a thank you gift to a benefactor that aided Bordalo Pinheiro during difficult financial circumstances – somewhat explaining allusions to scenes where Jesus is betrayed.

Or this gorgeous ceramic candelabra mixing dragons, mythical classical figures, a profusion of color – and a delicate array of leaves, flowers, and other elements from nature.

And he built on the centuries-old Portuguese craft of tile making, as well as endemic architectural style.

A clear reflection of Art Nouveau, this tile work weaves natural imagery into complex geometric design, here combining butterflies and wheat sprays in a deceptively abstract geometry.

The artist loved frogs, among many other animals he often included in his decorative pieces, tile scenes like this, or abstract patterns. As with Art Nouveau artists, nature was ever an inspiration.

He understood Portugal’s artistic contributions from the past, both in azulejos or ceramic tiles and the distinctive Manueline decorative tradition in architecture.

Here, for example, is a pedestal piece that pays tribute to that late Gothic 16th century style of Portugal’s Golden Age.

Another elaborate – all ceramic – piece nearly 2 meters tall. It features rich Manueline decoration and a complex collection of tributes to Portugal’s Golden Age, including sailing vessels, a cartouche of Camoes, shields, lions, and more.

It’s no wonder that the artist Pinheiro was given the honor of creating buildings in ceramic as Portugal’s displays at various international shows. The most notable was the Paris celebration of its Republic’s centennial where the Eiffel Tower was first displayed.

The museum gave a lot of attention to another side of his artistry, his deft and often dazzling ability in line drawings.

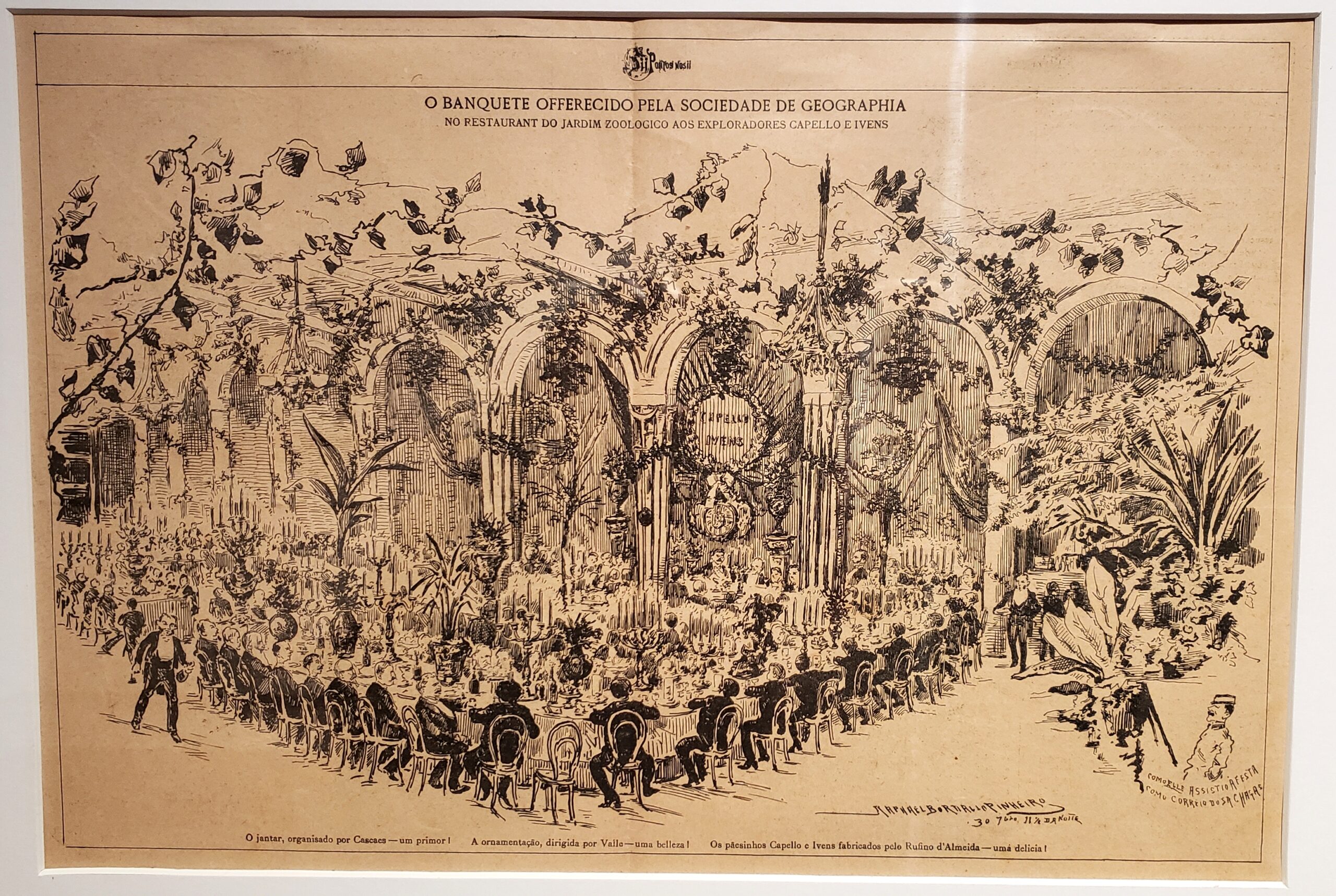

His architectural imagination is on display here, as he captures with great subtlety the elaborate building, the spritely decorations, and the individual characters at a feast celebrating two Portuguese explorers of Africa.

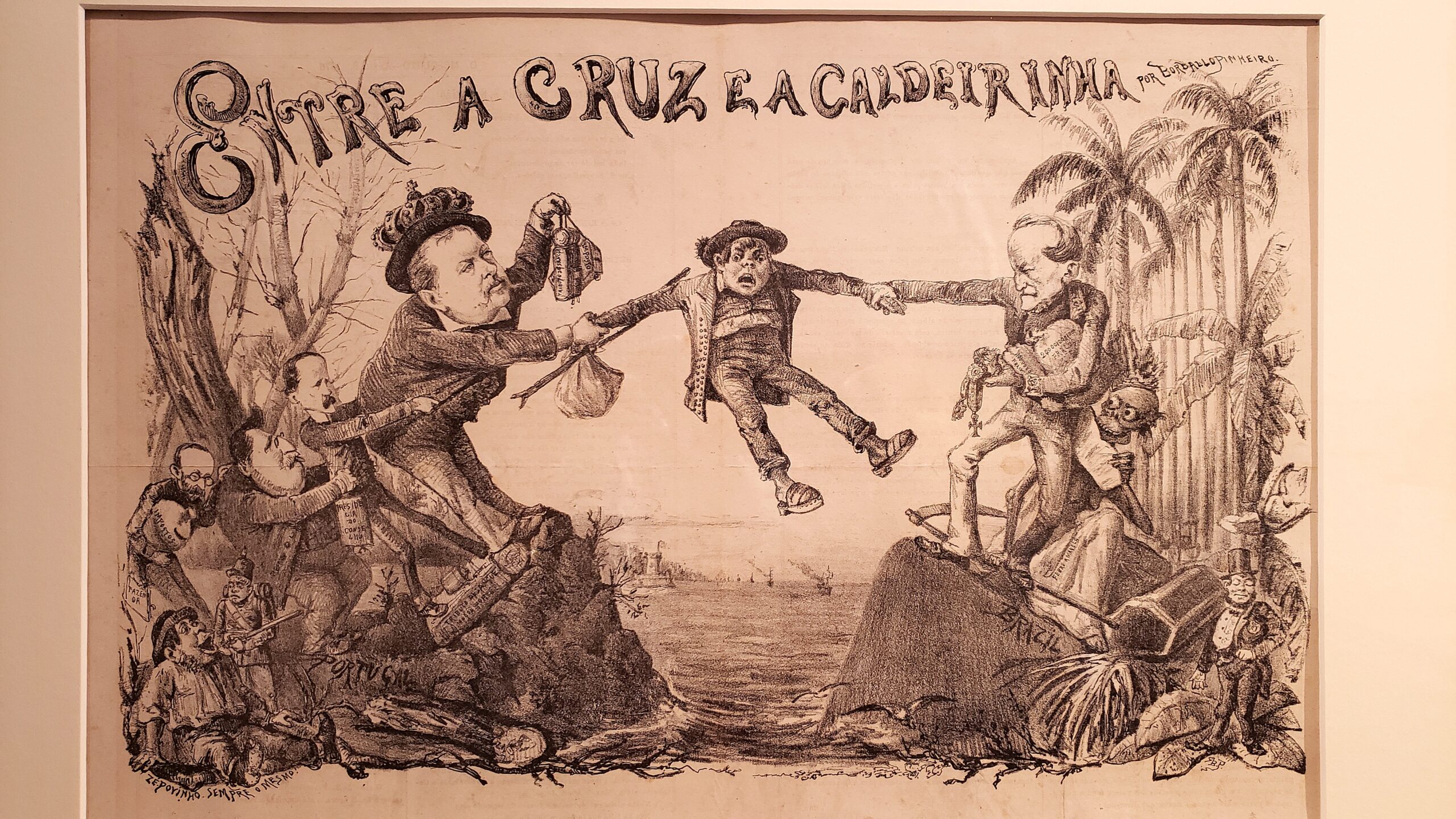

He often applied his drawing talent to satirical critiques of political leaders. In these elaborate published drawings, he used a Chaplinesque figure called Zé Povinho to represent a Portuguese people too often mistreated by those in power. We were thoroughly engaged by all Pinheiro’s skills.

Here he depicts the Portuguese common man – via the character Zé Povinho – pulled apart by rapacious behavior involving Portugal on the left and its colony Brazil on the right. Yellow fever, among other things, brings death onto the Brazil side. The Zé Povinho figure appears two more times here: impoverished on the bottom left in Portugal and stinking rich over in Brazil. Notice the allusion to the once glorious past of the country in the tiny Belem tower in the background.

In another illustrated commentary, a raucous party attending the new orçamento, or budget, is hauled by the straining figures of repeated Zé Povinhos. Pinheiro could draw with such a witty and lithe pen line that all his lithographs and drawings entertained us. Many of his drawings recalled Thomas Nast’s satires and Bosch’s fantastic gathering of figures.

Pinheiro often used food for a quick caricature of political figures, as in this parade with the backdrop of imperial buildings. Notice all the lowly turnips among the parading figures, and their use as soldier’s bodies in the military formation on the left.

We ended up delighted by the ceramics, but even more thoroughly impressed with his pen and ink polemics.

————-

The innovative writer: Fernando Pessoa

Casa Fernando Pessoa is an elegant and thoughtful tribute to a Portuguese writer known too little outside the country. Pessoa grew up in South Africa, first wrote essays and poetry in English, but became an early 20th century Portuguese literary modernist in Lisbon.

For the 15 years before he died in 1935 at the age of 47, he occupied a small bedroom in the building that now houses the museum. The rooms display many artifacts from his life, including identity cards, glasses, and even his mediocre school marks. Here we see him strolling about Lisbon like one of his own fictional characters.

“I know not what tomorrow will bring,” Pessoa wrote shortly before he became ill and died. He was telling about one day in 1914 when, in a burst of creativity, he wrote over 30 poems. It was “the triumphal day of my life,” he said. That enormous creative output is represented symbolically in the museum by this storm of hand-written sheets. Opposite is a similar room lined with blank pages, silently lamenting the work prevented by Pessoa’s early death. An inscription in that room repeats his quote about the future.

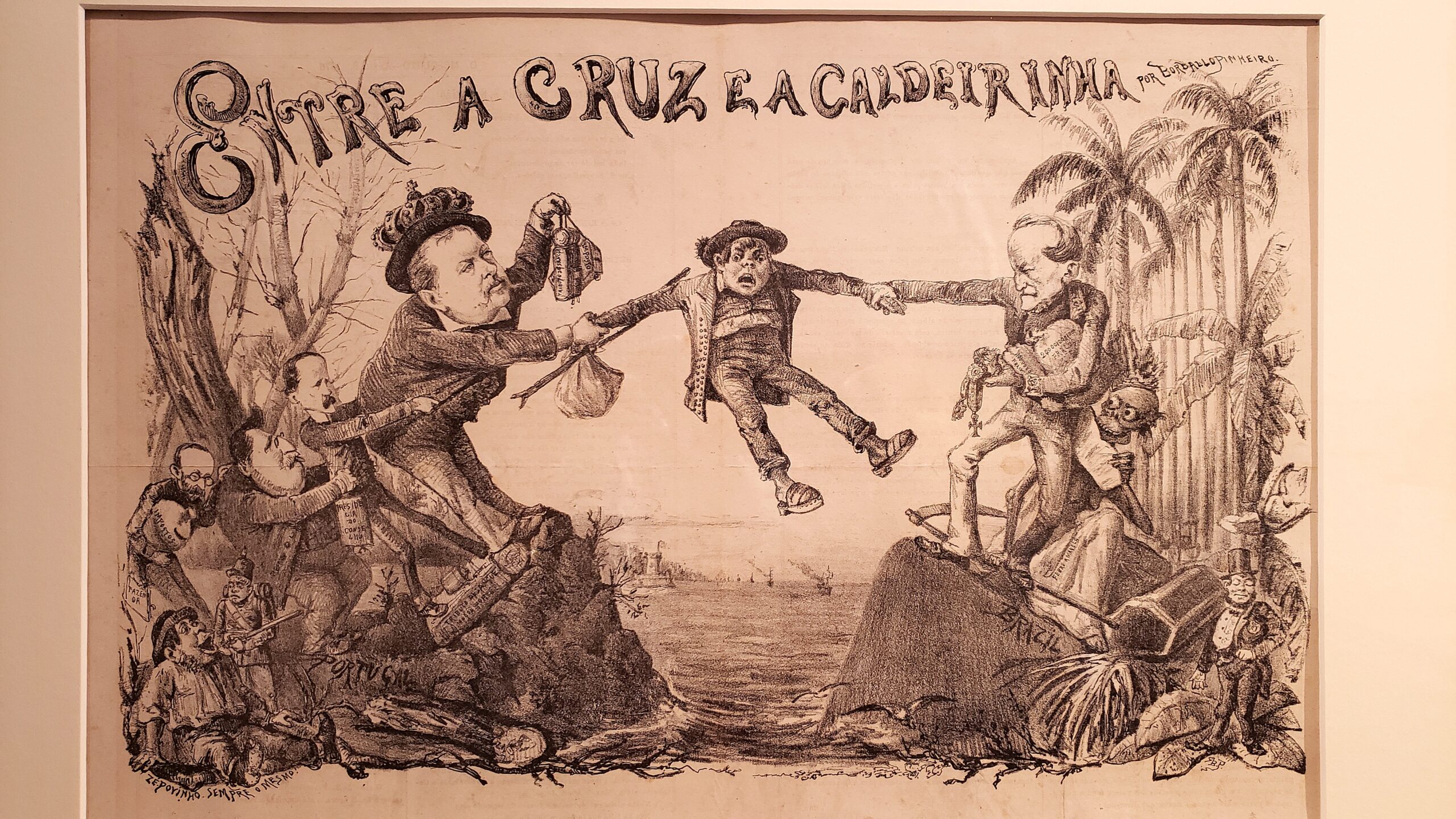

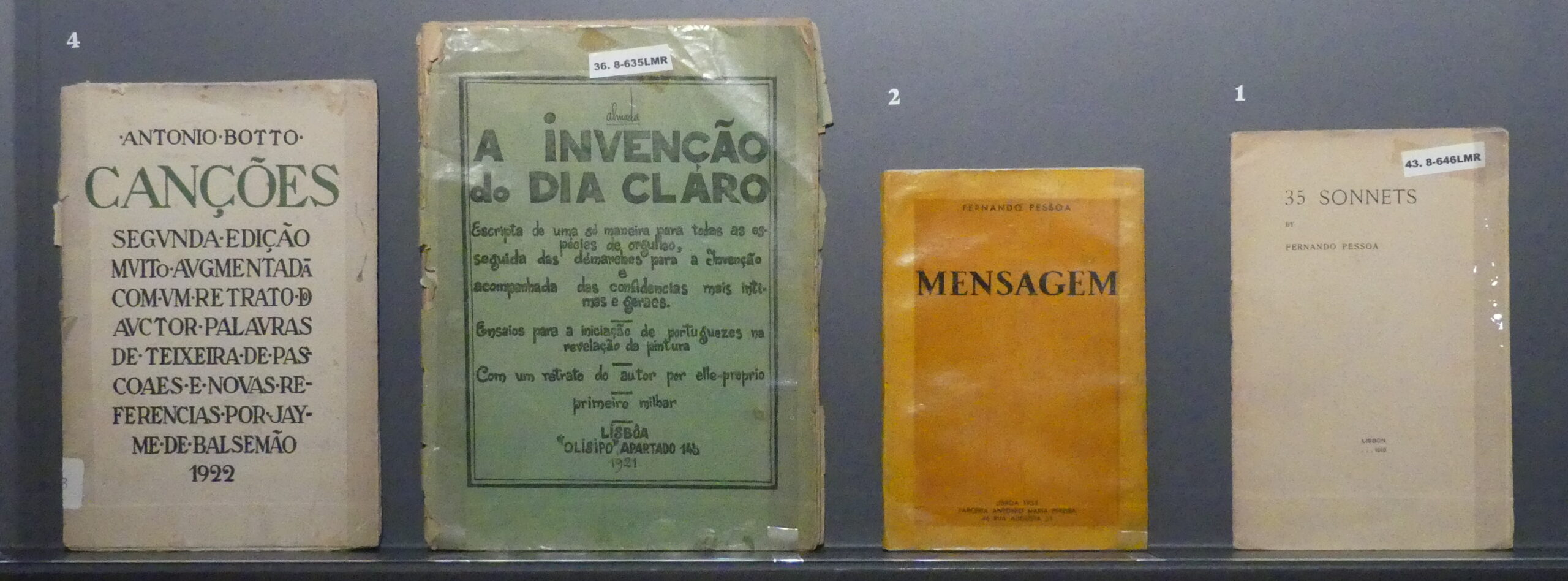

In Pessoa’s all too short life, he wrote extensively, edited an important literary journal, Orfeu (or Orpheus, an important modernist mythic figure), but published only a few books.

At the museum, most of his published work (from the 1910s thru 30s) has been put on display in original editions.

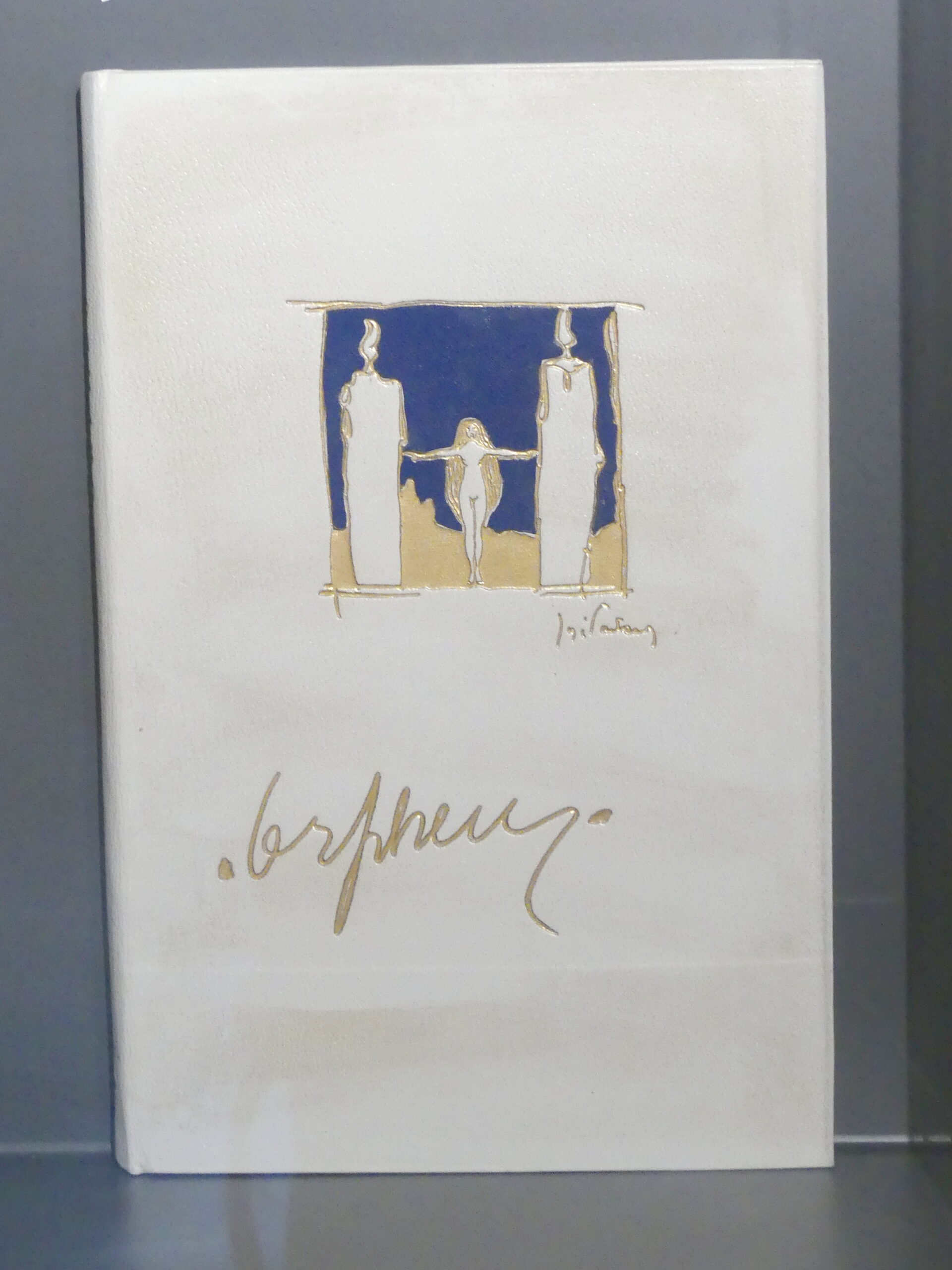

Perhaps the most important and interesting part of the collection consists of Pessoa’s sizable library, which has been lovingly re-created by the museum staff in a surprisingly engaging display of his eclectic interests – science, mysticism, poetry, phrenology, detective stories, history and more.

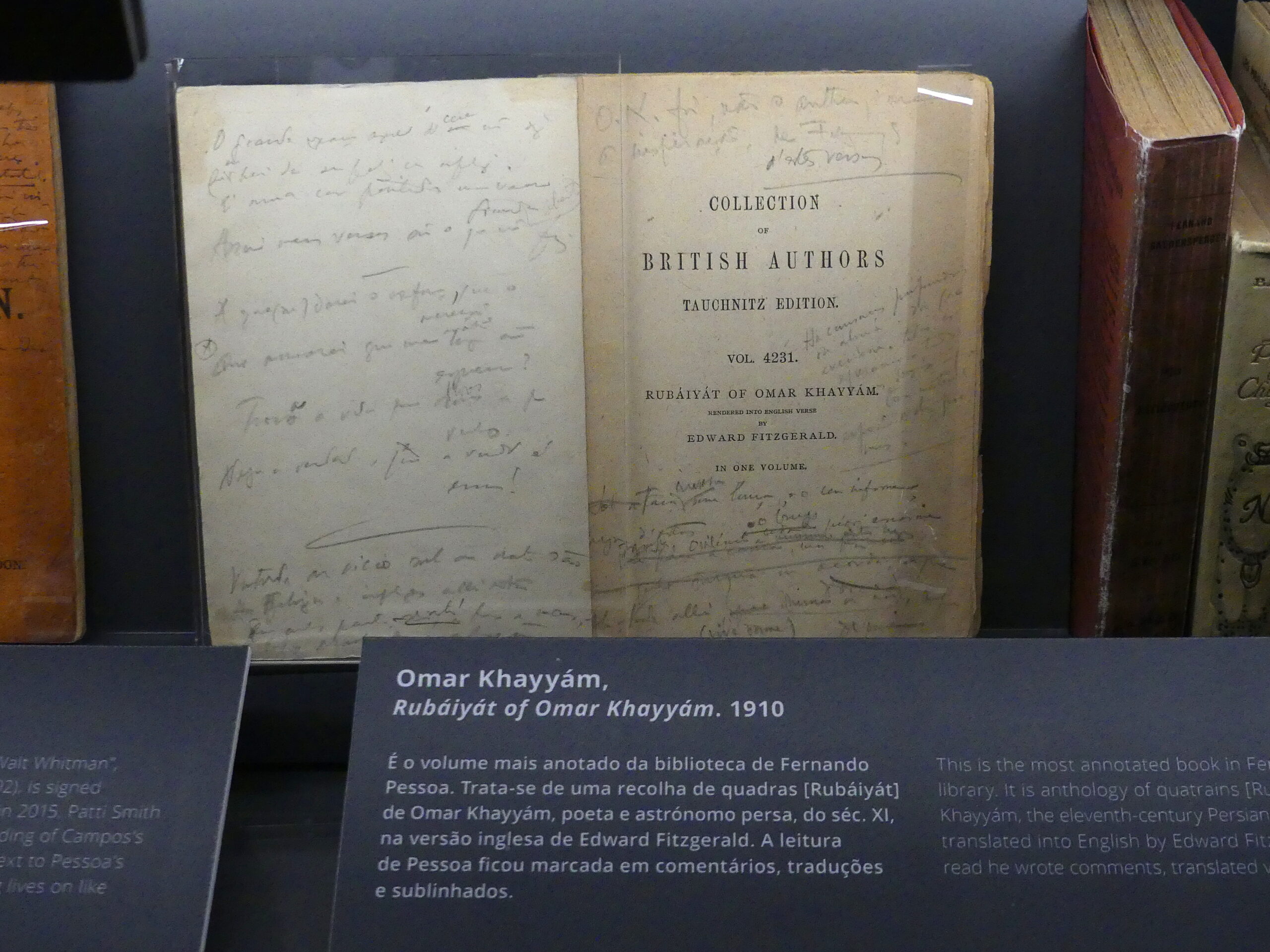

He annotated his books in great detail, as he not only read widely but thought fully about each of his books as he read them. Here is one example (the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam) of Pessoa’s rich annotations within the books of his library. These notes have also been extensively documented online at the museum’s website.

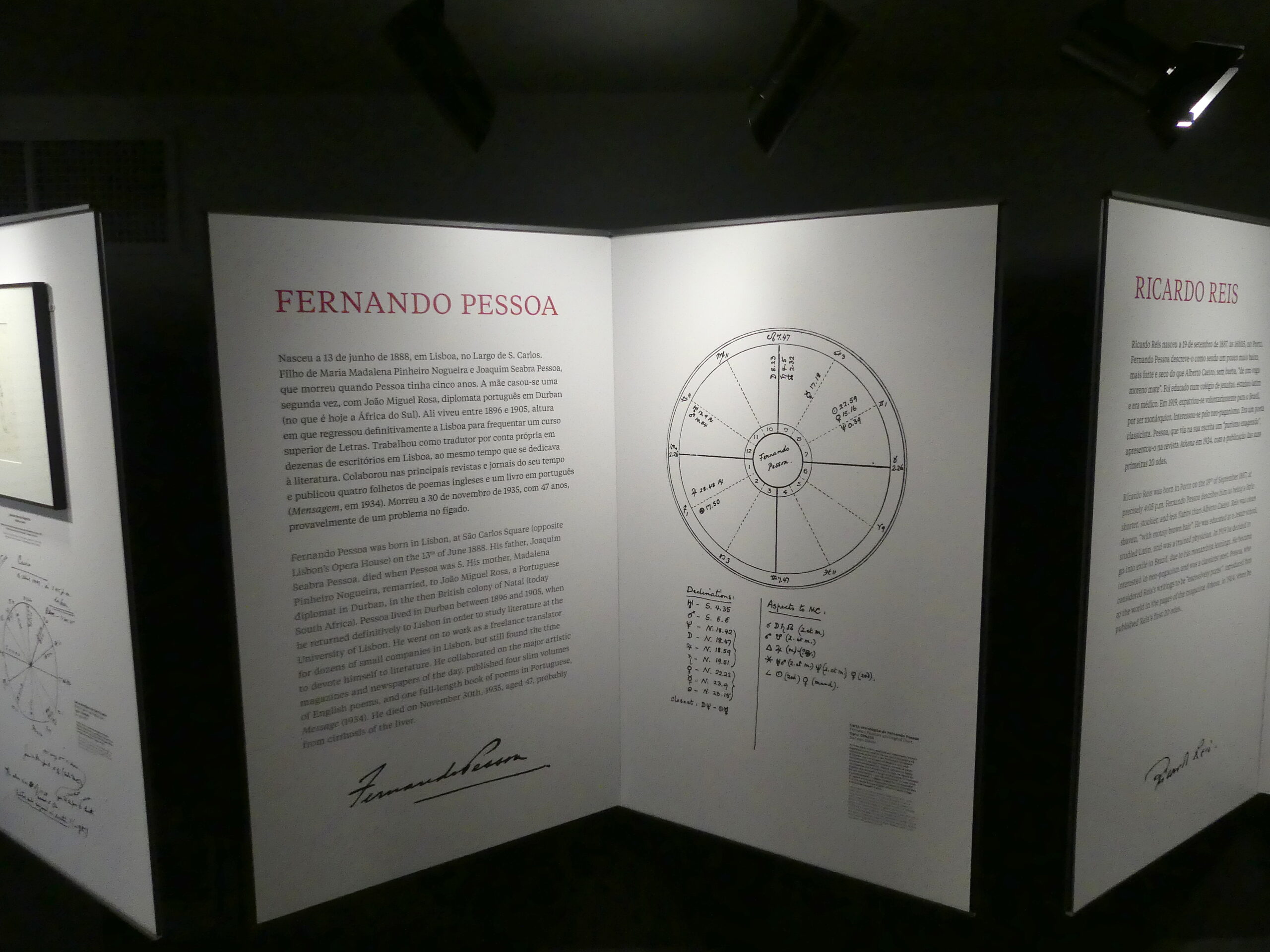

As the museum shows on its top floor, however, Pessoa left a treasure trove of fiction published only after his death. Much of it was published posthumously as his masterpiece, The Book of Disquiet (Livro do desassossego). In the book, we can follow fleshed-out “heteronyms” (characters developed with extensive biographies and even astrological charts) working and wandering in Pessoa’s home city of Lisbon. His imaginative realm of chameleonic characters and their city were as richly realized as Joyce’s Dublin.

Panels like these show the detail he invested in these characters and are complemented by audio excerpts from the book. As you see, one character uses Pessoa’s own name.

Discover them soon.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Portugal, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)