In brief: Yerevan museums underscore the richness of Armenian history, including quite a number of historical and art museums. Here are three of the best.

Armenians are rightly proud of their history, especially the 3000 years since they first took control of their land in the Caucasus. Early on the Urartu Empire ruled the region for 300 years. Later, the Armenians were the first to adopt Christianity as a state religion, then throughout the Middle Ages raised magnificent monastic churches for prayer and learning.

National History Museum

One day in Yerevan we discovered these ample reasons for pride in the rich collection of items from across the centuries now on display at the National History Museum in Yerevan.

Late in the 3rd millennium BC, over 4000 years ago, artisans of the region could produce stunning items like this, a silver goblet used in rituals with rows of finely etched hunters, warriors, and mythological figures.

An unusual clay hearth from the 3rd millennium BC. Nearly 5000 years ago, settlements were built here with domed clay houses, making them look a lot like Star Wars villages.

A collection of jewelry from the 2nd millennium BC, featuring an especially fine necklace of gold, agate, and carnelian. More bling like this was discovered in burial sites across the country.

About 1500 BC, carts like this transported the deceased elite to their burial mounds along with enough household and other goods to make themselves comfortable in the afterlife. This example came from around Lake Sevan, the largest freshwater lake in the Caucasus region.

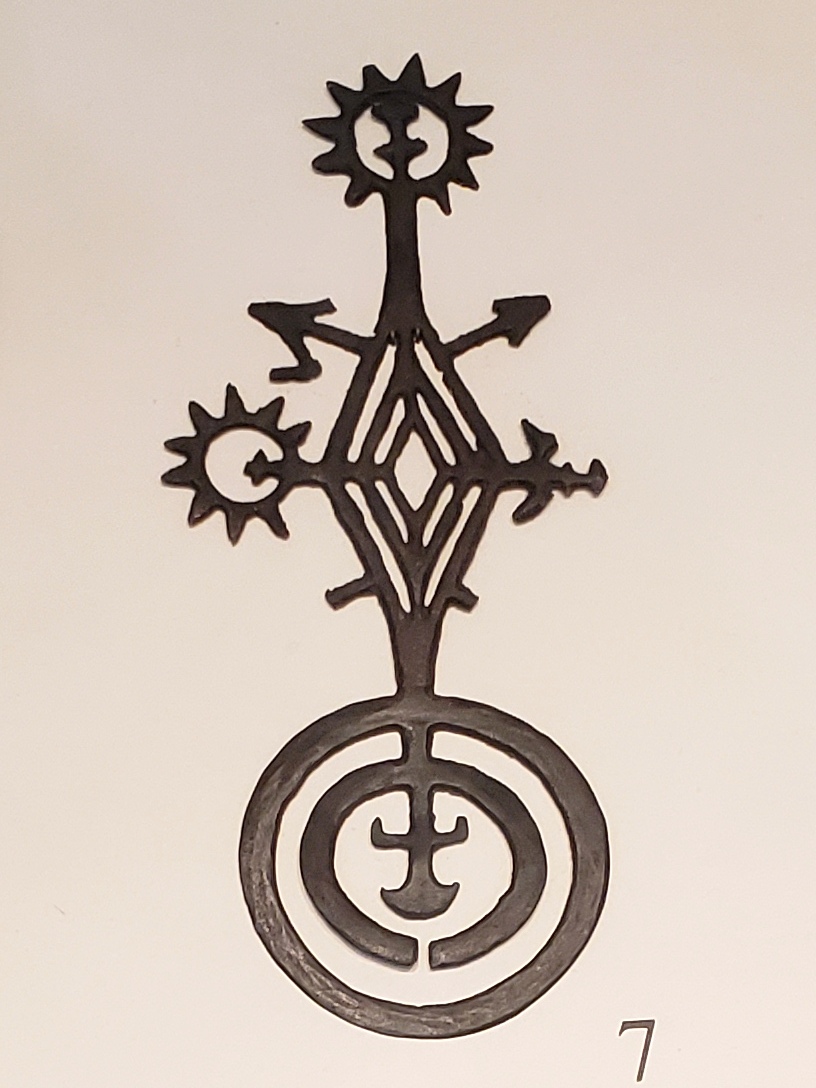

Even early on, about 1000 BC, learning and study were central to the culture. This bronze treasure is a model of the solar system, as the people understood it then. It’s now the symbol of the Museum.

Fine handiwork adorns this bronze belt worn for rituals, dating from around 1000 BC. Oddly symbolic animal figures suggest deer or more fantastical creatures within a decorative border.

At the origins of Armenian culture as we know it today, the Urartu Empire controlled the area from about 850 to 550 BC. Though it was difficult to photograph, this temple fresco on clay has survived to show the sophistication and artistry of that time.

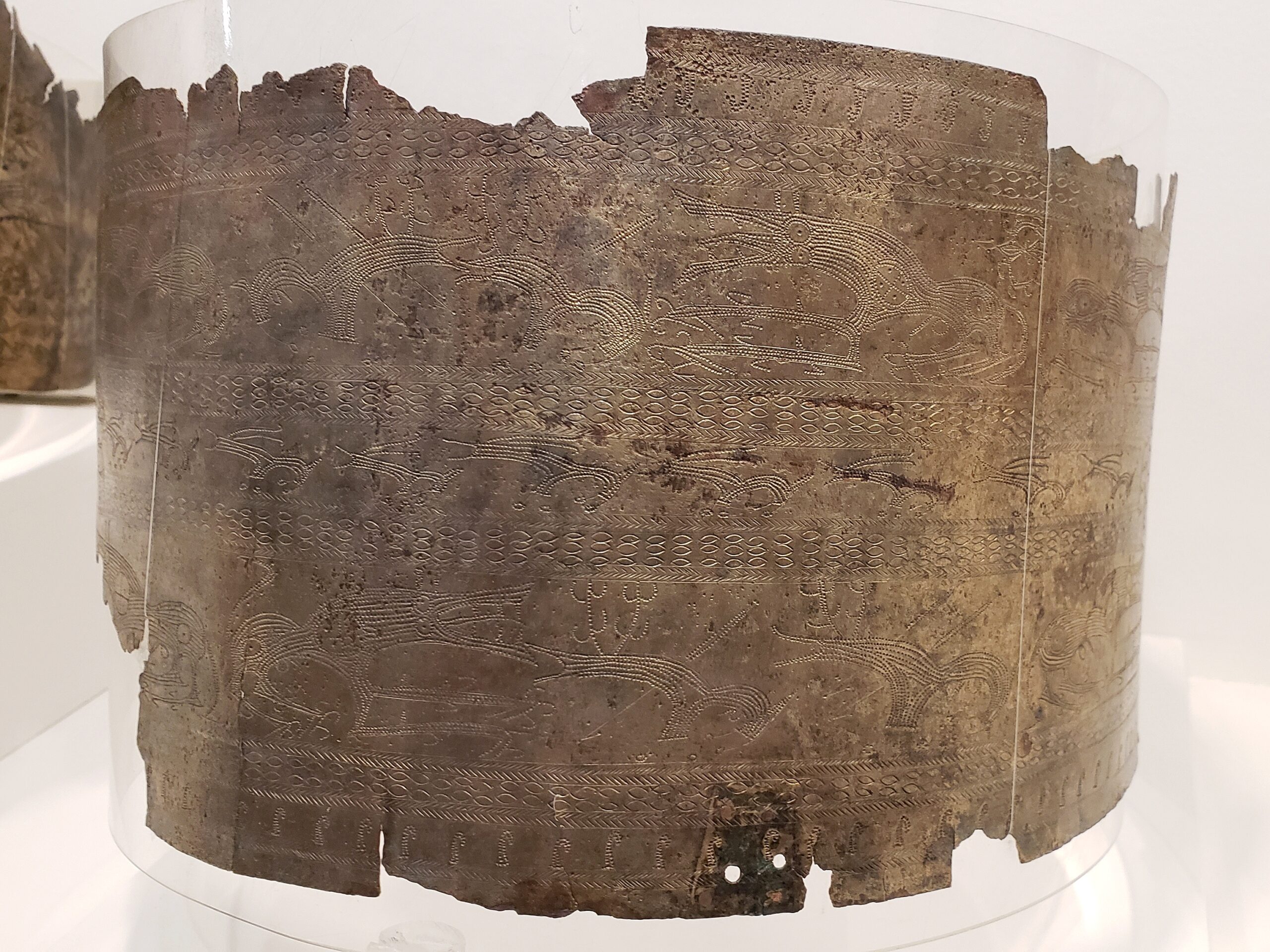

A bronze helmet from the Urartu Empire (850 to 550 BC) seems to show divine winged figures performing rituals under the threat of the four-headed snake. More war-like imagery, like the chariots and armed horsemen peeking around the left, fills the other side of the helmet.

Around the 6th and 7th century AD, some 300 years after Armenia adopted Christianity as the state religion, distinctive 4-sided stelae in tuff stone like this were commonly erected in church complexes. Each side precisely faced a compass point, with carvings of Mary, Jesus, or the saints dominating the east and west faces, and often more natural or symbolic imagery on the others.

Colorful and artistic clay ceramics of the 10th century from medieval monasteries.

The door from 1134 AD of the Arakelots Monastery in Mush, once in Western Armenia but now part of eastern Turkey. This stunning door somehow survived the destruction of the monastery during the 1915 genocide as well as various attempts to steal it away from the region. Through the late Middle Ages, from around the 10th to 13th centuries, Armenian leaders built or rebuilt monastic churches across the land, including western Armenia. These imposing stone buildings, many of which still stand in present-day Armenia, served as places of worship as well as centers for religious and philosophical study.

Precious doors and throne (1721) from the Cathedral of the Armenian Archbishop at Etchmiadzin, the Vatican City of the Armenian Church, about an hour’s drive west of Yerevan. To preserve and spread learning, medieval monks produced countless manuscripts at monasteries like this. Some of the earliest and still preserved illustrated manuscripts came from work at Etchmiadzin.

Other Yerevan museums underscore the richness of Armenia’s history, including quite a number of art museums.

On another single day we perused some things very old and some things quite new, no things we could borrow and one thing very blue. The old resided at the Matenadaran museum, one of the world’s largest repositories of antique manuscripts, notably illuminated medieval Armenian texts. The new occupied the Cascade, a kind of ziggurat with tiers of platforms that act like an 80-meter high fountain as well as a free display of contemporary art from the Cafesjian collection.

Over 1200 years of beauty and insight just a few steps from each other.

Matenadaran

For centuries, the manuscripts were kept safe in these repositories but now reside in the impressive Matenadaran Center of Yerevan, which picks up in the monastic centers of the Middle Ages, where the History Museum leaves off.

The interior of the Matenadaran echoes the entryways of those medieval Armenian monasteries from which the manuscripts have come, though the vivid medieval X-men fresco is quite untypical.

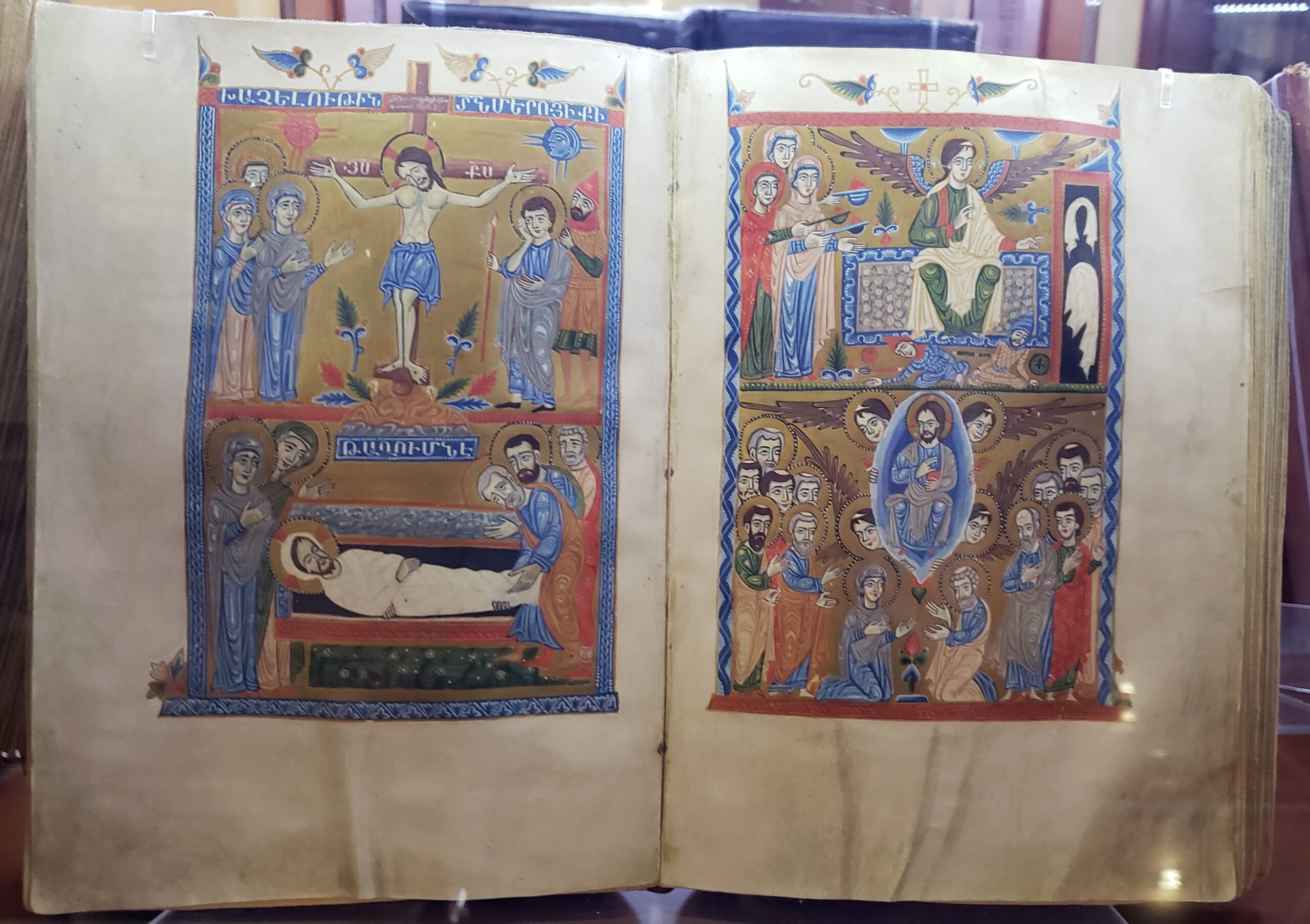

In a charming and also expressive style, this 13th century manuscript of the gospels from monasteries of the Cilicia region illustrates the last episodes of the life of Christ. The museum contains a huge display case of the materials used to make these colors, from plants to crystals to gold to sea snails (royal purple).

Copy of an ivory binding from the famous 13th century Etchmiadzin gospels recounts the life of Mary and baby Jesus in a remarkably fluid style. Note especially the nativity scene at the upper right with a very pensive Mary.

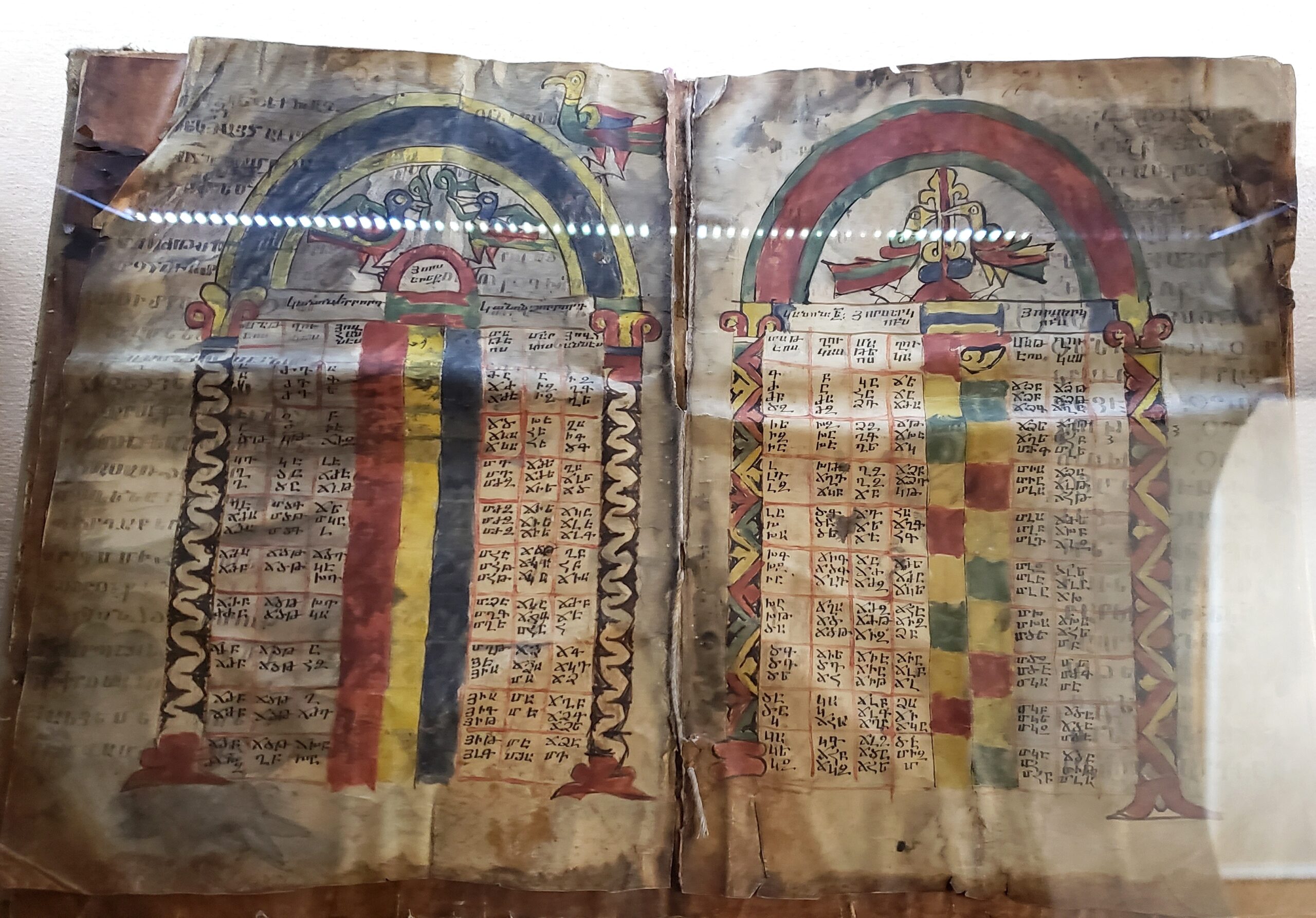

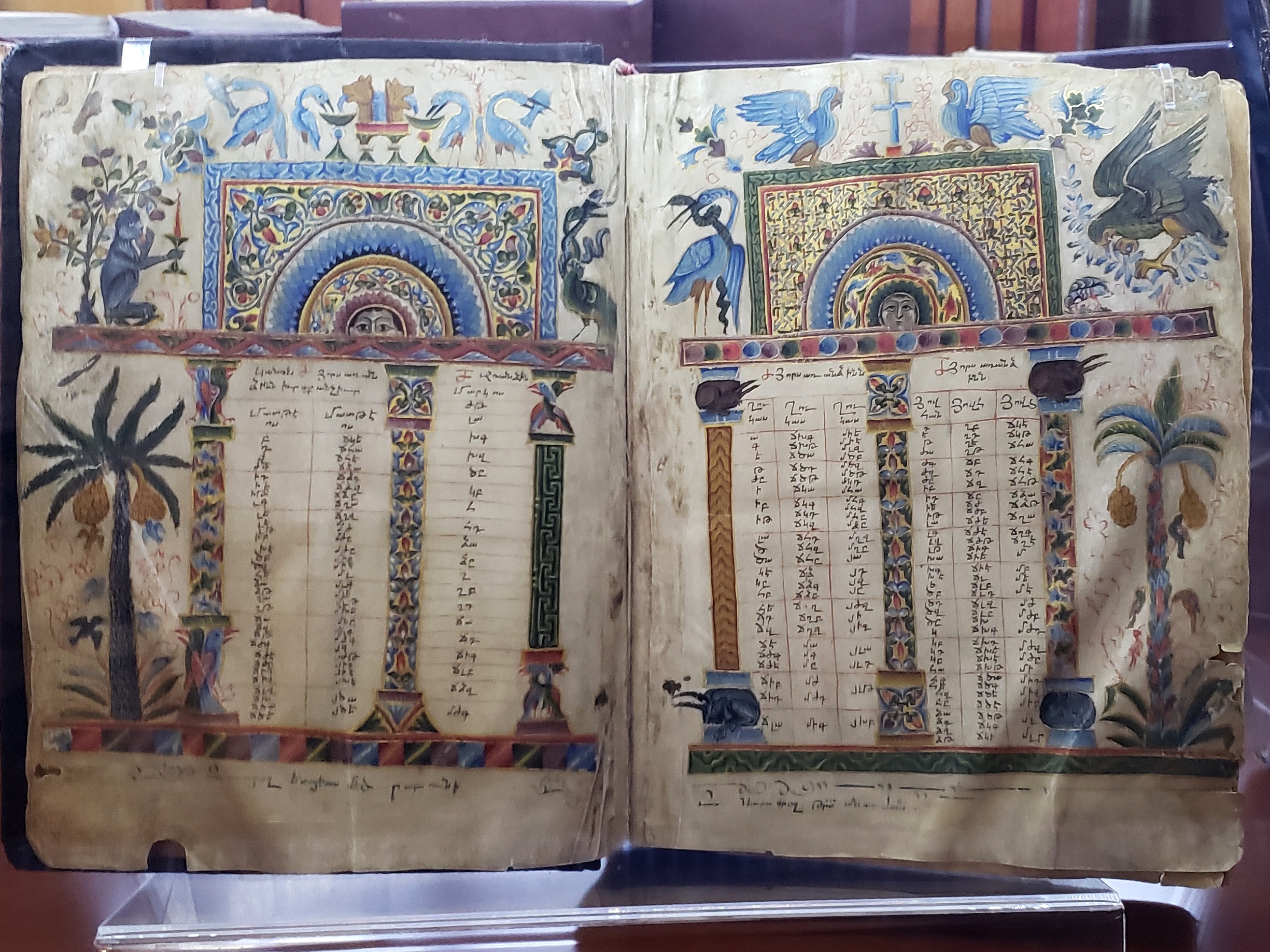

The earliest manuscript in the collection, the Sanasarian Gospels from 986, is open to an index page of recommended readings from the evangelists.

Another collection of the Gospels by noted Armenian artist Toros Taronatsi from 1323 delights in the natural world as well as the art of tiled walls and decorated columns.

The Cafesjan Collection at The Cascade

A view of the entire Cascade from the plaza below, with a priestly tribute to its designer Alexander Tamanyan, the urban planner from the 1920s and 30s of the circle that is central Yerevan. You can see behind him the four or five main tiers of the hillside structure accessible by stairs on both sides fringed with flowers.

The Cascade is both a fountain set on many tiers as well as a public space to display contemporary art works collected by Armenian-American publisher and collector Gerard Cafesjian.

This circular array of fountain spouts occupies the lowest tier of the Cascade. The motifs of circles and water are echoed repeatedly on other tiers, enhanced by traditional Armenian decoration.

A whimsical work in motion at a lower level of the Cascade.

On this level of the Cascade are more water-spouting circles, accompanied by a fan-like center and traditional Armenian decoration. A huge head (The Visitor by sculptor David Breuer-Weil) seems to be emerging from the pool with a fretful brow. The other visitor in the foreground remains undisturbed.

At this tier of the Cascade near its top, the sculptures in stainless steel by David Martin (and their central pool backed by more circles/hemispheres) continue the watery theme. Another figure is chasing a turtle along a nearby wall.

To the left of the Cascade, a set of interior escalators gives access to other art works from the collection also set on tiers like these Calder-influenced mobiles. Also inside, behind the open air displays, is space for special exhibits, which oddly are open on the weekend only.

Other artworks from the Cafesjian collection, like this ebullient blue kiwi by Peter Woytuk, adorn the open pedestrian plaza at the foot of the Cascade.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Armenia,

CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)