In brief: With the chance to visit different sorts of museums for free in Lisbon, we dove in to these three first.

A museum is not the first destination you think of during a wave of the virus pandemic. However, once we discovered that residents in Lisbon have free access to dozens of museum every Sunday, we started taking advantage of that opportunity.

And we discovered that fortunately most are lightly visited even though they were free and despite shortened hours due to weekend restrictions. That’s truly too bad for the locals and the museum, but nice and safe for us.

Here are the three visits we started with…

Gulbenkian Museum

Outside…The Museu Gulbenkian to the north of central Lisbon makes for a perfect visit during a pandemic because it offers a 16-acre (6.5 hectare) park surrounding its buildings.

Any of the public can enjoy it freely at any time. The founder of the art museum insisted on offering such an inviting place for all visitors.

The pathways we walked were sometimes sunny and sometimes shaded by diverse trees, dotted with flowers even in autumn and twittering with birds.

As we meandered, we discovered quiet bowers, grassy hillocks, and waterways teeming with ducks, fish and turtles. And we found two inviting cafes with outdoor seating, each offering typical Portuguese food and wine at low prices.

Inside…

We had visited the permanent collection at the Gulbenkian. We need to return to marvel at it again. This time, however, we toured two very different special exhibitions – gratis.

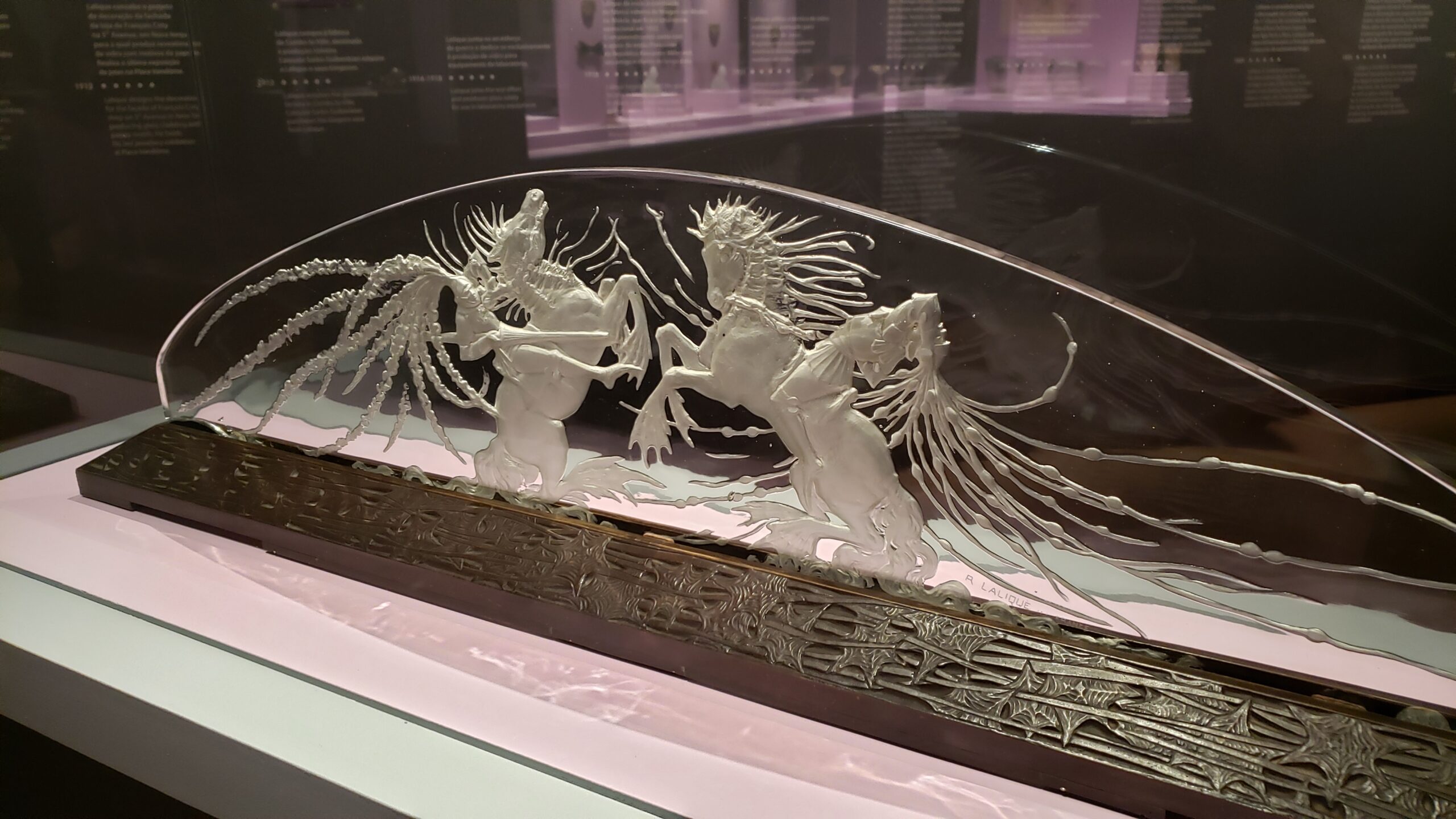

One was a fabulous display of beautiful pieces in glass (and metals) from René-Jules Lalique and his factory during the early 20th century. Gulbenkian knew Lalique personally and collected such pieces.

The other was a display of contemporary sculptural works created using casting techniques (generally by creating molds out of plaster). The international pieces were often exciting and usually edgy, but more mundanely we also learned about the surprisingly diverse uses of casting technology.

< Wall display of arms from plaster casts.

> Multi-faceted man by French artist.

< Regressive castings by an Austrian artist.

> A startling figure by a Scottish artist, a casting of herself as a kind of falling angel.

The outside of the museum has many charms, but the inside proved just as engaging.

Tile (Azulejos) Museum

Clay, fire, paint. Out of these three elements, the Portuguese have built an aesthetic and artistic tradition of azulejos, tile work.

Other than by strolling the country’s streets, Lisbon’s Museu do Azulejo offers the best chance to learn how the tile art evolved and see so many stunning examples like these we found.

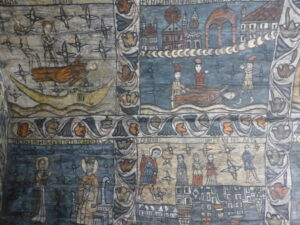

The Museum is housed in a former church and convent, which would be worth visiting on their own. The carved and gilded wood of the chapel is striking, especially as it is complemented by elongated, tiled scenes along its sides.

These stories from the lives of St. Francis and St. Clare are depicted in the azulejo style that became the most popular for story-telling by the baroque era, monochromatic blue on white.

Near the main chapel is an inner courtyard akin to a small cloister, with superb columnar caps and a splendid crown on the floor above it.

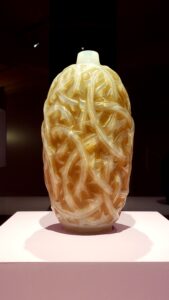

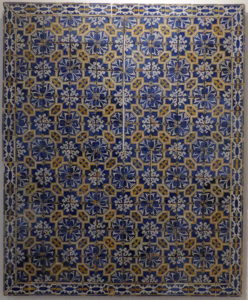

Nonetheless, the tile tradition in Portugal, as in Spain, began with the Moors who occupied the southern Iberian peninsula until the 16th century.

Their main style used decorative, geometric imagery on al zuleycha, or “small polished stone” in Arabic, as in this example from around 1600.

Several rooms of the Museum displayed many brilliant examples of these geometric patterned tiles.

From the Renaissance on, however, the Portuguese incorporated western motifs and figures.

As in other parts of Europe, first the church and then the aristocracy, with castle walls to adorn, put up the funds for the work.

An early 17th century display of emblems with moral lessons.

An altarpiece with a dazzling internal light includes an allegorical painting on tile about the Eucharist. Many works copied formal religious paintings; others, like this, used a more folksy style.

This mid-17th century polychrome tile array once decorated a wall along some stairs, and now is cleverly displayed at the museum.

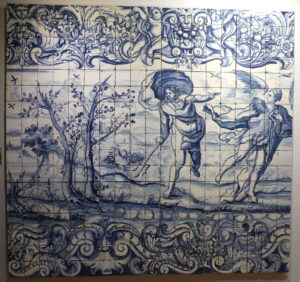

Art imitating art. An 18th century scene copied from a 16th century artwork drawn from Ovid’s Metamorphosis.

The museum includes a number of painted figures like this tiled soldier – a “welcoming figure” – who were set inside a formal doorway to greet arriving guests.

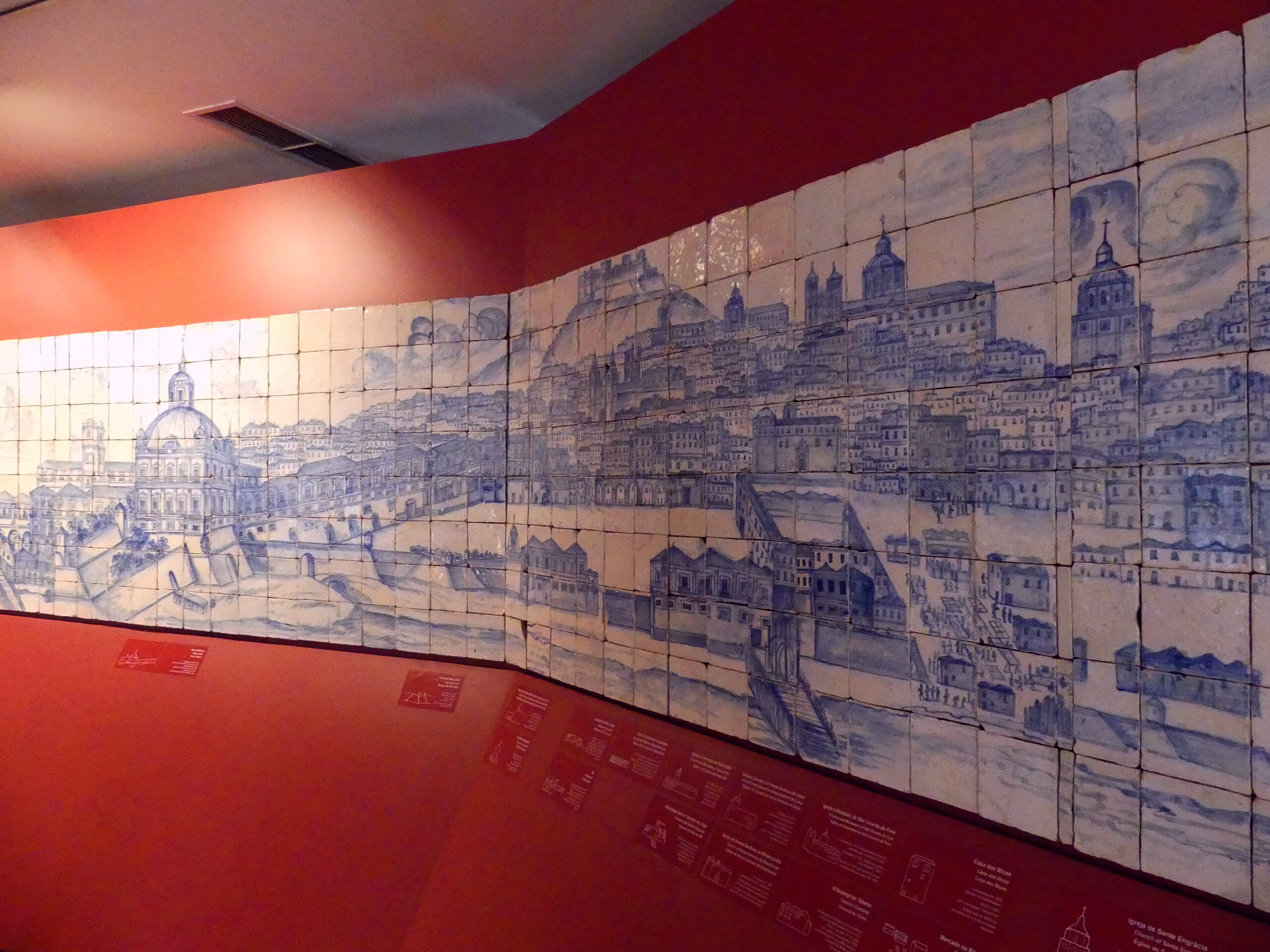

The wondrous conclusion for the museum appears on its top floor: a long tile panorama of Lisbon’s cityscape, in blue and white. It was done in the mid-18th century before a devastating earthquake transformed the city.

The complete panorama follows Lisbon’s shoreline for 20 kilometers or more.

This portion shows the heart of the city, with the vast Praça do Comercio in the foreground along with many churches and the medieval Castle of Saint George upon its hills.

As many visitors have discovered though, the modern day streets of Lisbon, Porto and other cities offer endless displays of tile – adorning buildings both inside and out, sacred and secular. The skilled tradition has turned the cityscapes into vital art museums as well.

Marionettes and their cousins

In the heart of Lisbon, we entered the fantasy world of Museu da Marioneta, delighting in its collection of marionettes, puppets, stick figures, masks and other hand-crafted dramatic “actors.”

The museum is housed in an imposing estate with a large inner courtyard, and entered by a grand staircase climbing to the upper floor.

A large selfie by some of the residents of the Museum, greeted us at the entrance.

Though mostly static at the museum, these figures have been given life by creative, dedicated human beings – around the globe and across the centuries. These figures have always entertained, taught lessons, or invoked the other world. When manipulated, the spirit of their creators enters them and we, as audience, accept their living energy.

We include here a variety of characters from our favorites at the museum.

Devils from another realm.

Masks used to narrate Sri Lankan stories about Buddha.

This other mask from Sri Lanka was used in healing rituals. The heads represent all the diseases to be prevented.

Hand puppets from Germany of devils and other evil characters.

We couldn’t help but be attracted to the malign figures, though most items in the European collection represent common folk or traditional figures like Punch or commedia dell’arte characters.

The museum has assembled a diverse collection of African figures, probably a very small sampling of the rich diversity of the “puppet” and “mask” traditions in all those countries.

This one seemed to be either hand-operated or worn as mask. It’s a swamp antelope, oddly with two women between the horns milling corn.

South America is also represented in the collection, particularly centering on uses of masks at Carnaval.

Here is a startling Colombian mask of a tiger in wood and feathers, used appropriately at Carnaval.

From Bolivia, came this appealing transformation of the head of a condor from its Carnaval.

The figure represents wisdom and wisely warns everyone of the forthcoming appearance of a devil in the ceremonies.

Portugal too has fostered a rich tradition of such craft, as we discovered while there. A museum employee even gave one family an impromptu show about tooth decay.

This Theatre of Master Gil by Portuguese puppeteer Julio de Sousa was fully populated by numerous hand puppets used to put on the original show.

By contrast, these meter-tall marionettes of São Lourenço – full figures in clay, wood and fabric – were manipulated by humans on a stage for a Portuguese performance of Don Quixote by Helena Vaz.

Each of these diverse museum experiences delighted us, especially since we might never have visited them if not encouraged by the free Sundays program.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Portugal, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)