Almoravid to Zianide via H & M

Much attention is given to the remarkable remains of Roman and Byzantine cities within Algeria. In visiting three locales around the country, we became just as enthralled by the ebb and flow of Islamic empires during the first half of the second millennium, before the Ottomans occupied the region in the 16th century. In these locations, we traced the rulers of North Africa (and parts of Europe) from A to Z (Almoravid to Zianide) in Tlemcen. And we were enlightened at two UNESCO World Heritage sites for H and M (the Hammadids at Beni-Hammad and the Mozabites of the M’zab Valley).

A to Z (Almoravid to Zianide) in Tlemcen: a half millennium of rule

Tlemcen is the second largest city of western Algeria after Oran. It has been, moreover, a very important seat of empire and religion. For three centuries before the Ottomans, Tlemcen was the capital city of the Zianide empire of northern Africa and a key trading center. The Zianide empire’s Citadel and palace still stand, now impressively restored. Before them, other Islamic rulers like the Almoravids strengthened the town. The city’s religious importance is evident from its numerous mosques in various Moorish imperial styles, from the Almoravid to the Zianide. We admired the still sturdy watchtowers of these old mosques, as well as the beauty of the more secluded 14th century mosque that evolved around the holy man, Sidi Boumediene.

Today’s Tlemcen

Steep bluffs overhang the old city of Tlemcen, providing striking views across the city.

City managers recently developed a broad plaza atop the bluffs, accessible by a cable car system that was just like those in ski country.

From the top, with some difficulty even with binoculars, we could yet identify the location of minarets and palaces we had visited during the day.

The quality of the photos from the cable car suffered from a common ailment in the sandy areas of Algeria, murky windows. We could barely see out of the windows on the train from Algiers to Oran and found the same problem on our ride here. We passed over some poor neighborhoods which locals warn one about. You can, however, in this photo detect the grand park at the start of the climb, closed currently for some reason, but originally a grand water basin developed by the Almohads in the 12th century.

Algerians are not just welcoming, but effusively so. We ran into these two men atop the bluffs overlooking Tlemcen. Inevitably, we started to talk…and were soon invited to share dinner, to be helped in several cities by their relatives, and be fast friends for life.

Yes, they don’t see a lot of tourists from outside Algeria, but hospitality to strangers is integral to the culture from Berber times on. (Sorry for the fuzzy photo; none of our cameras handled the low light very well.)

Down below, in the old marketplace or medina in Tlemcen, we called this man Habib Popeil for his ability to attract cooks with his slicing devices and his winning smile. We had seen similar displays in other Algerian markets, but this man was by far the best.

Our other market highlight was trying several street snacks from medina vendors. One, called Carentika, was a baguette with a yummy spread of chickpeas and oil inside.

A host of plane trees shade the main square of Tlemcen, named for Algeria’s first freedom fighter Emir Abdelkader. In the plaza, this boy seemed to be practicing how to drive in Algeria – whirling about rapidly and just skirting various pedestrians. He stopped suddenly before hitting us.

We were somewhat disappointed, but also grateful, to discover that a parent was guiding the vehicle remotely.

Old Tlemcen…

The Citadel of the Zianides

By the 13th century, the Citadel or El Mechouar, a fortified palace in the center of Tlemcen, became the residence of the Zianide rulers of the Maghreb for three centuries. Its imposing walls mask what had been a luxurious interior, one restored in recent times. This is the central courtyard around which countless rooms accommodated the leaders and their guests.

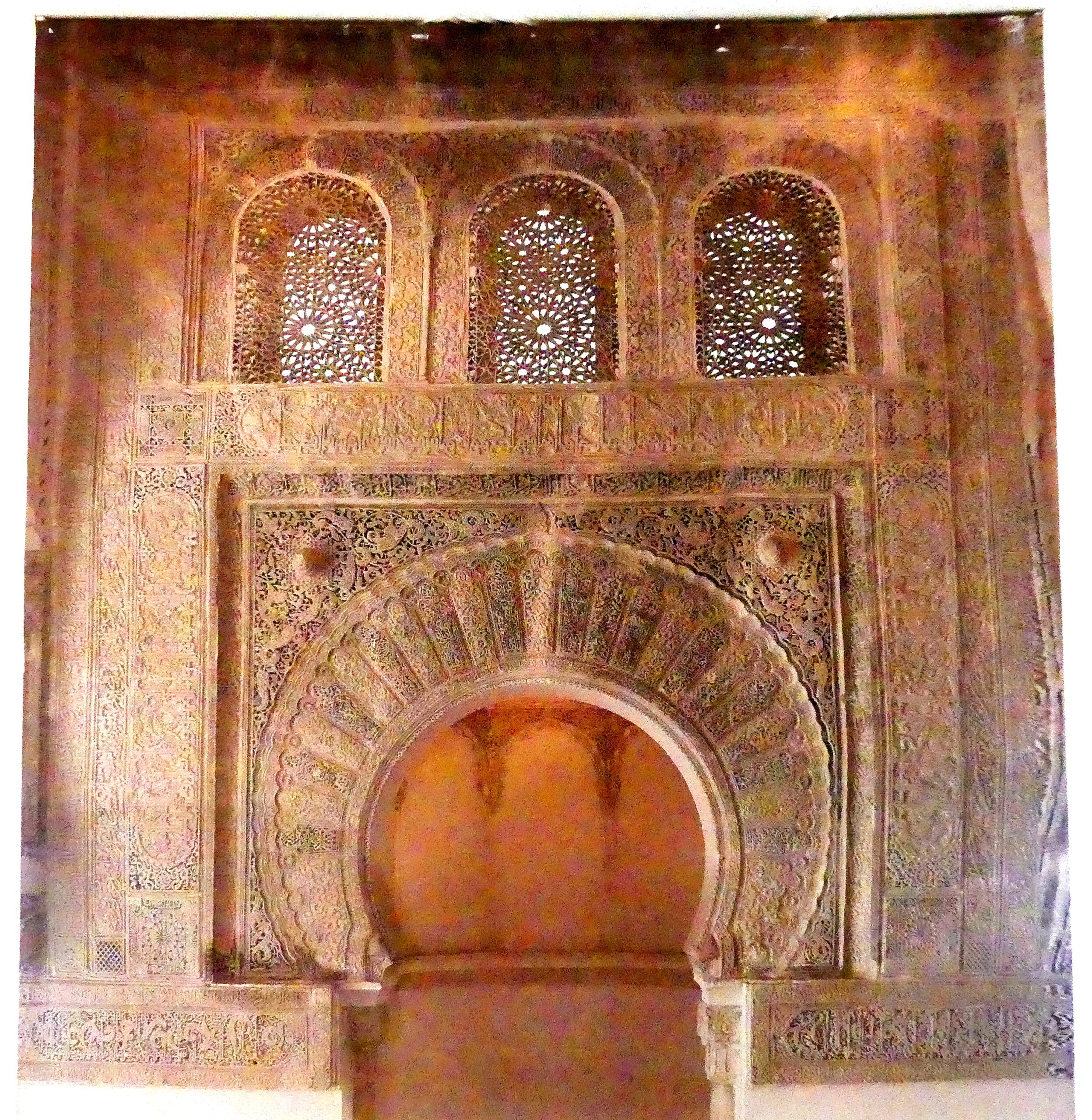

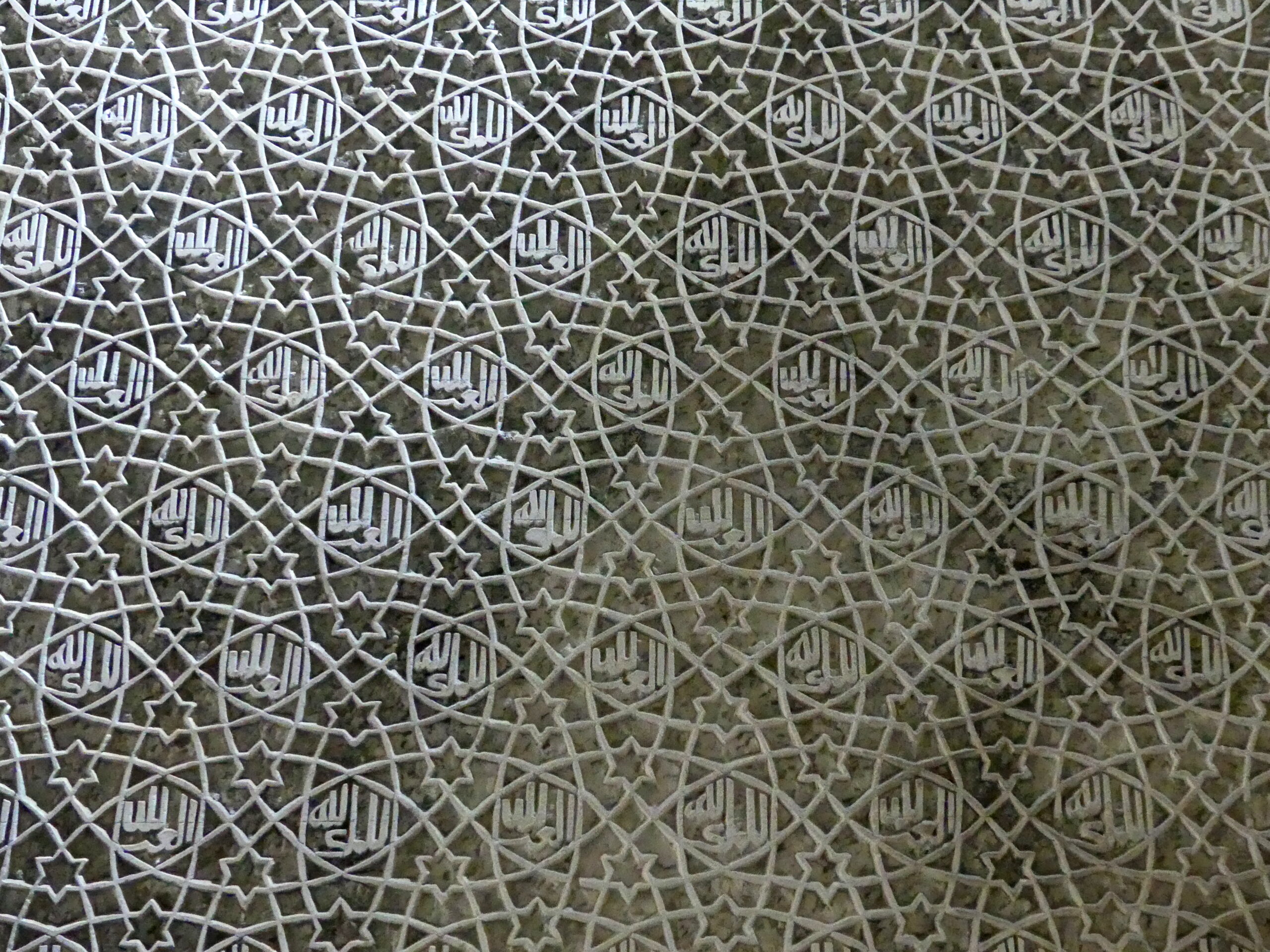

Restoration of the interior of the Citadel, the Zianide palace, has aimed to reproduce the old details of tilework and carving. We love the delicate, intricate decorative arts that grace Islamic building – this carved wall was mesmerizing. Overlapping circles define various other shapes, including tiny Seals of Solomon, with inscribed Koranic text throughout wishing us peace and welcome.

Mosques of Empires and Sages

On one side of the plaza with the young driver, sprawling discreetly over a huge area behind its simple façade, sits the most prestigious mosque, the Great Mosque of the Almoravids from the 11th century. We were not allowed to visit that one. But, on the other side of the plaza, a museum in Tlemcen’s former city hall displayed various treasures of the old mosques that have not survived, such as this charming wooden passageway at the museum from Al-Tansi.

The early 14th century Mansourah minaret rises 40 meters (over 130 feet) from atop a staircase, an imposing sight from the road. The back end of the minaret is open so you can see traces of the inner stairway as you stand in the vast walled area of what was the adjacent mosque. People look very tiny in that open space. Encircling walls below the bluffs of this plateau defined the Mansourah section of the city, which was eventually integrated into Tlemcen.

This 14th century minaret still stands as if new in the older part of the city called Agadir. The former prayer house and school are now just open spaces nearby. The brickwork decoration is still attractive, and also conveys meaning. The five arches at the top announce that the mosque is open both for regular days of prayer and special days as well.

The one mosque we could visit was part of a 14th century complex devoted to the holy man Sidi Boumediene, who followed the Sufi sect. We had waited an hour for prayers to conclude but still could enter the courtyard and open walled prayer area only due to the graciousness of its caretaker. While we waited, we wandered through other parts of the complex including parts of the madrasa school. There we admired the beauty of its domed interior.

We almost didn’t need to visit the mosque itself, given the splendor of the doorway.

While the interior of the Sidi Boumediene mosque may appear somewhat plain, it does feature elaborate etched decoration. And the carved stone adorning the outer doorways was equally engaging. The chair to the back right of the old mosque is where the imam sits to lead the prayers. The caretaker clearly enjoyed showing us the features, one of which was a wood pulpit that he would roll out of its storage bin during prayer. Our museum post from Algiers showed an even older pulpit like this.

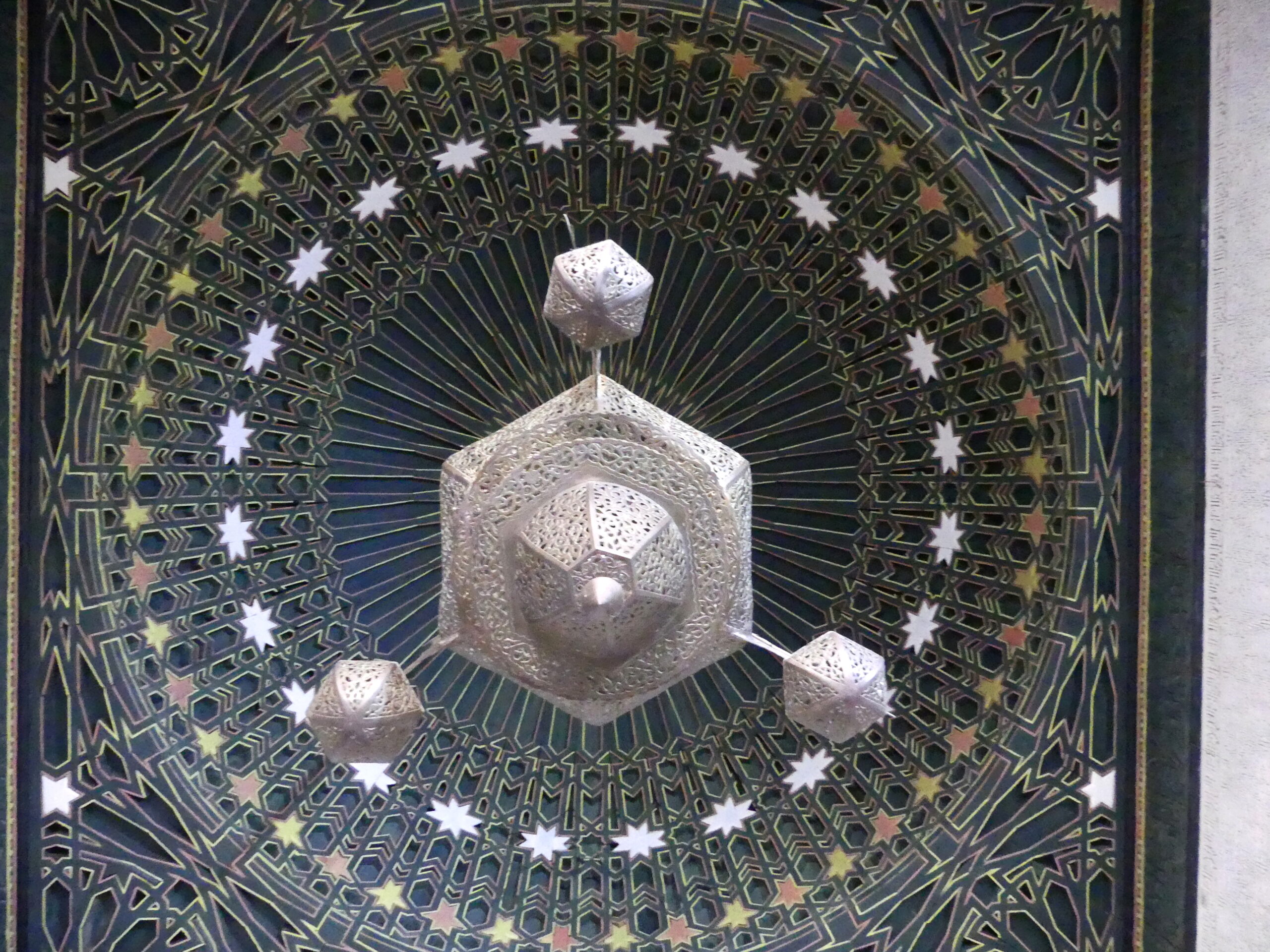

Our final visit was the burial place of the holy man, a vault adorned with this lovely tiled canopy.

H – Hammadid empire at Qai’a of Beni Hammad

You can drive or hike through the 11th century center of the Hammadid empire at the World Heritage site of Beni Hammad. All around you can marvel at the hilly landscape about 1500 meters above sea level, where violent geological forces pushed up subterranean layers into vertical striations.

Wealthy and powerful from caravan trade, the fortified city (qala’a) was also a nexus for artists and scientists. But invading Arabian forces forced Beni Hammad to be abandoned less than 100 years after its founding. Then the Almohads leveled it in the middle of the 12th century.

The palaces and walls are all but vanished, with the exception of a portion of one palace peering out over a deep canyon at the upper reach of the old city.

Otherwise, the lone marker of this seat of power is the stalwart and often imitated minaret that still overlooks the ageless landscape.

M – The Mozabite people of Ghardaia

Over 1000 years ago, the Mozabite people (of the Ibadi sect of Islam) began to settle in the fertile M’zab valley, a large oasis in the midst of the Algerian desert, and soon occupied five rocky hills surrounding that valley. Each hill turned into a walled city, a fortress (ksour) topped by a mosque and minaret that also acted as watchtower, looking out for danger and networking with the other towers.

In this overview of the M’zab Valley, the life-giving palm oasis spreads between the hilltop towns. The watchtower in the far center marks Ghardaia, the largest ksour (fortress town), which has sprawled into the valley as it grew, all but connecting each town. The hill to its left is another of the towns. We are standing at the high point of Bonoura with its tallest mosque just below and a fourth town beyond that.

In building the towns, the Mozabites knew what worked well for desert living. Emanating from the tower, constricted lanes wound in circles and radii down along the hill. Over these natural wind channels loomed thick clay block buildings affording plentiful shade for residents and heat absorption against the desert sun. In the buildings, cave-like apartments ensured privacy, with doorways only accessible indirectly and never located opposite others on a street . Wells distributed and preserved water for the community.

Not only was the physical layout of the cities distinctive, but so was their social structure. Committees of the mosques – including women’s committees – managed the religious, social, and administrative needs of the town, as they still do today.

For their preserved antiquity, the valley and its five towns, the Pentapolis, have been named a World Heritage site. During our visit, we felt transported to another time.

Pentapolis

Ghardaia, the largest of the towns, still looks ancient in its original central section upon the hillside. This narrow lane, climbing by steps to the central mosque and minaret, is quite typical of all the towns.

Over these natural wind channels loomed thick clay block buildings affording plentiful shade for residents and heat absorption against the desert sun. Privacy was ensured by the small windows, by doors that did not face each other on the street, and with L-shaped access to cave-like apartments.

Notice the texture of the wall on the right, which is roughened by palm leaves as the wall is made. That method disperses the sunlight despite the crowded lanes and breaks up rainfall to avoid torrents.

At its base, Bonoura’s peripheral buildings and original walls present a formidable facade built right on a natural rocky outcrop. Of all the five towns, this one shows from afar most like a fort, topped by its tapered minaret and lookout tower. Here you can most easily see the uniform clay construction that forms the tightly packed buildings, mounting in circles all the way to the top. The green at the base is the wide channel to handle the flood waters during rain and connects to the palm oasis.

Beni-Isguen is one of the smaller ksours of the Pentapolis. We are high atop the old principal watchtower, whose shadow was lengthening at the end of the day. The dry hills in the distance remind us that we’re in a desert. Within the encircling walls near us, you can perhaps detect the circular lanes radiating from the top. As is typical, the town is tightly packed with clay buildings – some unpainted and some brightly tinted when viewed from above. Most of the tapered minarets of the five towns are just as crowded by other buildings, so the broad plaza below us is unusual.

El Atteuf is the oldest of the five towns, a steep climb or descent through the labyrinth of streets shaded from the desert sun by tall buildings, which are most visible from this hillside cemetery at the edge of town. At the bottom right is an old mausoleum that is said to have guided the work of the famous architect Le Corbusier, along with the cave-like building style of the towns. Learning from the molded clay, natural shapes, and adaptation to desert conditions apparently altered his methods.

The Ancient Lifestyle – today

Both the men and women traditionally swath their bodies and their heads in white robes like these. After marriage, however, the women wrap their faces as well, with the exception of a space for one eye to keep watch on where they’re going.

As always, in the desert, water is the main concern. Wells throughout the towns of M’zab could collect rainwater when it came and give access to the oasis water otherwise. As people drew water from a well in any of the towns, spillage would flow to the adjacent space where one or more date palm trees always grew – thereby providing extra shade and nourishing dates. No water is wasted. This is one of the larger wells we saw in the five towns, appropriately at the center of Ghardaia, though the plaza had been enlarged in more recent times.

In each of the hilltop towns, markets like this bustled at the foot of the hills, level places for trade and exchange that left the main hillside town above secure and quiet. Only people on foot and donkeys would carry items up the winding streets, as they still do (with the addition of motorcycles now). The central market plaza, to which lanes like this entered, was also the site for meetings by village leaders in a stone semi-circle. There, in a public forum, they might adjudicate matters or make important decisions for the town.

What appears to be just some rocky rubble marked by white huts is actually a traditional cemetery for the desert Mozabites, where the shards mark the places of burial and the huts are sites for sacrificial gifts.

Within the hilltop towns, we saw many schoolchildren, boys and girls, in school or heading home afterwards. And we were pleased that all of them seemed quite joyful. This impromptu photo in Ghardaia captured the delight of two schoolgirls matched by the brilliance of their uniforms.

This restaurant was part of a large truck stop, whose various services supported long-haul truckers on the desert road connecting to the M’zab Valley. The staff was a bit perplexed as we quizzed them on the food they were offering, large vats with perhaps a dozen or more options. Yet clearly they were thrilled to meet some foreigners willing to dive in. Generally across Algeria, we found it easy to locate vegetarian food. A typical restaurant would offer a set of prepared dishes buffet-style without meat, or some local specialties like lubiyah (white bean stew). Separately it would display various meats and skewers ready to be cooked on a cylindrical grill out front. A bucket of baguettes always accompanies the meal, which typically cost under 5 dollars for two. The soup that Barry is pretending to scoop was vegetarian.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Algeria, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)