We were hesitant about visiting Ukraine in the fall of 2015. Wasn’t there a war going on? Why would Czech car rental shops not cover travel there? How might we find our way around its notoriously poor roads?

Except for the war part, we were accustomed to improvising around these problems, as in Bangladesh. And our son was insistent on going to visit the homeland of our ancestors from a century ago. So we committed…and found that Ukraine confounded these negatives in so many ways.

Our experience was split between the urban – cosmopolitan Lviv and gritty Odessa – and the extremely rural – the farmlands and villages of the Khmelnytskyi region about a 400 kilometer drive east of the Polish border, the region from which our ancestors emigrated. (Click here to read about the challenge of finding traces of their lives.)

As for the rural part, we began our visit somewhat like refugees in reverse. Aside from the insurance issue in Ukraine, we had been advised to avoid crossing the border by car. Word was it could take a very long time – and perhaps be quite uncertain – due to inspections for smuggled goods.

So, based on an internet suggestion, we arranged to store our rental car at our overnight hotel in Przemysl, the last town in Poland. A taxi then dropped us at the border for a 25 Euro cost, and we crossed the border into Ukraine.

We trudged a mile or so through a barbed wire corridor, beside which lay empty fields and some industrial debris. At a kiosk about a half way in, the Polish border guard waved us through. We had nearly the same experience with the Ukrainian woman at her station nearby. No line and no delay. Her passport review took just a few minutes, and seemed pretty perfunctory, though our bearded son, Alex, got somewhat more scrutiny.

On the return walk across the border, our morning arrival meant we faced a slower line of about a dozen people. And the Polish authorities thought about inspecting our bags, but they quickly realized that the Americans were not likely to be smuggling.

As we could tell from the Polish drop-off, however, smugglers had some success at this game. A host of large women and weathered men did a robust business pushing cigarettes, whiskey and other goods brought over from the cheaper Ukraine side to the more expensive Polish side. Even our taxi driver was persuaded to buy some alcohol. Based on all that activity, we were not quite sure who got stopped coming over. Perhaps it depends on who you know.

At the Ukrainian end of the no-man’s zone, in the quiet border town of Shehyni, we were met by the guide and driver we had arranged through our helpful landlord in Lviv. Maxim, our guide, proved to be just the right person for us: a student of Jewish history in Eastern Europe, an expert in old cemeteries and gravestones, plus an ardent protector of that heritage.

Roman, our driver, had brought a serviceable Mercedes van, though the windows did not open and it had no AC, a combination that kept us hot while we bumped over dusty roads later on. In addition to his mastery of the unevenly paved or rutted roads we often traversed in the countryside, he was expert in which local foods to try and the best of local drink, as well as which of the area’s laden apple trees we should harvest for a tart, juicy snack.

Our other concerns about Ukraine quickly dissolved. While the back roads could be potholed and challenging, the main roads were surprisingly good, a lot better than we had been warned. It helped to be going only 60 to 80km per hour for the most part, just in case, so Roman still needed six hours to drive the 300 kilometers to our home base, Shepetivka.

There was not much of interest along the way. What with the sweep of wars across this region for centuries, you can find few historical treasures.

At Olesko, we climbed to a Polish castle from the 13th century still in good shape due to renovation over the centuries.

At Kremenets, on the return trip , we admired the large castle complex and several monuments, though the town is more notorious for the genocide of its Jewish community by the Nazis.

At Pochaiv nearby, we gazed from below at a hilltop filled with a sparkling white complex of monastic buildings and myriad Eastern Orthodox churches topped with golden domes. Non-believers are not allowed.

Shepetivka was one of the three villages we could trace to our family, within 50 kilometers of each other, and it’s the only sizable town around.

In other words, it offered a tourist hotel.

That hotel was located on the outskirts of town near a crossroads featuring several fuel stations and clubs, but otherwise adjacent to quiet residences.

The hotel was itself a curiosity, with an odd circular gateway section that comprised the reception and the dining area. Off that a wide corridor led to just a half-dozen comfortable rooms. The whole thing was painted an intense blue. A few other patrons stayed there during our visit, but the hotel was being shopped for sale. Times were not so good apparently.

As for the conflict with Russia, we had no problems either.

But first a little perspective on distances. Ukraine is shaped like a ragged rectangle, about 1200 kilometers long and 600 high, roughly the size of the US west of the Rockies. Lviv, the second city of Ukraine, is only about 80 kilometers from the Polish border on the west. Kiev, the capital, is about half way across at the northern edge of the country. Odessa, the principal city on the Black Sea, is straight south of Kiev.

All the fighting with Russia over disputed territory is in the far east of the country, the Crimea. As we were only headed about one-quarter of the way across the country to Shepetivka, and at most halfway across to Odessa, we went nowhere near any military action or even the contentious region.

Yet, we did see some signs of that remote conflict, such as off-duty militia solders frequenting one of those clubs near our Shepetivka motel, and uniformed regular soldiers on the streets and in the cafes of Lviv.

In Lviv, we also saw several displays vividly adorned with posters lauding the soldiers fighting for independence and mourning those who died for it.

In Odessa, which is a lot closer to the front, we saw many large semi-permanent outdoor tributes also honoring the mainly volunteer Ukrainian soldiers holding at bay the well-equipped Russians. In a striking case of ‘politics makes strange bedfellows’, a photograph of a Jewish Battalion patch can be seen in the same display as a neo-Nazi rune (on the official flag flown proudly by the large Azov Battalion).

We could also see evidence of economic hardship in the worn buildings and infrastructure of the cities – a consequence not only of the war since 2014, but also governmental mismanagement, corruption and strong-man politics that still suppress Ukraine even after Soviet control ended in 1989.

At the Odessa airport just outside of town, for example, a large modern departure terminal still sits unfinished, for over three years and counting. The 1960s terminal in use barely merits the term “International,” and on a recent Saturday only three flights were scheduled for the entire day.

Yet there were positive signs. As a Belgian DJ told us, while waiting for his flight at that Odessa airport, the city is an inexpensive and lively secret that could easily become a hot new European weekend destination.

Even in the countryside, churches seemed to be enjoying a refreshing of faith and new coats of paint.

On a Sunday, we even passed a large new one to the east of Lviv, just completed but already filled to overflowing that day – hundreds prayed outside.

Lviv was the most hopeful and the biggest surprise, with bustling shops and lively cafes in its center. A light, joyous atmosphere seemed to pervade the town. The grand 19th century buildings and splendid baroque churches of the charming European central city looked a bit like Budapest or Vienna.

After all, till the late 18th century Lvov, as it was known, was part of Poland (the Lviv Art Gallery was filled with paintings by Polish artists). Then, till World War 1, it remained within the Austro-Hungarian empire, which added extensive building and infrastructure.

In almost any direction, you could savor stunning walks around town, though outside the periphery a Soviet drabness could settle in.

You could even move back in time along the old walls of the city and its medieval streets. Old wars hadn’t ruined it, nor had the latest ones undermined it, so unsurprisingly the central city had been named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

We were living on a short pedestrian street, just a block from the lovely boulevard park which was adjacent to the very grand, Austro-Hungarian opera house.

Lining the street on which we stayed were several posh cafes and a few art deco theatres.

In addition, the outer walls of several refurbished stores still displayed a list of their old offerings in German and Yiddish.

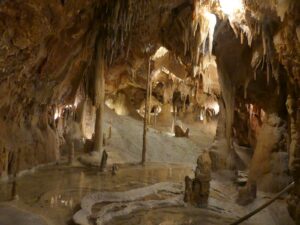

In our walks over four days, every corner seemed to offer a trendy bar like Pravda Beer Theatre, a craft brewery with a bandstand cantilevered on a glass floor above the entryway, or the lively cave-like bar beneath the opera house.

Not far from the center, a sleek new mall offered classy goods, while older buildings in the center had been refurbished to the same commercial purpose.

Off Ploshcha Square around the behemoth town hall, where the narrow trams clattered back and forth, we had our own outdoor favorite, the always busy White Diana, named for the statue of the goddess presiding over the space.

One walk, however, followed a more somber trail. We met up again with our guide Maxim for a look at the history of Jews here. The tolerant Austro-Hungarian empire had made Lviv and western Ukraine (known as Galicia) a place of opportunity.

By the end of the 19th century, however, millions of people, including a huge portion of the Jewish population, moved westward due to as Galicia’s economy faltered.

Those who remained – principally Polish Christians, Orthodox Ukrainians and Jews – faced persecution or wartime conflict, but somehow managed to live alongside each other.

By 1939, 340,000 people lived in Lviv, about a third of them Jews. We wandered along the boulevards and streets where the Jewish population lived, and saw the confines of the ghetto within which they were herded by 1941.

Later they were either deported to camps, or killed. Maxim filled in the sad details, as there was little trace of that time visible on the streets.

Instead, we visited a small, but emotional exhibition that Maxim had created to celebrate the Jewish culture in Lviv, and memorialize what happened. As a reminder of more tolerant days, he also showed us around the Museum of Religious History, where he worked.

With artifacts and other displays, the museum demonstrated the beliefs and iconography of all the religions practiced locally.

Our last stop was an open park near the former ghetto, behind the ornately bricked, neo-Moorish, old Jewish hospital.

Here Maxim had relocated hundreds of gravestone fragments he had rescued after they had been dumped by a crew that had cleared them from their original location. He had already arranged them in some rough order, but planned to create a proper memorial to the dead when he could.

Contemporary Lviv and Odessa are both ardent for independence and participation in Europe. As we saw, Lviv visually and culturally leans westward. Odessa, however, which had pretty much always been part of Russia, often leans eastward.

Everyone speaks Russian at the ubiquitous hip, smoky bars and the word to thank the bartender is always the Russian ‘Spasiba’. Visually, Odessa can even remind a visitor of a compact St. Petersburg, with stately, tree-lined boulevards in the central district, and aging, ornate baroque buildings along them.

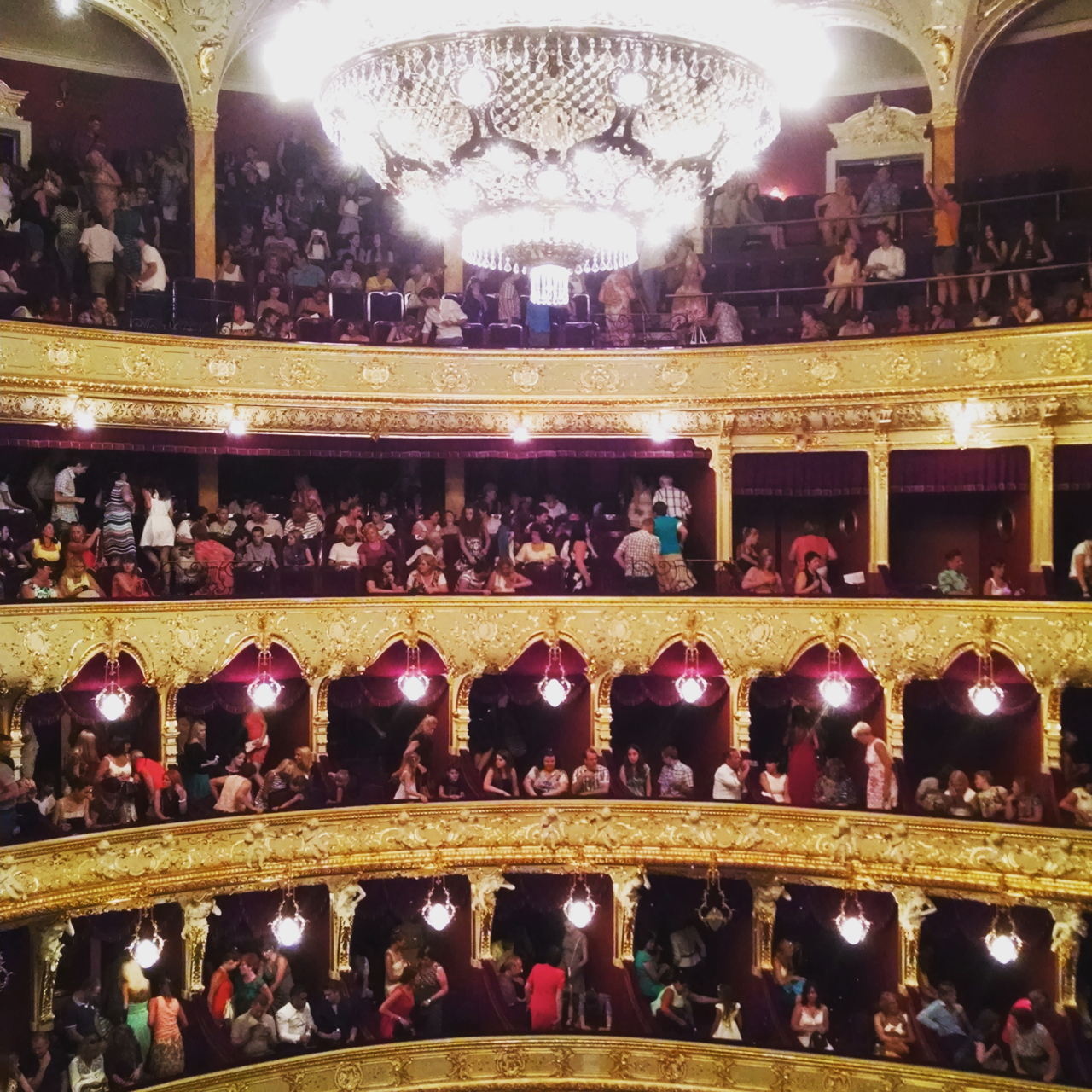

The gem of the city is unquestionably the recently renovated Opera House (1887), overlooking the giant Black Sea port. Though built under Russian rule, it’s more Italian Baroque in style; its plentiful marble and gold ornament can easily outshine the productions taking place inside. It surely belongs near the top of the list of the most beautiful buildings ever built, but it’s a bargain to visit: a matinee ticket to Carmen cost only $15.

The Opera House is perched at the top of the city’s famous Grand Staircase, designed nearly 200 years ago by a St. Petersburg architect. This set of several hundred elongated steps was built as a formal entrance to the city from the sea. Now it’s called the Potemkin Stairs, in honor of the famous scene of a Tsarist massacre within Eisenstein’s film, Battleship Potemkin – an event that never actually happened.

Unfortunately the European Union has not moved rapidly in supporting Ukraine’s embrace of the west. The economic lift from greater integration with the EU or productive investment has been slow to develop. With all the problems left over from its recession, the EU is even becoming more hesitant to commit. Now it’s also wrestling with the immigrant refugee crisis. In April 2016, the Dutch people, feeling negative about the EU and fearing more problems if Ukraine eventually became a full member, rejected a simple trade pact that would have helped Ukraine a lot.

Further progress will be slow. The EU’s inaction has encouraged troubles to march relentlessly down those Odessa steps, as it were, trampling on future lives.

(Also, for more pictures from Ukraine, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the Ukraine itinerary page. To see any photo enlarged, just click the image.)

BTW thanks for posting this!