The remarkable ruins of five ancient cities uncover over five hundred years of Roman occupation in northern Algeria.

Tipaza and Cherchell

Wealth and power flowed into northern Africa across the Mediterranean from 200 BC to 200 AD. Within 100 kilometers west of Algiers, two towns demonstrate the vitality of the Sea in that era: Cherchell (once Caesarea) and Tipaza (once Tipasa). As was typical, both were developed as miniature versions of Rome. The Vandals, Moorish tribes, and time itself destroyed most of the ancient structures, but together they offered enough tangible history for us to voyage thousands of years back.

If you squint a bit to block out the shiny new boats in the harbor, you can visualize the Punic (Carthaginian) trading ships or war vessels bobbing in the same space at Cherchell.

By contrast, this tranquil area was the old harbor of Tipaza. With its golden stone, this is now a beautiful seaside location for exploring and lounging. You can tell from here how much of the surrounding old town has become shrouded in trees.

Ancient Tipasa, a city of some 20,000 people, became a typical Roman colony sprawling over many hectares at the edge of the sea. Wandering the whole site can take hours. This is the main city street that terminates at the old harbor. Mount Chenoua in the distance separates Tipaza and Cherchell. Local lore says that it looks like a pregnant woman on her back. The people who live there speak a distinct Berber dialect.

On a weekend day, many parents brought their children to learn directly about their heritage. Or just enjoyed the setting for an outing.

This atmospheric site at the edge of the sea was a necropolis, with some open tombs evident at the far side of the ellipse and niches carved into the red rock surrounding it. In the past, as well as today, it was a place to meditate and pay homage to ancestors.

Clay storage vessels, embedded in the ground at a market stall at Tipaza, held grains for sale.

One of the best preserved pieces in Tipaza was this Nymphaea, or public fountain, ably captured by a passing tourist.

High upon a hillside near Tipaza sits this World Heritage Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania from the 1st century AD. It may be the burial site of the long-ruling king of Numidia, the renowned Juba II, and his wife, the daughter of Antony and Cleopatra.

Constructed of countless stacked blocks of stone, it contains several chambers inside, accessible by a corridor winding through it. These are closed off now, but in the future visitors will be able to walk inside, we were told. Though the domed surface has eroded, the lower section is still in good shape, with 60 carved ionic columns and four doors in the cardinal directions. Originally 40 meters high (130 feet), the mausoleum, even in its currently reduced size, makes the people look very small…as we also felt next to it.

Fishing and trade across the sea made these sites wealthy. So, it was no surprise to find a string of open air eateries along this boulevard, many of which were thronged by visitors and families enjoying Tipaza on a weekend.

The exterior of Casa Mia might have been a bit garish, and smoke from the grill on the right often billowed over the tables, but the food was excellent. We later found this cooking arrangement – a smoky grill outside a restaurant – all around Algeria, whether to prepare skewers of meat, cuts of liver or steak, or fish as here.

Djémila and Timgad

We were perhaps even more in awe of two Roman settlements farther south and about a 1000 meters (3000 feet) higher up in the Algerian mountains. The UNESCO World Heritage sites of Djémila (Roman Cuicul) and Timgad (Thamagudi) are two of the best preserved Roman towns anywhere. With populations that reached about 15,000, these mountain cities each occupied a grid pattern of roughly half a mile square (half to 1 kilometer) – and feel even bigger. As with the coastal towns, both aimed to replicate in miniature the look and feel of the mother city of Rome for her expatriates. So, they were designed with similar street layouts, temples, forums, baths, theatres, villas, and finally Christian churches.

These cities also demonstrate the importance of northern Africa to Rome after Carthage’s defeat. They defended the territory against the local Berber tribes. Plus the land’s fertility and access to trade across Africa ensured wealth that lasted for five centuries. The ruins left by invading Vandals and Arabic tribes survived under layers of dirt up to a meter high – now happily cleared to reveal the marvels.

In this splendid mountain setting near the confluence of two rivers, we could traverse five centuries of Djémila’s evolution: from the oldest part in the 1st century at the left (founded for ex-military families), through the uphill expansion around the 3rd century in the middle, and then through the Christian era of the 5th century at the right. The physical distance from bottom to top is about a kilometer. The walk through time was truly exhilarating.

It’s hard to tell given the scope of the photo, but the newer part at right is stuffed with the countless remains of houses and public buildings, including the later Basilica.

Here we approach the 3rd century section of Djémila, where Septimius Severus founded a new temple, arch, and forum to renovate the 1st century city, along with a residential section nestling beyond the temple.

A closer look at the well-preserved Severus temple and the grand space of its Forum from the 3rd century. Those tiny figures climbing the stairs show how big it is. People at that time gathered on the right side, near the line of columns along the platform, to witness ceremonial sacrifices in thanks to the gods.

The Triumphal Arch of Caracalla from 3rd century Djémila nobly frames the imposing Severus temple and Forum. To the right, up the hill, the future expansion of the town will climb. This is a relatively flat section, but Djémila is considered a premier example of how Roman grid design was adapted to such uneven terrain.

We finished our tour at the lower end of the city with the original forum and marketplaces of early 1st and 2nd century Djémila. This section was still used after the expansion uphill as a place of judgment for disputes as well as a prison.

In the marketplace of Djémila, this well-preserved tablet – with images of bull, sheep, and chicken – graphically announced the location of the butchery. No vegetarians allowed.

Timgad, founded by Trajan as a military colony in the high plains of the Aures Mountains, is considered one of the best preserved showcases for the Roman grid pattern. Unlike Djémila’s time capsule, the densely populated Timgad seen in this overview shows how the city looked at its peak in the 5th century. Aptly, toward the back, the main roadway runs through the Arch honoring Trajan.

We could not help but gasp at the size of some column pieces which had not been restored to their original location at Timgad, as some others have. When standing at the base of temples, one can’t grasp how enormous these chunks of marble or stone are. Here we found out.

The theatre of Timgad could hold 3500 people for plays and other entertainment – and is still used. As it’s built into a hill, the top provides a broad view over the huge town’s relentless grid of villas and homes (about a half kilometer square), with Trajan’s arch in the midst. Just to the side of the theatre was a famous regional library, though its remnants today don’t reveal much.

Here you see a set of market stalls at Timgad, with enough restored decoration to give an idea of what this circular indoor marketplace for goods might have looked like.

The throne room. No not for the royals, but for a wealthy family to use as a toilet. Everyone piled in together, as you can sniff out from the holes on the stone bench to the left. The more elaborate seats with armrests are clearly ritzier than the others, perhaps reserved for notables.

Tiddis

Near these settlements in the north of Algeria, one other Roman town showed us a very different adaptation to mountainous terrain. The smaller mountain settlement at Tiddis evolved from an older Numidian settlement set upon a steep hill. That required streets at odd angles (not perpendicular), stairways instead of streets, brickwork buildings partly built into rocky outcrops. And it meant a steep hike from bottom to top.

At the lower part of the hill on which Tiddis was built, we passed Numidian tombs, cave-like dwellings, and sacrificial altar sites like this one carved out of the rocky hillside.

Here we are ready to climb from those older Numidian structures to the later Roman refinements, heralded by that archway.

Museum treasures

The Cherchell museum held some fascinating treasures despite being stuck with some copies by Algiers’ museums. This representation of the Roman emperor in the first century AD was one of the best.

We were enthralled by its detailed carvings on the breastplate and the subtle flow and twist of the cloth garments. Other statues with women’s togas showed similar fine technique.

Here, Mars, god of war, hovers over the scene as Julius Caesar (in toga at the middle right) pays tribute to Venus on the left, while also being crowned, on the right, by Victory, presumably over the figures of land and sea below.

This second century marble sarcophagus, one of several at Tipaza, showed some of the wondrous sculpting technique of the period. Notice especially the overlapping legs of people and animals, as well as the depth of bodies, so cunningly carved into the stone.

The story concerns Pelops, who won the right to marry Hippodamia along with the kingdom of Olympia in a chariot race against her father, King Oenomaus. The king seated to the left, leery of a prophecy that said he would be killed by a son-in-law, had the previous candidates beheaded, as the fallen helmet to his right suggests. The preparation of the chariot horses appears on the right of the panel. Before the race, Pelops sought aid from Poseidon, who had been his lover according to some legends, and won with a winged chariot. In appreciation, he initiated the Olympic games.

We were endlessly charmed by the tombstone decorations preserved at Roman sites. This wondrous collection was displayed at Timgad. They celebrate certain personal achievements, future bounty, or hopes in the afterlife. Many also reflected the religion of northern Africans, such as the middle stone’s invocation of Astarte, the goddess of the moon. Other stones were carved with a compartmentalized serving tray at the base, where one could place offerings or delicacies for the dead.

Mosaics: The good life in stones

For centuries, in the Algerian villas of wealthy Romans, mosaic flooring was the fashion, tapestries woven not with thread but with colorful pieces of stone. Unsurprisingly, the more elaborate and subtly toned the mosaic, the showier were the results. Today, countless antique mosaics are displayed on the walls of museums across the country, well preserved beneath the sands that swept across those villas over time.

Typically, they celebrate life’s bounty or its sensual pleasures. So Venus, the goddess of love, or Bacchus/Dionysus, the gods of drink and revelry, are often central figures. The animals of sea and land abound, as merchants hoped they always would. The good life they illustrated may have faded, but the richness of its expression still lives on those walls.

(Note that the pictures can be viewed larger by clicking on them.)

Here in this large 9 x 6 meter masterpiece of subtle tile work at Setif, Venus is not the joy-bringer, but her partner in revelry, Dionysus. He’s the elaborately dressed one being crowned with victory in the chariot at the left and drawn by tigresses who are – yes – looking at you. The elaborate border alone is worth contemplating, from the helmeted, fretting old men in the corners to the centaurs in the middle defeating wild animals This processional scene was recreated many times in Roman art, as an homage apparently to Alexander the Great’s victories in Africa and India. That explains the animals and the enslaved figures chained by a Pan-like figure in the middle. More symbolically, the piece asks, are we not all enslaved to our animal nature and attended by desires? The small scene inset on the right gives the less ambiguous lesson of heroic Meleager smiting a wild boar, a defeat of our savage and beastly nature.

Detail of the central section of Setif’s Dionysus Triumphant. By our count Pan’s arm alone may have needed 12 different color tiles. And why is that elephant so irritable?

A more contemporary victory was the subject of the central image in a five-meter high mosaic from a basilica of the 2nd century AD at Tipaza. it’s a grim celebration of Roman triumphs over indigenous people.

The three figures are bound Numidian captives looking like the downtrodden of any age, while the gallery of faces in the border represent other defeated peoples – each carefully rendered, but equally downtrodden.

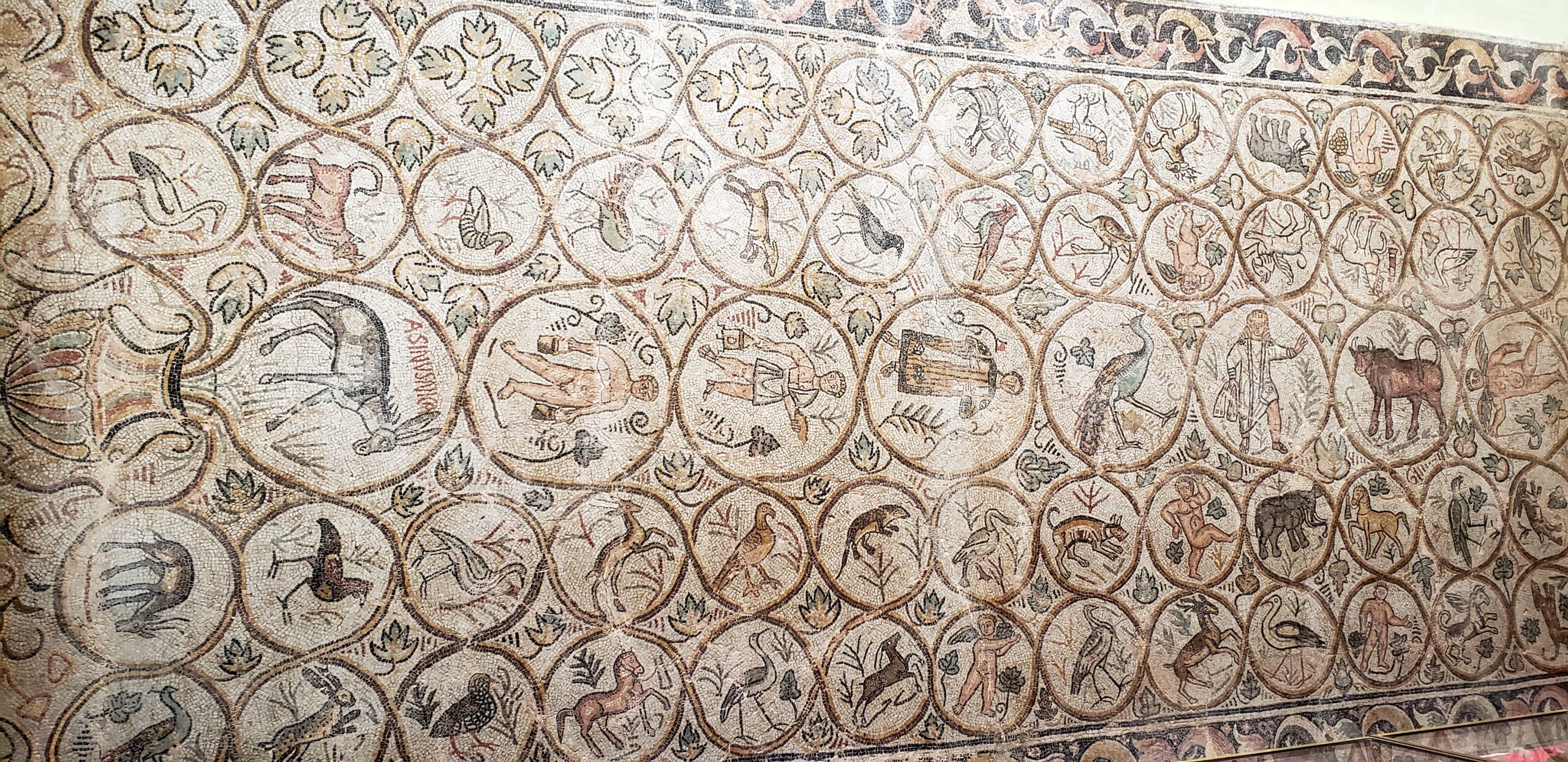

This famous 10 x 4 meter mosaic from Djemila is largely a tribute to wine, with vine tendrils weaving the myriad figures together. Many animals are placed in the circlets, domestic and wild. A few human figures also appear, notably in the middle row, which includes a central figure dressed in his best patrician outfit, presumably the owner of the villa. The oddity is the donkey to the center left, the only named figure: Asinus Nica, which means the Conquering Ass. It’s received various interpretations. Most have considered it satirical or even blasphemous, but others think it might have been the object of some game played on the tiles.

More celebration of the vine is the subject of the best mosaic we saw in Cherchell. We were entranced by the almost painterly finesse of the tilework’s color gradations, as well as by the depiction of the figures. And it was just flooring at a villa! The top half shows workers plowing and sowing the fields. The bottom half shows work in the vineyards. At the bottom left, an older man supervises. Get in close to truly savor the rich tapestry in tile.

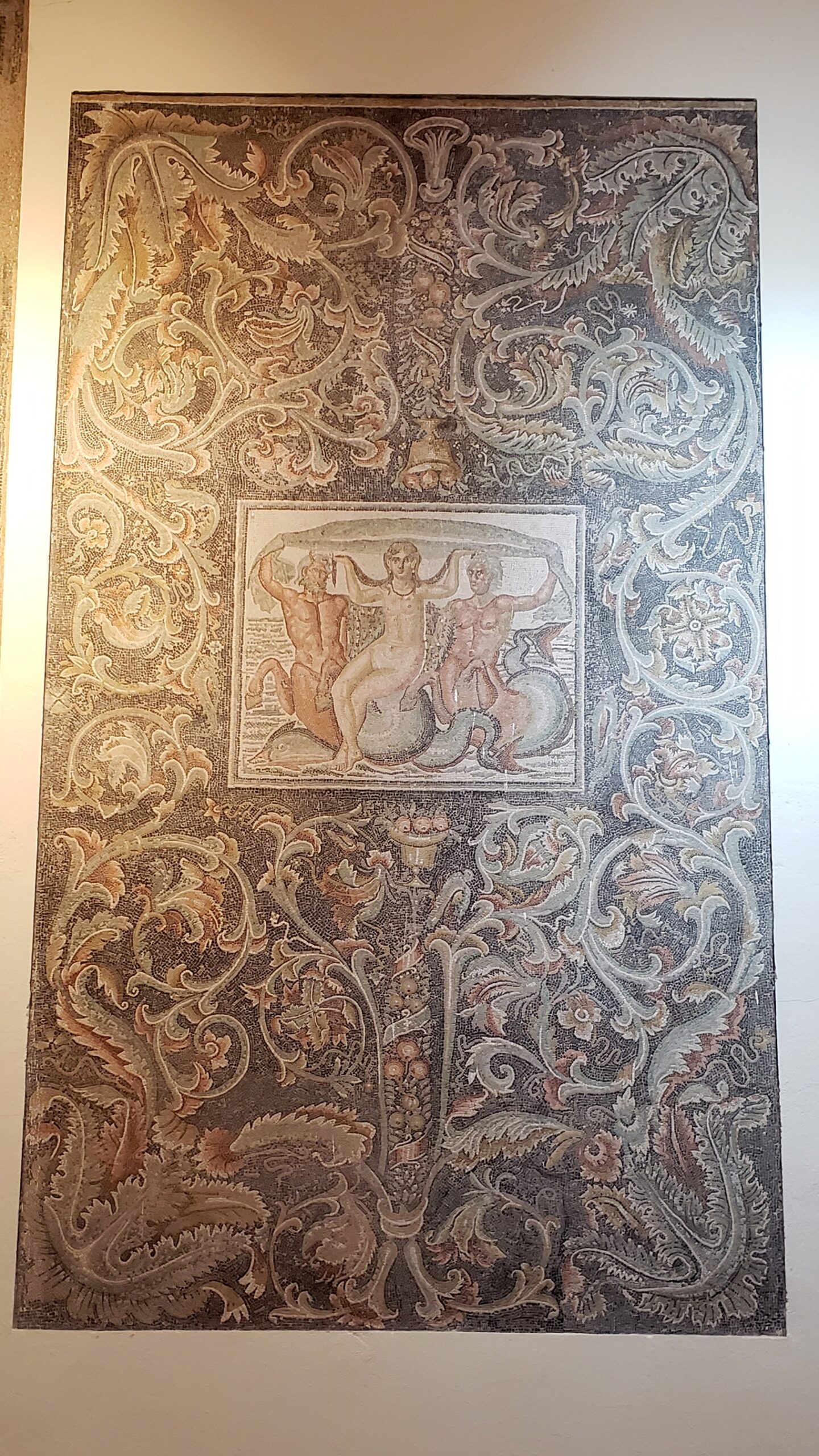

The wide border takes the prize in this mosaic from Timgad, though the center does celebrate the charms of Venus floating about with her sea-horsey concubines, all eyed by a perplexed dolphin. Snakes and birds teem within a border rich in acanthus leaves, a frequent motif since the Greeks in sculptures, building columns, and decoration. The sexualized vases rich with fruit on top and bottom draw the mind’s eye to the goddess.

The action of the mythical creatures and the detailed texture of each figure make this one of the most stunning mosaics at Timgad, yet another celebration of Venus. With good reason, however, it’s called the Sea Monsters. The tiles in this case are special also, marble and glass, in such fine gradations that the surface appears to be painted. Notice the color changes on the body of the right Nereid as well as the snarling tiger creature. This is the right half of a mosaic fragment where the figures are nearly life-sized. Venus is not present here, just these Nereids or sea-nymphs and their menagerie.

The borders of a celebration of Venus in Djemila tell the stories of lovers from classical myth in delightful detail. This part depicts the heroine, Hero, receiving her lover Leander. Though he supposedly swam across the Hellespont every night for his visit, accompanying him in the support boat are the cherubic figures of Eros as well as the strange little voyeur to Leander’s left. Fishing scenes complement the action. Such detailed work nearly made us forget we were looking at tiny bits of tile.

This is the Venus mosaic from Djemila with the border story. Though the goddess of love and sexuality was born from sea foam, here she wafts along on the half-shell, hoisted by tritons (at Djemila). She seems to be indulging a bit of vanity with that mirror she’s looking at. To her side, a couple of Nereids, or sea-goddesses, frisk with her atop mythical hybrid creatures while other sea animals frolic nearby.

A very buffed Neptune races to the hors d’oeuvres table with his fork to sample some of the fish specialties in this ocean tableau at Timgad. His favor will ensure good fishing to come..

In the later Christian era, mosaic-making continued to flourish, but with more sober treatment. As in this example from Djemila, one of many across a large wall, decoration and animals tended to be symbolic of religious virtues. These celebrated service to the one God, not the many of the Romans. Somewhat subdued crosses appear to the lower right.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Algeria, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)