We traveled far from the Mediterranean into the Great Western Erg, a vast expanse of Saharan desert in Algeria. Creamy, wind-blown sands dominate the landscape. For millennia, though, the town (Tim) of Mimoun, or Timimoun, has been a prosperous crossroads for trade across this forbidding landscape – blistering hot in summer and icy in winter.

For it’s all about the water in the desert oases, the reason people ever stopped here or created a town amidst vast stretches southward even in Algeria, as well as west into Morocco and to the rest of the Sahel. A few smaller oasis settlements can be found nearby, but you must go hundreds of kilometers away to find another desert location like Timimoun that can sustain many residents – as well as nomadic traders or tourists.

Water

You can tell from afar when you’ve arrived at water as you see the sudden effusion of greenery. Here, we are in the midst of the oasis with the desert sands sweeping the horizon. The green is the palmerei, the palm forest. Enough water below the surface also delivers surprising fertility for other crops – oranges, pomegranates, and many types of vegetables – in addition to the ubiquitous dates of the palms. Whole settlements could survive in the past on the rich nutrition of those dates as a staple. Today, a very different resource can found other settlements, industrial towns built over oil and gas reserves producing a very different kind of crop.

Natural springs at some villages can be channeled via clay pipes toward various parts of the village.This is a water distribution system for one village in the area, a method typical of desert communities across northern Africa and the middle east. A natural spring (yes, locatable by its abundant date palms) bubbles water to the surface throughout the year. The village added clay channels to direct the flow to various parts of the village.

Birds like this Great Grey Shrike and ring-necked doves know a good deal when they see it, so they too proliferate around the oasis.

Sand

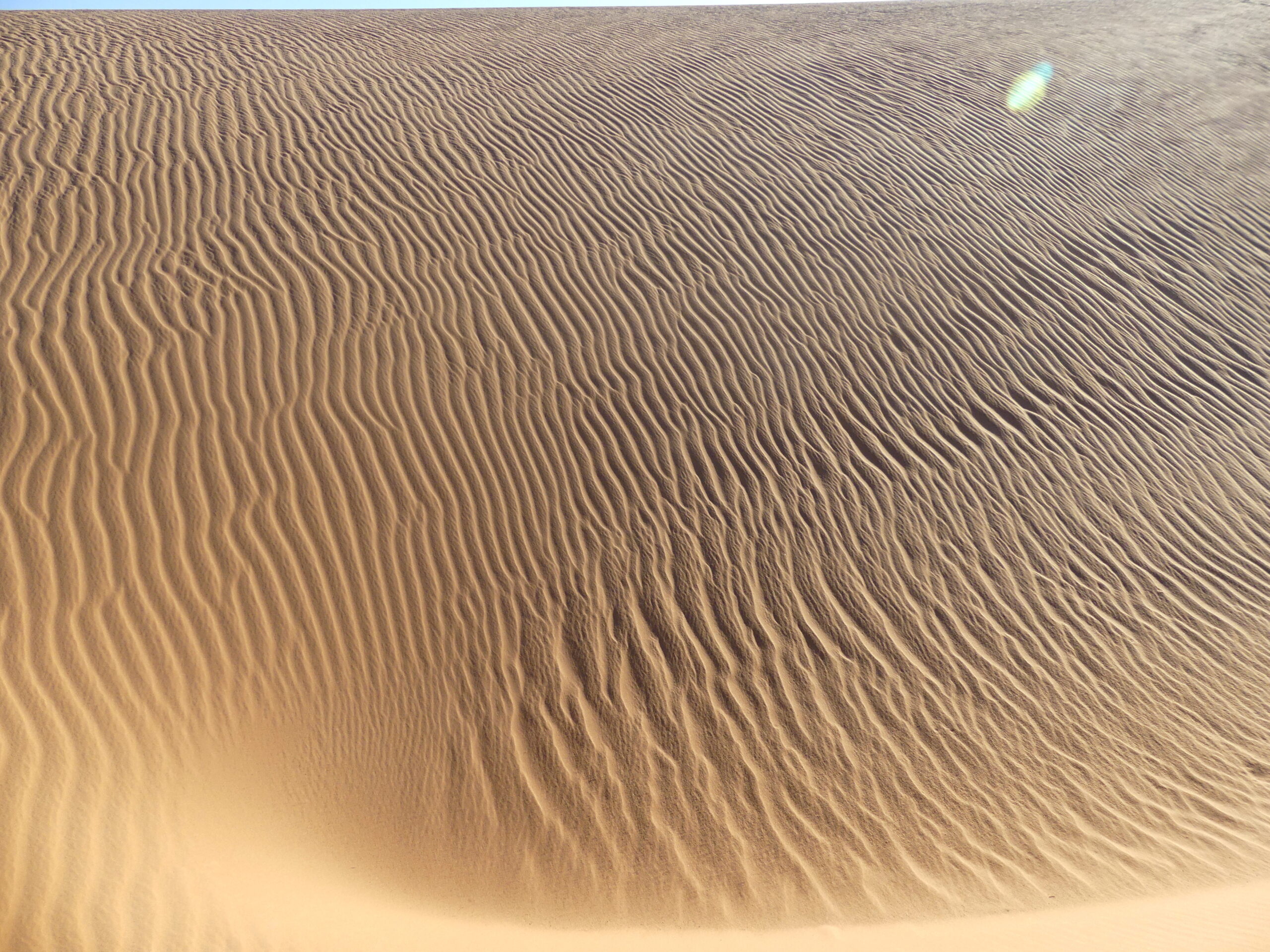

Wind forms waves of sand into swells and hollows, always shifting but, for a brief time, frozen for us in spectacular patterns.

Nancy ventures around a huge hollow in the sand of the Great Western Erg…in search of an oasis or a camel? Our Range Rover at the time was perched quite precariously, to us, at the top edge of a similar dune.

The side of one massive dune demonstrated the complex patterns in the sand generated as wind and gravity interact.

Town

In the old city, buildings crowd the narrow streets, built of a mix of red clay, straw, and palm trunks for strength (vs. the sandstone, limestone and stucco materials common to the north). We wriggled through the lanes to view the medieval mosque, the finest example of the local style to us, with its cave-like, seemingly windswept interior (reminiscent of Georgia O’Keefe’s desert imagery).

The minaret of the ancient mosque can barely be seen from the narrow lanes. But its tapered form evokes ages past: defensive turrets for perilous times, markers for mausoleums honoring village founders, and the summons for prayers offered up to heaven.

Timimoun has long featured a distinct architecture with roots in the burnt red clay around it, one apparently akin to Sudanese methods. This old city gate, now just at a junction of a side road, demonstrates the sloped-side towers and geometric decoration of the Saharan desert builders. Interestingly, the building visible through the arch on the side street, appropriately adorned with air conditioners, is currently the most evident look of the town, an adaptation by French colonial builders using stucco-covered blocks painted dark red and white. They set the newer parts of town on wide boulevards, turning their backs on the methods of the old town, with its narrow lanes to shade streets against the desert sun.

The more contemporary minaret in Ottoman octagonal style from the relatively recent history of the town.

The daily outdoor market is surprisingly robust in goods and foods, particularly considering we’re in the middle of the Saharan desert. We bought superb oranges, beans, and capsicums from this stall. A short walk away an old bearded vendor with a broad smile doled out very tasty roasted peanuts.

Our inn at Timimoun combined modern comforts with the color and feel of the nomadic or caravan tent life. Our camel…err, Range Rover…idled contentedly outside.

Beyond

An old village, founded on a rocky mound by a small oasis near Timimoun, had climbed 50 meters or so upward over time into a maze of narrow passages and rooms, all constructed of the red clay of the region. More recently, after the need for security through height waned, the villagers moved to the flatland near the oasis (close to the old mosque and founders’ mausoleum), leaving these crumbling vestiges behind.

By the 16th century, area rulers aimed to build ksars, fortified villages, in the vicinity of Timimoun as protective outposts. So, across the desert expanse, nobles and their extended families constructed residences like these atop natural hillocks, creating surprisingly elaborate arrays of rooms. Once inside, we could look out over the remains of the walls, or through crumbled gaps filling with sand, and we could hail the neighbor’s stone villa about a half kilometer away. The electric lines, which run all across the region today, illustrate how Algeria has invested in extensive infrastructure to support commercial and residential activity.

(To enlarge any picture above, click on it. Also, for more pictures from Algeria, CLICK HERE to view the slideshow at the end of the itinerary page.)